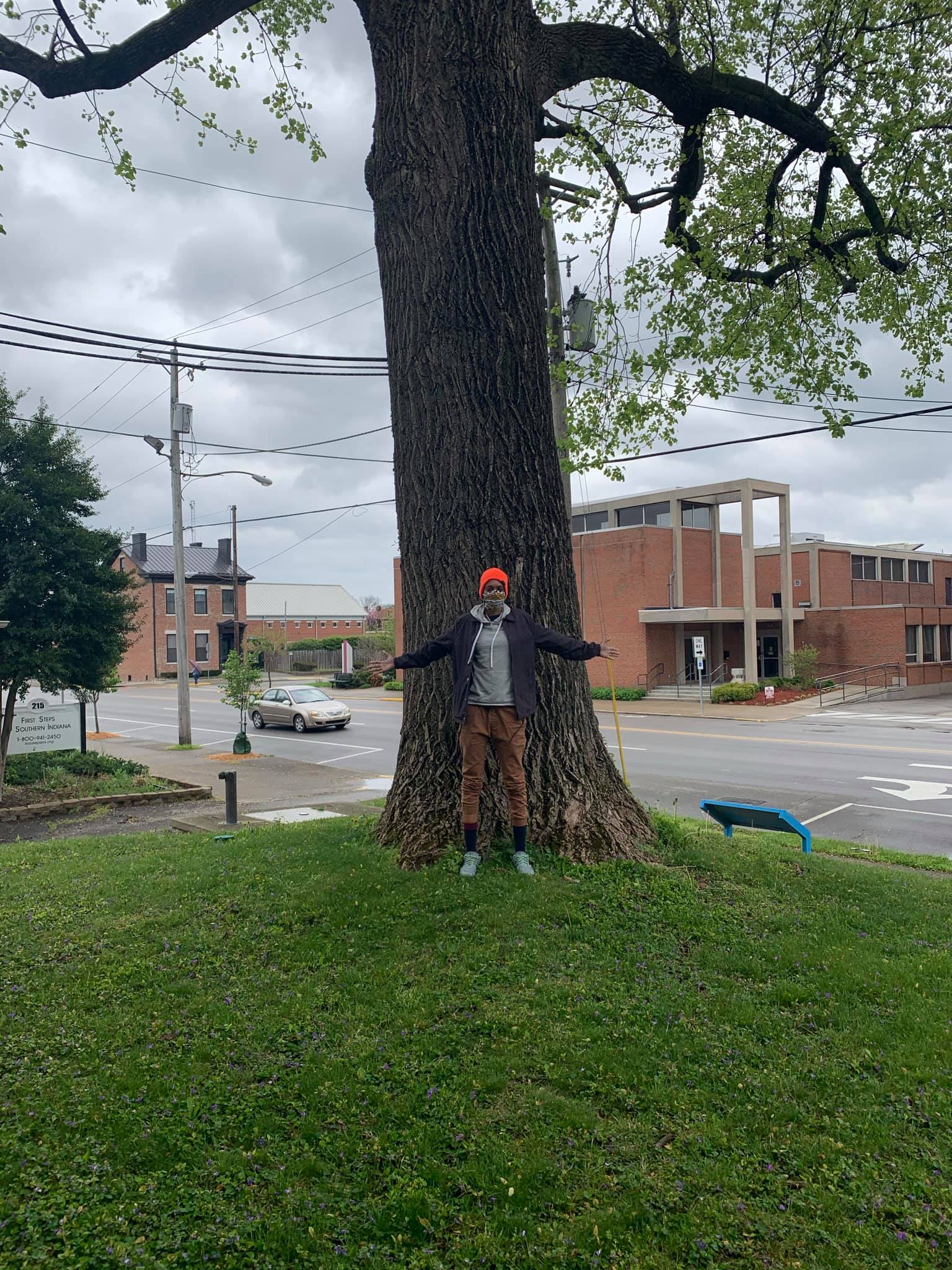

Above: Alexis STIX Brown

Alexis STIX Brown

Q&A

with Jessica Oberdick

Alexis STIX Brown is a visual artist from Radcliffe, KY. She received her BFA from Bellarmine University in 2006 and is currently working as the first Artist in Residence at the Carnegie Center for Art and History in New Albany, IN. I sat down with Alexis in her space at the Carnegie Center to learn more about her goals for the residency and her work with the community.

Jessica Oberdick: Can you tell me how you became an artist?

Alexis STIX Brown: My dad encouraged my art. My mom’s mom was an artist and when I started drawing, my dad really encouraged it. He worked at a publisher’s printing company and they would print all these horse books; whatever books weren’t good enough to resell, he would bring them home to me. So I would always try to draw horses and he would bring me computer paper and, to this day, I have an infatuation with computer paper. It’s infinite, the possibilities are endless.

When I was in high school, art was taken out of the school system which was really challenging for me. And sports were really being pushed on me, so I became a basketball player even though I am really not a sports fan, I’m just tall. But it had its good moments and it paid for me to go to Bellarmine University on a full scholarship. At Bellarmine, I was able to get back into the art department and I got to study under some amazing teachers. It was my senior year that I decided I would never give up on art.

JO: How did your art style develop?

ASB: I've always been interpreting my personal life and my journey into my work and it just began to evolve over time. When I moved to Florida, I started dealing with a lot of anxiety and that's when the line work came in that bolstered my illustrations. And once COVID hit, I was having this spiritual warfare type thing going on and was really trying to identify who I am. And it started stamping out what I had been drawing, what I've been accumulating since high school. Then I get this opportunity at the Carnegie Center to just share everything from the beginning.

JO: How did you get involved with the Carnegie Center?

ASB: The biggest thing was Jinnifer (Jinn Bug is a visual artist and poet based in Clarksville). She saw me going through it in Florida and just wanted to help however she could, which ended up with me being able to take residence in Clarksville. She had it planned that we would come here and do a Zoom class for embroidery stitching for kids and I would be her intern. The staff decided not to do the activity due to COVID, and they were looking for something more local. And then she (Jinn) helped me write the proposal that was accepted to do this residency. By allowing me to be her apprentice for an art activity at the Carnegie, I was placed in plain view of decision makers who have taken a liking to my art.

I have a private group on Facebook. It is called The Interlocutor, which Julie (Leidner) named. In The Interlocutor, I document exactly how this residency came to be and the emotions that I experienced from the first three days of working here, which was really intense. And I did that because it is so easy to lose the community that helped you get here. There were a lot of people that did a lot of back bending things for me to have an opportunity like this.

JO: What was your original plan coming in here?

ASB: I’m proud to say that we’re sticking to our original proposal. The baseline is to address anxiety with lines and for the lines to represent lines of communication through intergenerational conversations, where older people are talking to younger people, younger people are talking to even younger people and creating a community, a place for people with good intentions to make memories. I’ve been hashtagging #CarnegieMemories lately: that’s a whole vibe.

But (in the proposal) we wanted to work with outside artists, and the first one is Ramona Lindsey. She is a multimedia textile artist out of Louisville. Her kids are actually amazing artists themselves and their dynamic is very interesting as mother and children creating.

So, when we talk about intergenerational conversations, we're also trying to address community engagement. What can people come out and participate in? I have made some of my artwork to where people could touch it, or we can talk about it as interactive. With Ramona's piece, outside, there's a poplar tree and we have built an armature around it. The tree is going to have green wombs where we pack dirt inside of these packets and the community is going to come in and plant seeds inside of the dirt pouches, and in about 90 days they will be blooming marigolds. So the skirt for the tree will be a living communal engagement.

JO What has the community feedback been like?

ASB :You know… I'm living in a world where I feel like the world is a blaze and then I come outside and everybody's normal and it's such a complex spot for me. Now that there's so much information in the world, you don't know what frequency anybody is on. So I was freaked out to be in here. But the most amazing people in the community meet me here. I'm very excited with the type of people that the Carnegie Center attracts. And I think that they attract people who are interested in education because they're a branch of the library and I see how the education of the library presses into the arts. It's what I've always wanted.

JO: On the Carnegie Center website, you talk about community and how you want this residency to be a safe space. This reminded me of an interview I heard on NPR with poet Tess Taylor where she was talking about how art is used in Ireland to create places of healing. How do you see the role of art as a tool in bringing the community together?

ASB: What's going through my mind when you asked me this is why they ever pulled art out of schools. They had to know that there's a synergy there, but people have to go to work and to go to work, you gotta kill those dreams. But art makes you dream, you know? There is a synergy that's happening right now. And if we don't protect it, if we don't honor it, if we go the other way that keeps tempting me, that keeps tempting all of Louisville, we're going to keep missing it. I think that people are ready to heal but we haven't had people in positions of power to protect that space. And that's why I speak so highly about Julie, because I've never experienced such protection in a place before and using whatever resources she has access to, to make sure that we have everything we need to make this successful. It's very rare for me to be in an environment where things actually work.

JO: What are your biggest challenges you have had during this residency?

ASB: My biggest challenge is myself. I had to realize that I had to take responsibility for the decisions that I make. I’ve been trying to do that all my life. I always felt like if this would've happened, this wouldn't have happened and that's not fair because none of it has to do with my personal control. So I think I'm battling myself and understanding balance.

Luckily, I've had that support where everybody's like, oh, do whatever you want, and really want me to be free. So, I think the lift off for me is going to be learning how to be this type of free for myself, without looking for other people to offer it to me.

JO: I also wanted to ask you about your Moon Script.

ASB: In high school, I came up with this alphabet to keep my mom from reading my journal. It always makes people laugh. I'm like, I'm sorry, mom, this has to be so funny. She came in the other day and was like, you never taught me how to read it, but now you're teaching the whole world.

The kids love it. Certain ages are excited they can read it. And the younger ones are excited that they can point out the letters of their name. Watching people look at it is really fun.

JO: Is there anything else you want to share?

ASB: You know, amidst all of this chaos. I would like to say that I've always aspired to be an elf. I want to make elf ears and stitch my sock monkeys and get ready for Christmas. I know it’s early to talk about Christmas, but my mother and I decided that Christmas is every day, and I always enjoy that spirit of Christmas and what people carry with them during that time. That's really what I'm hanging on to while everything else is chaos.

I think it's so easy for Black people to talk about race, but with caucasian people it's so easy to talk about anything else, let's talk about bugs, butterflies, birds, like we get race conversations. I'm really trying, and it's important. It's important if it's helpful. But a lot of times, we're just talking about it cause we're venting and it's not helping. Actually, it's to a point where it could be hurting if we're not working on other things.

I really am trying in these interviews to push conversation towards community engagement and creating safe spaces, and things that Black people don't usually have a place to speak about. And that's a reflection of my work too. That's why I purposely never really do artwork that is politically driven, because this is supposed to be my safe space. This is supposed to be where I go to create.

-

Notes:

-

7.13.21

Jessica Oberdick (she/her) is an independent curator and writer whose research focuses on themes of identity and social perception. She currently works as the Exhibitions Assistant at the University of Louisville.

Alexis STIX Brown