A Counterfeit Gift Wrapped in Fire

︎ Kavi Gupta Gallery, ChicagoReview

Themal Ellawala

What does it mean to inhabit a fantasy? Fantasy exists all around us, seducing us with possibilities unknown, worlds alluringly unimaginable. Despite its ubiquity, fantasy often figures in a singular manner in our imaginations. It is often the endpoint, the full stop to our musings and reveries. We dream of achieving the fantasy, but not of living it daily. We can conceive of its tantalizing surrealism, but often in a flat and elegant simplicity that collapses its complexity. Indeed, it is the very transcendent nature of fantasy that prevents us from seeing beyond the ideal, to excavate the contradictions and ambivalences that mark this phenomenon.

Devan Shimoyama’s A Counterfeit Gift Wrapped in Fire, currently on view at Chicago’s Kavi Gupta Gallery, intervenes precisely at this point, to expand into fantasy and explore its contours, its many textures and limits. Composed of paintings, sculpture, and prints of digital images (e.g., manga, Hollywood film) that span a range of subjects, this exhibition is narrated as a commentary on metamorphosis. The works all depict suspended moments of transformation, be it of the artist transitioning into a hybrid butterfly creature or his drag impersonations of Patti LaBelle. What lies unexplored in the exhibition commentary, however, is that these works depict a specific kind of metamorphosis, the transformation of the banal into the surreal. In representing a range of fantastic becomings, Shimoyama is able to conduct an archeology of fantasy, excavating its ubiquitous and effervescent nature.

It would be easy, upon seeing the shimmer and shine of these works, to be swept away by the enticements of the fantasy, much like we are in our daily existence. Everywhere lies glitter, rhinestones, jewelry, sequins, and fabric, burnishing these works with a manifest otherworldly quality. Beneath the extravagance, however, lies great depth and nuance. While at first glance one’s vision is overwhelmed by the lurid, brilliant hues of these works, a careful engagement reveals moments of quiet loveliness, such as in the graceful arch of a hand or the caress of fingers sweeping hair aside. Such moments offer a gentle counterpoint to the flamboyance of the art, a respite for the overwhelmed viewer who, dwelling on such gentleness, is compelled to stay with the fantasy and attend to its detail.

While we see Shimoyama’s subjects suspended in varying stages of transformation, his artistic process further illuminates to me what this process of becoming looks like. These works are a dazzling assemblage of media—oil, acrylic, colored pencil, glitter, sequins, silk flowers, jewelry, rhinestones, and fabric. This list demonstrates how the fantasy is constituted by banal, everyday materials that are transformed in the very process that transforms the composite whole into a phantasm, a dream. Artificial flowers morph from a lackluster imitation of nature into wondrous, otherworldly foliage. Too-big jewelry that I expect to see dripping off earlobes and necks of aunties at weddings has mutated into the enigmatic eyes of awesome beings, from embellishments-as-organs to organs-as-embellishments. Shimoyama has mentioned how the use of readymade materials features centrally in his practice, and he shops voraciously so as to have a collection to choose from as he develops each work. Becoming fantasy is a haphazard process of discovering, calculating, discarding, suturing, and repurposing the quotidian into a mesmerizing collage of bizarre brilliance. The end result is heterogeneous, messy, and uneven, not always the polished refinement we expect. Shimoyama’s process and its end results remind me that bricolage can produce some of the most potent and powerful fantasies.

Proof of Shimoyama’s complex treatment of fantasy lies in how his work offers a way to think of anti-Black structural racism as a constellation of fantasies. Take for instance the lips on all the figures. There they lie, enlarged, glistening, voluptuous. Their proportions unaligned with the rest of the figure, splayed out across the face, lying askance. These lips index the racist preoccupation with Black lips, a bodily marker that is seized by white supremacy as evidence of hypersexuality, animality, and ugliness. Desire and disgust, each forming the inner lining of the other, course through the capillaries of normative aesthetic evaluation, deeming the Black figure beautifully/horrifically non-human. It is abundantly clear that the lips on these figures do not belong to them, that they are someone else’s lips superimposed onto another, much like anti-Blackness negates the individuality of the Black subject by narrating them as an assemblage of fantastical projections. Fantasy, as Shimoyama’s lips tell us, is not only about the imaginative freedom of the minoritarian subject. Fantasy is a realm claimed by all, including dominant culture in its anxious quest for total control.

While anti-Black phantasms swirl around these lips, Shimoyama’s representations are too nuanced to be limited to them. Instead, these lips also attest to how the very symbols of racism can be resignified to represent a different, more pleasurable fantasy for Black people. His careful treatment of lips highlights their softness, their tender and sensual curves. Glossy, moisturized skin (no peeling here!) displays the care one shows towards that which is most fetishized/reviled by dominant culture. These lips lie in an intimate, if haphazard relation with the rest of the subject, and other elements of fantasy Shimoyama builds into his art, gesturing to a fundamental ambiguity of fantasy – the reveries of the Black figure occur in response to, and so marked but never fully determined by, the prejudice and violence of dominant culture.

The ambivalence of fantasy does not arise solely out of its movement between the minoritarian subject and dominant culture. Shimoyama’s figures depict a certain ambivalence about the transformations they are undergoing. The expressions they bear are hardly beatific, which one would expect in the morphing into a butterfly or celebrity. Instead, their expressions are enigmatic, veiled. It is impossible to discern how the subject feels about their metamorphosis, for neither elation nor terror can be easily read on their faces. Their eyes are especially inscrutable. Gorgeously bejeweled, these features remain the most prominent three-dimensional element to the paintings, protruding out and marking the clearest indication of transformation into the fantastical. These appliquéd eyes render the subject inaccessible to the viewer, as dependent as we are on the optical to establish recognition, understanding, and relations with one another (an argument that curiously manifests in defense of burqa bans, such as in France). If we come to understand ourselves through encountering others, then I can only wonder if these figures, inaccessible to the world, are accessible to themselves. As these figures transform from one kind of being to that of an entirely different nature, we are left wondering – does the transformed being bear an inner world? Self-awareness? Does a fantasy exist sans an audience that recognizes it, hails it, desires it? Instead of answers to these questions, we are offered profoundly ambivalent, blank expressions.

Tempérance (2022) offers insight into the unfathomability of fantasy. It depicts the artist as a blue-hued winged creature crouching by a shimmering river of blue glitter. Standing before this work, I recalled Lorna Simpson’s Waterbearer (1986). Black Studies scholar Kevin Quashie (The Sovereignty of Quiet, 2012) helps us discern in Simpson’s iconic photograph the interiority of the solitary Black figure, symbolized most potently by her orientation away from the viewer. In contrast, Shimoyama’s fantastical self-representation faces the audience, yet we are no closer to understanding him as we are Simpson’s subject. If Tempérance frustrates the expected relationship between the subject and viewer (easy access), this inaccess is compounded by Shimoyama’s rendering of this figure in a flat blue that depicts an almost-emptiness. Is this an opacity that vexes our easy understanding of the fantastical being, and deceives us into seeing only emptiness where abundance exists? Or does the translucent sheen of this subject forestall such a reading, gesturing instead to a nothingness that is the inner life of the fantasy? Is it the nothingness, the non-being of fantasy we crave?

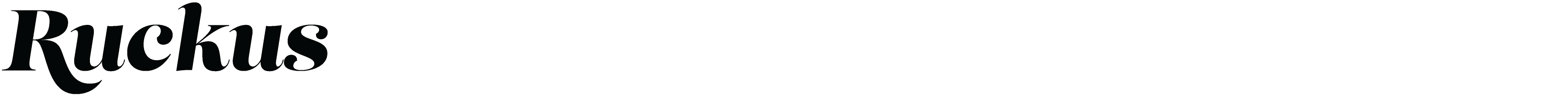

Perhaps the ambivalence towards fantasy, of both the transforming self and onlookers, arises out of a paradox, that of fantasy being both captivating and distancing at once. Take for instance Shimoyama’s commentary on celebrity. Be it the sly placement of Rihanna’s hand in La Mort (2022) or the self-portrait series that depict the artist’s drag transformations into Ronnie Spector, Lisa “Left Eye” Lopes, Aaliyah, Coi Leray, and Patti LaBelle, these works reference the celebrity of well-known artists, particularly Black women. Despite the ways in which social media has augmented the genre of tabloids and rumor that promise access into the inner sanctum of celebrity existence, the enduring fame of many of these artists lies precisely in their delicate negotiation of access and inaccess. There is no such thing as knowing the fantasy fully, for in the process it becomes demystified, and a fantasy no more. Fantasy survives on the tension between the familiar and the foreign. As much as this dialectic shapes the celebrity’s relationship with an audience, these works invite us to consider if the same can be said for the star’s relationship with themselves.

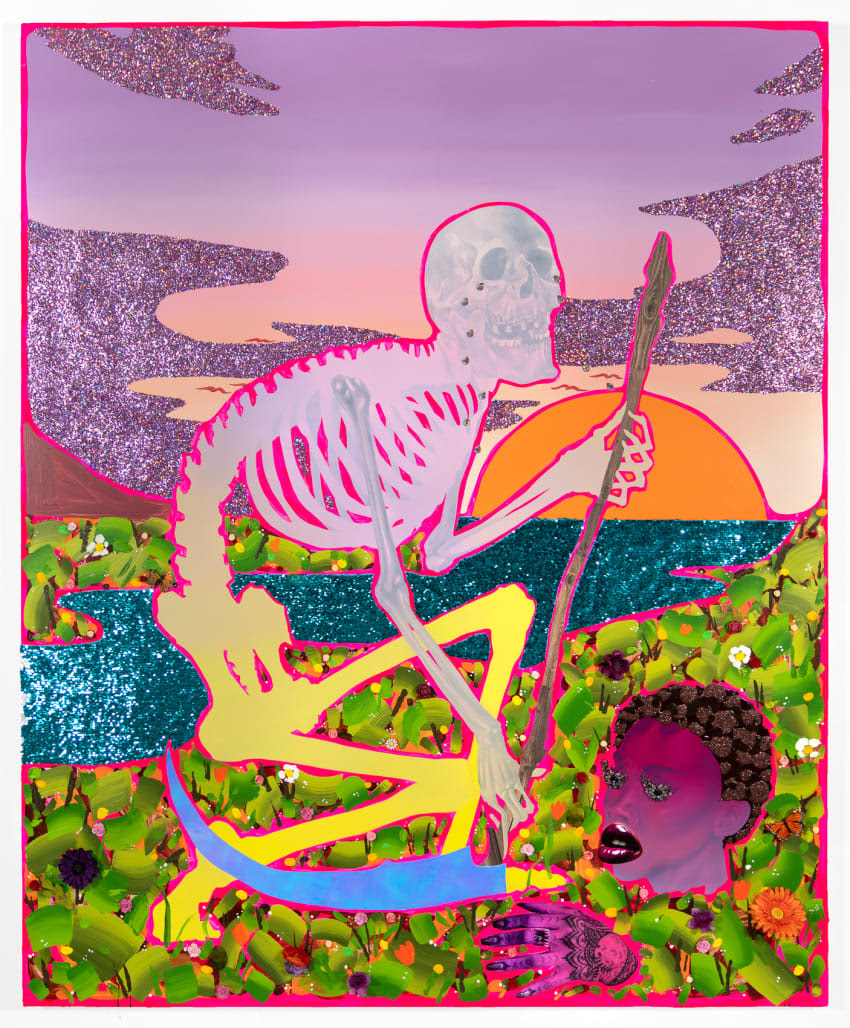

Offering a different commentary on celebrity is the snake-haired being who is the subject of Sustheno (2022). Rendered in hues of red, orange, and yellow, this character is meant to reference Stheno, the eldest of the three Gorgon sisters of Greek mythology. The exhibition notes that Stheno was the most murderous of them all. Despite this brutal mien and her immortality, Stheno has been eclipsed by her mortal sister Medusa, thanks to the fame of the Perseus myth. In Susthenso we find a subject burdened by an eternity of non-entity, resigned to a lifetime of insignificance. The fantasy of eternal life—so seductive to the human facing their own mortality in a world that cruelly depends on the artificial manufacture of death—may not offer the salve we seek, she says.

Immortality figures in other ways in this exhibition, such as in Cloud Break (2022), a hanging sculpture consisting of several boots suspended from a wire. Many of the boots are highly decorated with silver and polychromatic glitter, and some stuffed with lush bouquets of artificial flowers. Reminiscent of Barthélémy Toguo’s Strange Fruit (2017), this installation continues the conversation Shimoyama began with his 2019 work Untitled (For Tamir) and reflects on the work of memorialization. Pertinent here is how the memorialized, at times martyred, subject takes on fantastical proportions in the collective imagination. Several victims of the most publicized cases of police brutality (e.g., George Floyd, Sandra Bland, Breonna Taylor, Michael Brown) have been exalted by movements to end the state-sanctioned killing of Black, and all, people. Their names have gained a palpable presence in these collectivities, falling off lips and enshrined in prayer in a repetition that conjures a fantasy of immortality, of grace beyond the confines of an anti-Black world, of a beacon of light for those who survive them. By including this work in the exhibition, Shimoyama invites us to stretch our conception of the fantastic to comprehend its many permutations. Even as we comprehend the fantasy of these martyrs, we may ask what it means to live within them. How may the specificities and fallibilities of these figures fall away before the larger-than-life nature of their immortality? Shimoyama returns me to ambivalence, to consider how fantasy is rarely only that which glitters and glimmers, but also that which frustrates, contradicts, elides, and mystifies.

The contemporary moment is witnessing a veritable explosion in fantastical genres, from the ubiquity of Afrofuturist conversations to the renewed interest in the surrealist imaginings of the Chicago Imagists and recent exhibitions of the Black fantastic featuring Ellen Gallagher, Hew Locke, Chris Ofili, and Kara Walker. As we face the collapse of neoliberal society, the ever-widening spread of fascism, sustained pandemic life, and planetary extinction, we turn to fantasy for a reprieve from slow and brash violence, to dream our way into a different world. Devan Shimoyama’s work confirms the necessity of fantasy for such projects while cautioning us against embracing it as the singular solution to the malaise of our times. Fantasy is tinged with ambiguity, transformation inflected with uncertainty, suggesting we tread cautiously on the path towards an alternative, fantastical world.

-

6.6.22

"Themal Ellawala (he/they) writes, thinks, dreams (but doesn’t get enough sleep), talks (too much), listens (deeply), and cares for a world suspended in silences, ambiguities, and absences. Their work, in the academy and the arts, seeks to approach the glimmers of such a world, and the ways to inhabit it so that the contradictions of life become bearable, beautiful"

Devan Shimoyama, Tempérance, 2022, courtesy of Kavi Gupta.

Devan Shimoyama, Winning Love by Daylight, 2022, courtesy of Kavi Gupta

Devan Shimoyama, La Mort, 2022, courtesy of Kavi Gupta

Devan Shimoyama, Sustheno, 2022, courtesy of Kavi Gupta

Devan Shimoyama, Self Portrait as Patti, 2022, courtesy of Kavi Gupta