Jesse Meredith, STWMFN, 2022.

C-print, etched glass. Photo courtesy of the artist.

C-print, etched glass. Photo courtesy of the artist.

So That We May Fear Not

Review

Kelly Dolan

Emerging visual artist Jesse Meredith’s project So That We May Fear Not (2016–2022) was recently installed at two venues this past year: Finch Lane Gallery of Salt Lake City, Utah, and Basketshop Gallery of Cincinnati, Ohio. The photograph series testifies to the self-sufficiency of the individual when faced with the righteous path of patriotism, social identity, and belonging. Between the initial exhibition and its consequent re-mounting, Meredith presents documented experiences of how an individual arrives in and contends with a system of extremist or radical political ideologies within America’s far right.

The exhibition’s title piece, STWMFN (2022), sets the stage for Meredith’s photography series of militiamen and the midwestern terrain. The image depicts a man in a dirt-ridden field dressed in full camouflage fatigues laying on his side. Facing the photographer, the subject presents his body to the camera and raises his right hand to cover his face, concealing his identity. The subsequent photographs of the series invite the visitors into Meredith’s world where he documents the social nuances and relationships of the militia where like-minded individuals can hang out in the woods and train tactical maneuvers. So That We May Fear Not leads an audience to think, discuss, and feel the historical moments at present; as well as confront the taboo and intricacies of American history’s definitions of identity and belonging. Overall, the photography series documents Meredith’s observation and participation in a midwestern militia, where Meredith finds a meaningful conversation between opposing sides of selfhood. The works offer imagery, text, and materiality that resist the weaponization of these dueling ideologies and propose an alternative, more gentle approach to the high stakes position of the individual within these systems.

The notably poetic and declarative vocabulary is featured over photographs printed on various media—chromogenic prints and tactical textiles of ripstop silpoly and X-pac— and narrated directly from Meredith himself in a single-channel video. The inclusion of printed text across the photo series and closed captioning on the video incites the viewer to revisit the subject matter and imagine the artist’s alternative, non-confrontational perspective. As the words are intricately etched into the photograph’s glazing or imposed over a fabric-printed image, Meredith’s messages are simultaneously legible and illusive. His skillful placement layers the text over and casts a shadow upon the image. This produces a tendency to deliberately obscure the image’s readability or delay the message’s meaning. Many of the photographs are paired with patriotic vernacular and referential phrases: bravery, tyranny, win, lose, fear, believe, promise, among others. The text invites the viewer into the scene and welcomes larger conversations about the belief systems we as individuals hold. Moreover, Meredith begs to question what do these words and phrases hold when their context is shifted, altered, and reconsidered, especially when presented with the neutral subject matter of parked vehicles or when viewed in the gallery setting.

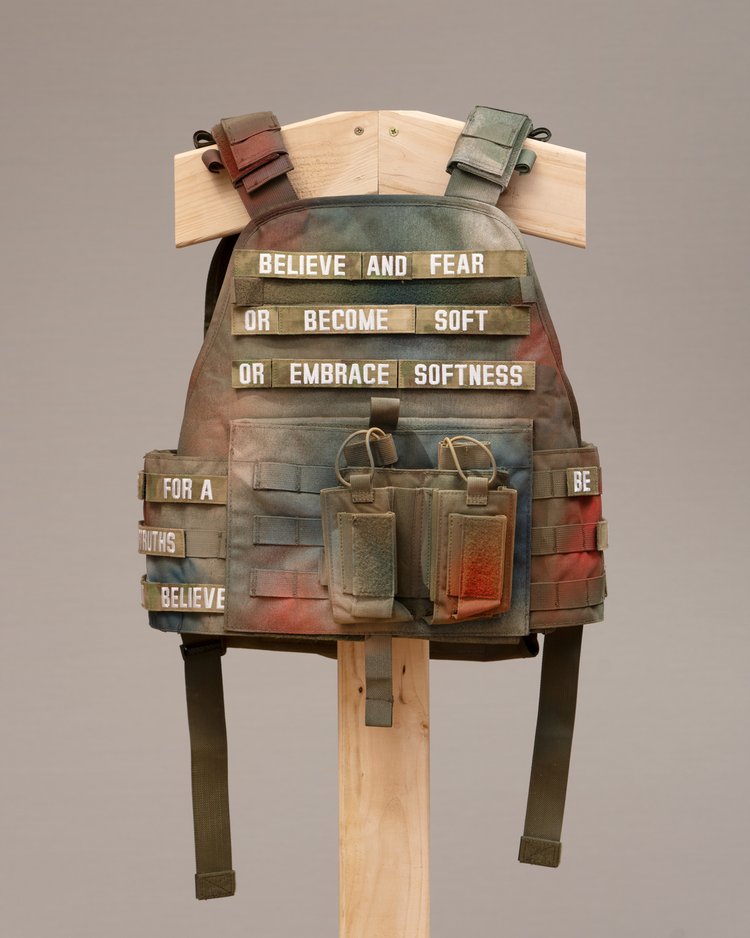

Amongst compelling imagery and contextually rich vernacular, Meredith’s installation methods lend to the utilitarian function of military equipment and lean into the softer qualities of the textile-based materials and more delicate methods of production. Coupled with framed photographs are draped curtains of tactical textiles printed with images of woods, terrain, and faceless militia members that play between the sculptural and the photographic. The works flow between the hardened, perceptively masculine subject matter and the soft material of gently sewn grommets and airy installation methods. Thematically and physically central to the exhibition is Soft Body (2022) a freestanding sculptural element of a tactical plate carrier vest hung on a gear stand made from common two-by-four lumber. Claimed as art object, the vest echoes the surrounding images of anonymous militia members wearing similar vests staged in the northern Illinois forest preserves. The sculpture lends to the project’s visual vocabulary as the surrounding images carefully weave in and out with similar visual indicators and textual phrasing. The emboldened chest reads, “BELIEVE AND FEAR / OR BECOME SOFT / OR EMBRACE SOFTNESS [sic]”. The patches read as a testament to an alternate perspective of the individual wearing such a vest. The softness, which Meredith introduces subtly and gently, implies an identity wherein the individual has a choice to follow the social construction of individualism or return to a place of compassion. And to embrace softness—the individual must begin to soften up external aggression, incendiary reactions, and the hardened lines of opposition.

A focal piece of the Finch Lane Gallery exhibition and the photograph project is Defense Mechanism (2022). Using a rigid fabric—ripstop X-pac is a performance laminate or water-resistant fabric—the work plays between the conventional two-dimensional image hung on a wall and the three-dimensional sculptural form that enters and imposes upon the viewer’s space. Here, Meredith presents living proof of drama and high-stakes situations. The image is hung by hexagonal nails and nylon rope that pulls the material taut in a compelling and effective web. Defense Mechanism is a kinetic emblem of the tension found in the image, in the text, in the material, in its title, and within the gallery space. The image shows an open area of a gravel clearing with tall grasses to the right and background. One male figure can be seen in the middle ground laying in a defensive position while another male figure in the distant background gestures with his left hand in a beckoning way to move forward and onward from this open space. The hazy text “NO URGENCY” and “NO FEAR” is immediately legible with Meredith’s use of uppercase fonts. Between the two larger-scaled, legible text reads two lines of subtext: “like the urgency of fear” and “like the fear of loss”. The additional text requires the viewer to inquire and approach the image as Meredith uses a smaller, less visible font. This dichotomy between font sizes is intentional. Meredith needs to slow the viewer down, not only to have them read and view the image but read the messages. Regardless of the message conveyed and/or received, it is within his two-fold ability to either engage the viewer upon first glance or place the burden of discovery upon the individual.

Central to the re-mounting at Basketshop Gallery is a single-channel artist video (2022 and untitled at the time of this article) not exhibited in the inaugural mounting in Salt Lake City. When entering the gallery, a distant voice can be heard yet the audio is not immediately recognizable or discernible as the voice is only carried by a small monitor’s speakers. Filmed in the vertical orientation in a 9:16 aspect ratio, the video imitates the current use of smartphones where society spends hours of their day inundated with media and also the visual field that several “at home” videos are now taken with. It begins with Meredith standing in the domestic interior—a well-lit corner of a carpeted room. He stands before the camera in jeans and a blue t-shirt, addressing the viewer directly and speaks in the second person. He chooses to speak toward the camera and break the fourth wall to address his audience at large. This is a continued effort to imitate the accessibility of similar YouTube content and the vulnerability of the individuals led into an alternate discourse they could be ill-prepared for. Within the video, Meredith echoes the vernacular from American far-right videos and adapts the vocabulary from the surrounding images of So That We May Fear Not. He begins by changing his clothing, removing the jeans and t-shirt in order to replace them with camouflage fatigues (a combat uniform), a gaiter, a bucket hat, and sunglasses.

By cloaking himself in disguise, Meredith is demonstrating how to adapt to the current environment that will inevitably surround him. He then turns his attention and actions to the room as a means to further conceal himself. He strings up various camouflage blankets and fabrics to remove the domestic interior—altering his environment in order to preserve and protect himself. The perception is that there is a sense of control within the visual changes to the individual and the environment; however, his narration reminds the viewer that this is all at the hands of paranoia and constructing an environment to meet the needs of the individual.

“You want to choose an environment that is advantageous to yourself. I’m constructing an environment that is advantageous to me, so that it appears as though I belong here, even though all I’ve done is superimpose a structure over what was already there. This way, I seem like I belong here, and I can easily see anyone who doesn’t fit in.”

-Jesse Meredith, quoted script from artist video, 2022

The artist video is a pivotal start and end to the overall project; insomuch, that Meredith has now implicated himself within the larger scope of So That We May Fear Not while simultaneously implicating the viewer. He has directly spoken to his viewers in the video, as the faceless photographer and author of the surrounding photographs. And although there are unanswered questions about audience engagement and participation across Meredith’s previous projects of the last decade, he has now delivered a face-to-face message to his viewership—connecting himself to the project, to the photographed subjects, to the narrative, and to the audience.

After building an environment of protective camouflage, Meredith completes the video by wrapping himself in camouflage blankets, completely covering himself and becoming one with the very environment and structure he has built. Meredith cleverly shifts the script from innuendos about plausible deniability, perception, and protection to self-assuring mantras of worth, value, and love. Under the material veil of perceived protection, Meredith produces an assumption that the viewer is here because they wanted to be here. Similar to the surrounding exhibition’s didactic images of militiamen and their constructed environment of protection, Meredith presents a truth that cannot be concealed: the viewing of this video cannot be undone and the message brings forth a knowledge that the viewer cannot unhave or return.

The artist video is conceptually and personally totemic in that it demonstrates just how low the barrier to entry into a world of extremist beliefs can be. It is within the accessibility of messages and content like this video that individuals can quickly garner a trove of fabricated or deniable knowledge. Herein the artist is present, Meredith has bridged the gap between the photographed subjects of So That We May Fear Not and has introduced his implied involvement in joining and documenting them. He takes the vocabulary he has heard for years—in person, online, in the media—and makes his own script of innuendos and double entendres. Meredith has taken the initiative to critique the socio-political terrain individuals are forced to navigate. So That We May Fear Not produces the instinct to analyze a photographed subject and incites resistance as looking becomes precipitated on receiving a message. In varied ways, the photographs and overlaid text are negotiations with the physical reality of some and the option to question that reality.

Within So That We May Fear Not, Jesse Meredith skillfully couples text and image as a means to weigh up and attentively gauge the subject and message simultaneously. Between the years of observing and participating in a Midwest militia or researching the social and architectural constructions of power and safety, Meredith’s projects investigate the nuances of individualism. And most notably, when these constructions are deeply rooted in the white-dominated narrative of American history and the virulent pursuit of strength and power. To engage critically and inquire about who we are as individuals in a larger system, Meredith documents his experiences and surrounding environments in order to invite shifting opinions and ideologies. So That We May Fear Not has presented an opportunity to consider our surrounding environments, learn and collaborate, and strive toward a more inclusive and full-picture historical narrative.

Installation view of So That We May Fear Not, Basketshop Gallery, Cincinnati, OH. Photo credit Fiona Schade.

Installation view of So That We May Fear Not, Basketshop Gallery, Cincinnati, OH. Photo credit Fiona Schade. Jesse Meredith, Soft Body, 2022.

Jesse Meredith, Soft Body, 2022. Plate carrier, embroidered patches, velcro, spray paint. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Installation view of So That We May Fear Not, Basketshop Gallery, Cincinnati, OH. Photo credit Fiona Schade.

Installation view of So That We May Fear Not, Basketshop Gallery, Cincinnati, OH. Photo credit Fiona Schade. Jesse Meredith, Defense Mechanism, 2022.

Jesse Meredith, Defense Mechanism, 2022. Ripstop X-Pac, grommets, paracord, masonry nails. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Video still, Artist video (from So That We May Fear Not), single channel video, running time 07:38. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Video still, Artist video (from So That We May Fear Not), single channel video, running time 07:38. Photo courtesy of the artist.Notes:

-

9.17.22

Kelly M. Dolan is a visual arts consultant, project manager, and freelance writer living and working in Chicago, IL. They hold their Master’s of Arts in Art History from the School of the Art Institute and have continuously studied LGBTQI+ & BIPOC artists who challenge traditions of making. Kelly’s recent writings follow the incorporation of unconventional and found materials from artists’ individual and cultural histories as a means for personal documentation and social commentary. www.kellymdolan.com

-

9.17.22

Kelly M. Dolan is a visual arts consultant, project manager, and freelance writer living and working in Chicago, IL. They hold their Master’s of Arts in Art History from the School of the Art Institute and have continuously studied LGBTQI+ & BIPOC artists who challenge traditions of making. Kelly’s recent writings follow the incorporation of unconventional and found materials from artists’ individual and cultural histories as a means for personal documentation and social commentary. www.kellymdolan.com