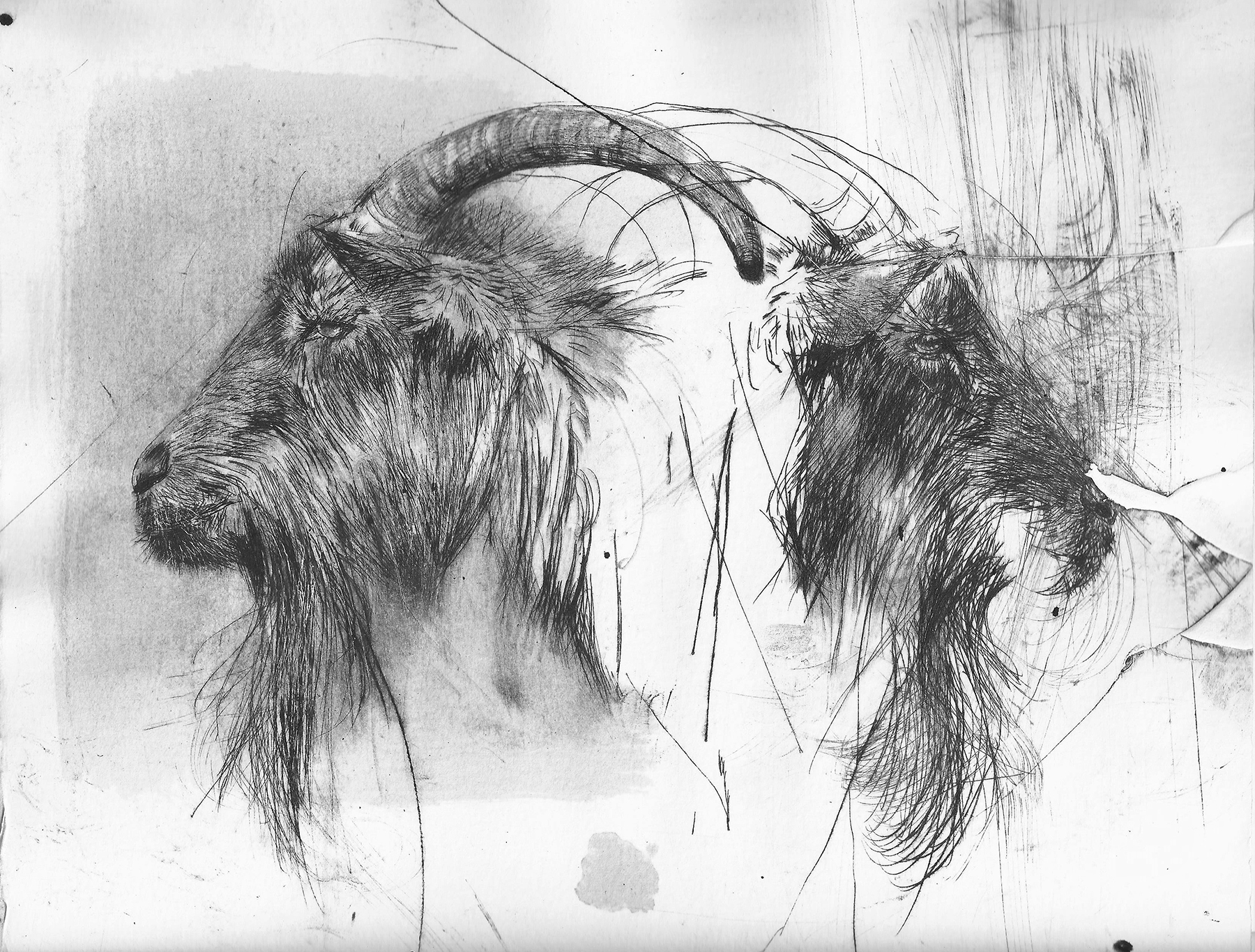

Above: Goat (2018). Intaglio etching on paper, 12”x9”. Image provided by the artist, Douglas Miller.

︎ Louisville

All The Useless Things Are Mine:

A Book of Seventeens

Review

Megan Bickel

Editors note: this piece was originally scheduled for public release in early June, 2020, however, it was postponed so that Ruckus could make room for voices related to the Black Lives Matter movement.

Here Lies Me

“I was only guilty of drunkenness once . . . only once. . .that time being the time I was alive.”

With luck, your copy of Thomas Walton’s All The Useless Things Are Mine (Sagging Meniscus Press, 2020) will fit in the back pocket of your jeans along with a pen. This is important as you may need other pockets for your wallet, mask, keys, and perhaps a snack if you venture out to read in public—circling or notating bits that resonate or instigate a giggle. On the back cover of this pocket-sized book it is announced—proclaimed even— that this is a “book of seventeen-word aphorisms and otherisms, arranged thematically to respond to various themes—politics, love and sex, parenthood, the afterlife, etc.” No big deal, just a tiny book covering the largest subjects of human experience. . . and, et cetera. Accompanying Walton’s text are seventeen drawings and etchings rendering various animals, trees, shells, and one set of human hands, all contributed by Louisville artist, educator, and observist Douglas Miller. Millers’ drawings coordinate well with Walton’s words, as both work to focus on the mundane in order to realize a larger observation about the world.

The aphorism first appeared in Greece within Hippocrates’ Aphorisms, a book of propositions concerning the symptoms and diagnosis of disease and the art of healing and medicine1. Thus, aphorisms came into being as the result of experience. They require no proof, and appertain to pure reason. For example, one doesn’t need an analytic breakdown of the common aphorism, “Actions speak louder than words.” It’s evidenced in learned experience. Aphorisms have been especially used in dealing with subjects to which no methodical or scientific treatment was applied until recently, such as art, agriculture, medicine, jurisprudence and politics. Understanding the aphorism in this context helps rationalize the literary abstractions that Walton regularly utilizes, an example being “All morning rain grey as a seal sigh misted the garden until sunlight finally burst laughing through.”2 Here, Walton anthropomorphizes both sun and rain to insinuate that a morning rain shower is inherently witty due to its trickster qualities, exemplifying that weather systems can mislead us in the same manner as a good joke.

As is the case with aphorisms, these short observations seem to be the labor of those that are overly ambitious, proven in their prolific observational skills, but with low resolution to give too much energy to any one thing. Thomas Walton’s All The Useless Things Are Mine organizes this prolificacy into twenty-six chapters with titles such as, “Landscape Paintings,” “Songs of Innocence in Milwaukee,” “Art Criticism,” “Looking Back,” and “The Afterlife.” Outside of these designations, the short haiku-like sentiments offer observation after quick observation, served as a macaroon with the emotional heft of a large slice of tiramisu—actually, never mind the slice, it’s the whole emotional cake.

In conversation with Walton’s aphorisms, Douglas Miller provided seventeen intaglio etchings and / or drawings for this collection. It’s a pleasure to indulge in momentary readings that end or convulse into viewings of lovely images that are half battled, sometimes fatigued, and always extraordinarily rendered. I sometimes balk at the idea of making picture books of adult content--they can feel half hearted and ill paired—but this partnership feels both appropriate and delightful. As Walton provides brevity, abstraction, or anthropomorphized observations regarding human experience, Miller provides the same flexibility in his stylistic renderings or portraits of animals, specifically. Exemplified in his exquisite rendering of two goat portraits, “Goat” (2018) originally scaled to 12” by 9,” has been shrunk to an approximated 3.5” by 5” and turned on its axis so that the image is then vertical. Miller’s stylistic smudging surrounding his figurative focus—the fully realized goat portrait—makes the less ‘complete’ or less rendered goat (now hovering above) abstracted in such a way that it takes some physical exploring of the book: rotating, pausing, and contemplating, to fully realize both goat portraits. In other words, Walton’s joke about a morning rain shower tricking us once the sun comes out from behind the clouds and Miller’s stylistic selection of what to include or remove from a drawing offer a synchronistic view of the world: open ended and reveling in brevity.

Fiction, poetry, and prose all afford the reader the imagined aesthetic experience—for example, please imagine piles of dahlias, marigolds, poppies, ferns, and flush moss (see . . . wasn't that nice?). But images afford something different—they offer something concrete and fully realized to contemplate, an object that already exists. Most of the cerebral work is already done. It’s rare, really rare, to be afforded the opportunity to go from one realm of imagined aesthetic experience to a realized one instantaneously. This is the case as you read and turn the sheet from page ninety-three to ninety-four. At the bottom of page ninety-three (located within the chapter titled “Quotes and Paraphrases”) rests the little aphorism “La Rochefoucauld3 says, ‘some people are like popular songs that you only sing for a short time,’” which succeeds both as a joke at the expense of a flowery and anti-romantic philosopher and as a truism itself. I turned the page to find Miller’s “Tree” (2020) standing with virility, verisimilitude, and the tiniest bit of aggression for the reader. Standing solo, the pine tree is rendered with incised digging, cross cuts, soft scratches, smears and thumb prints. Walton’s ingredients: melancholy, humor, and desire, are undercut by this tree that reminds the reader that they’re only human, and that is synchronistically everything and nothing.

-

Notes:

- 1. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Aphorism". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 165.

- 2. Walton, Thomas. “Landscape Paintings.” All The Useless Things Are Mine. A Book of Seventeens. p 9. Sagging Meniscus Press, New Jersey. 2020

- 3. (1613-80) French classical author who had been one of the most active rebels of the Fronde before he became the leading exponent of the maxime, a French literary form of epigram that expresses a harsh or paradoxical truth with brevity. Moore, Will. “François VI, duc de La Rochefoucauld.” Encyclopædia Britannica. February 10th, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Francois-VI-duke-de-La-Rochefoucauld Accessed May 13th, 2020.

- All The Useless Things Are Mine:

A Book of Seventeens

-

Megan Bickel

Contributor to Ruckus

6.1.20

Tree (2020), intaglio etching on paper, 6”x4”. Image provided by thhe artist, Douglas Miller.

Hand (2018), graphite on paper, 14”x11”. Image provided by the artist, Douglas Miller

Hand (2018), graphite on paper, 14”x11”. Image provided by the artist, Douglas Miller

Shell (2020), intaglio etching on paper, 8”x5”. Image provided by the artist, Douglas Miller.