José Manuel Nápoles Puerto

Artist Profile

Sara Olshansky

Hailing from a small town in Cuba, José Manuel Nápoles Puerto has already enriched Louisville’s art scene with a unique practice and an important perspective in the three short years he has lived here. Nápoles Puerto is currently preparing a body of work titled “11 Days, 11 Countries,” which chronicles his journey leaving Cuba, traveling through Central America, and into the United States. Throughout these eleven days, Nápoles Puerto faced the volatile terrain of eleven different countries, unpredictable authority figures, and the potential for fatal sickness or injury. Nápoles Puerto and his small group of comrades slept in fields and scavenged for food. The physical and emotional toll of this journey is palpable when viewing his work.

Nápoles Puerto’s story is one that echoes throughout the United States as a kind of American odyssey. Politicians and mainstream media regurgitate these stories while forgetting the real cost of such a feat—as they are told and retold, the real weight becomes generalized, abstracted, and often demonized. Nápoles Puerto endeavors to break open this echo chamber and to shed light on his own individuality, telling the real story of immigration in his life. His story brings with it its own origins, trials, and triumphs, not to be lumped into a package to describe what many think of as the mimic-actions of all immigrants.

Although content concerning hardship is abundant in stories like Nápoles Puerto’s, the artist does not dwell only on what is clearly difficult about his journey. Instead, the real strength behind these narratives is Nápoles Puerto’s ability to bring to life the multifaceted, psychological experience of each of the eleven days, where hardship intersects with fortune. Contrary to what conservative politicians and mainstream media have rolled out as a repeated, bleak tredge to the border in hopes of leaching from the United States’ resources, criminality and desolation are not the prevailing heroes here. Instead, juxtaposed, as they are in Nápoles Puerto’s paintings, are escape and respite, loss and comradery, fear and contentment. The paintings outline the inescapable human ability to intellectually occupy opposing feelings at once, to enjoy what you fear, to remember fondly what you wished to escape. In recounting these eleven days, Nápoles Puerto has been known to comment on the beautiful landscapes, how he’d never have been able to see them without enduring the journey. He recalls the strong friendships he forged. In his narrative paintings, we see lush landscapes, vivid colors, and figures packed closely together as if guiding one another forward in a supportive embrace.

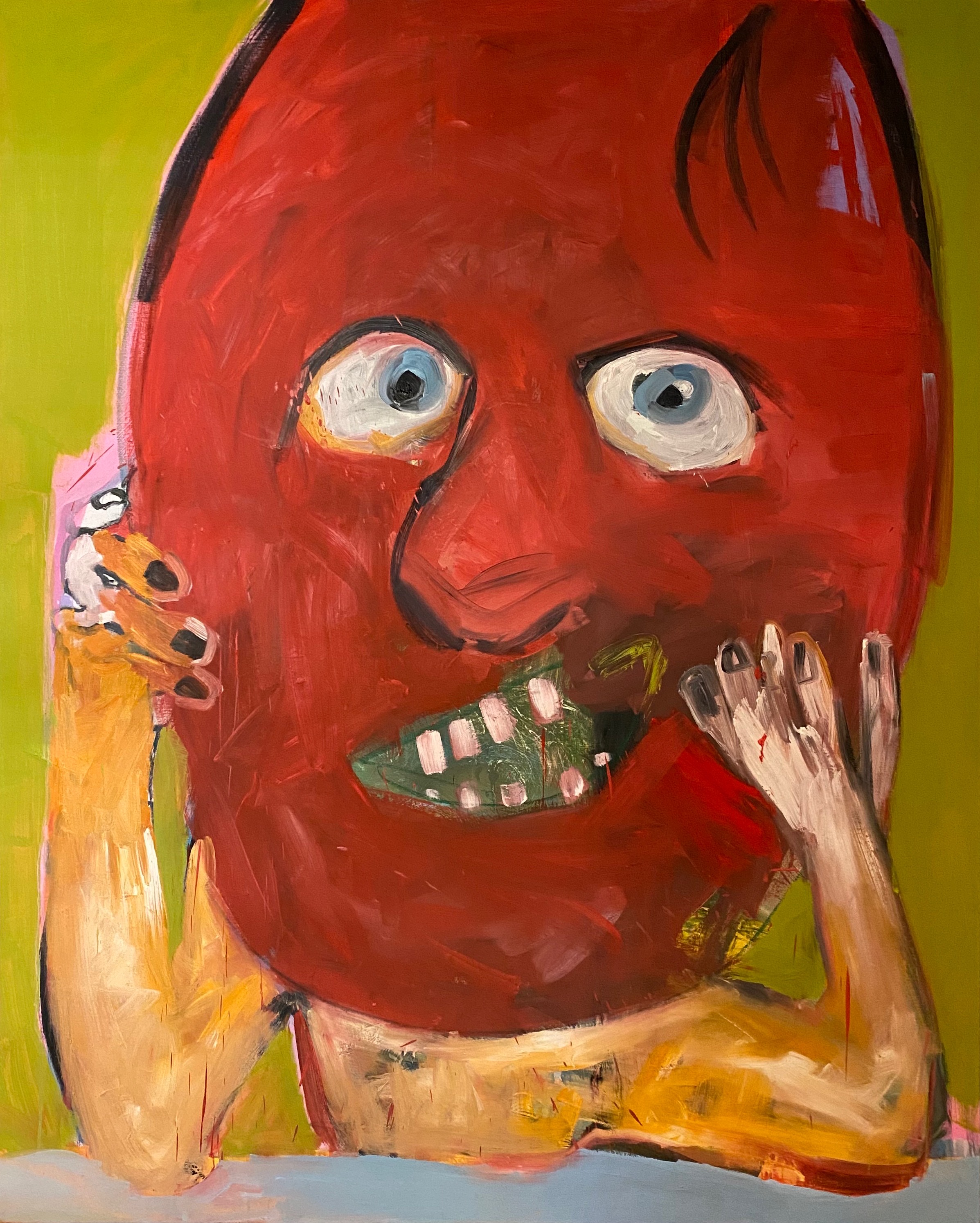

However, Nápoles Puerto’s paintings do not cast a “brightside” veneer over a tumultuous history. Rather, they offer a revision to the language we use to tell these stories, language which too often muddles and clumps, language that is generalized and weaponized, levied against entire populations of people. His work at once acknowledges and qualifies the U.S.’s preconceptions about these issues: as mainstream society spews the same story of immigration, it has reduced the narrative to a few convenient buzzwords, words that represent immigrants as criminals. Instead of patching the holes in this understanding, Nápoles Puerto’s work appropriates the fear-effect, blowing the stereotype up to a hyperbolic proportion. In a subsect of Nápoles Puerto’s series, he paints terrifying, distorted portraits in the same family of work by Dana Schultz or Francis Bacon. These portraits of monsters, reminiscent of childhood nightmares, expose the flaws in the logic of fear-mongering so often used to criminalize Latinx immigrants.

Nápoles Puerto’s practice has centered in part on this infantil, or “child-like” style. In addition to the already thought-provoking paradox of tedious development of what appears to be effortless and unskilled, a child-like aesthetic in the context of U.S. immigration creates a chasm in mainstream demonizing perceptions of immigrants, who are often feared. Within the U.S., if a child is born into difficult circumstances, our society does not attribute the flaws in their paths to the child’s behavior, character, or choices. Instead, society is likely to point to the parents, their educations, and the systems in place which have predisposed them toward their path. It’s worth noting here that this sentiment clearly hits an expiration date, a date which is earlier and, at times, non-existent for Black and Brown children. In psychology, this phenomenon is called the Fundamental Attribution Error.1 For example, in their article “Rethinking Symbolic Racism: Evidence of Attribution Bias,” Brad T. Gomez and J. Matthew Wilson state that for some, “the observed disparity between the races is a function of systemic causes, such as unequal educational and job opportunities or a legacy of discrimination (‘structuralist attributions’; Feagin 1972).” However, many “view racial disparities as a product of traits stereotypically associated with [marginalized individuals], such as a poor work ethic or a lack of intelligence (‘individualistic attributions’).”2 While white U.S. citizens are allotted “structuralist attribution” explanations to excuse their behavior in uncontrollable circumstances, the same allowances are not made in the case for immigration despite their similarities.3 People who immigrate to the U.S. are often attempting to escape a plagued environment they have been born into. The estilo infantil in Nápoles Puerto’s work makes this logical fallacy visible, refracting it back onto the viewer. We do not fault children for their born environment. The subjects in his portraits, painted as if from a child’s imagination, ask us why we fault immigrants for changing the only circumstances within their control.

Before leaving his hometown, the Cuban government censored Nápoles Puerto’s work, dismantling two exhibitions. His co-conspirators in art later installed the dismantled exhibition in the most important gallery in the city in an act of defiance. As a professor of painting and a widely exhibited artist, the Cuban government took note of his career and forced their will upon his practice. He spoke out too frequently against their institution, made work that did not align with their desired concept, and was ultimately driven out. Upon arrival in Louisville, Nápoles Puerto found more than freedom in art. The people in Cuba live under an oppressive system, standing in line for hours to get basic groceries they can barely afford.4 Now, in Louisville, Nápoles Puerto is able to meet basic needs and make work that he believes in. While his life has taken on new levels of comfort, he must still contend with the overwhelming prejudice that surrounds being a Latinx immigrant in the United States today. This series represents a celebration of his move to the United States, a critique of the system he left, and an opportunity for those who will never experience such a journey, to catch a glimpse into a real story of American immigration.

-

José Manuel Nápoles Puerto currently lives and works in Louisville, KY. He will be exhibiting work in Quappi Project’s upcoming group exhibition We All Declare Liberty on October 9th. He is represented by Moremen Gallery in downtown Louisville.

Ruckus Louisville would like to thank and credit José Manuel Nápoles Puerto and his partner, Maria Riveron Siam, for recounting their stories of living in and leaving Cuba and their ensuing journey to Louisville.

-

Cited:

- Gomez, Brad T. and J. Matthew Wilson, “Rethinking Symbolic Racism: Evidence of Attribution Bias,” The Journal of Politics, vol. 68, no. 3 (August 2006): 611-625.

- Ibid., 611.

- Ibid., 611.

- Interview with José Manuel Nápoles Puerto and Maria Riveron Siam

9.22.20

Sara Olshansky

Contributor to Ruckus

Untitled, finished in 2020, oil on canvas.

Untitled, finished in 2020, oil on canvas.

Untitled, finished in 2020, oil on canvas.

Untitled, finished in 2020, oil on canvas.

Untitled, finished in 2020, oil on canvas.

Featured in Art of Gravity, ep. 01.