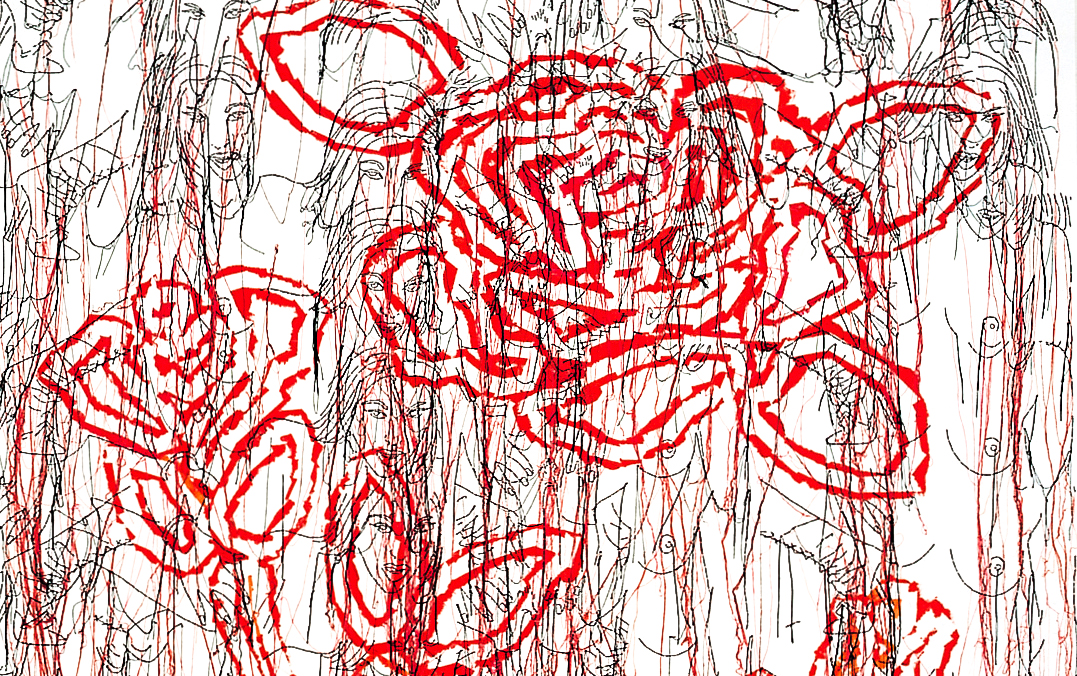

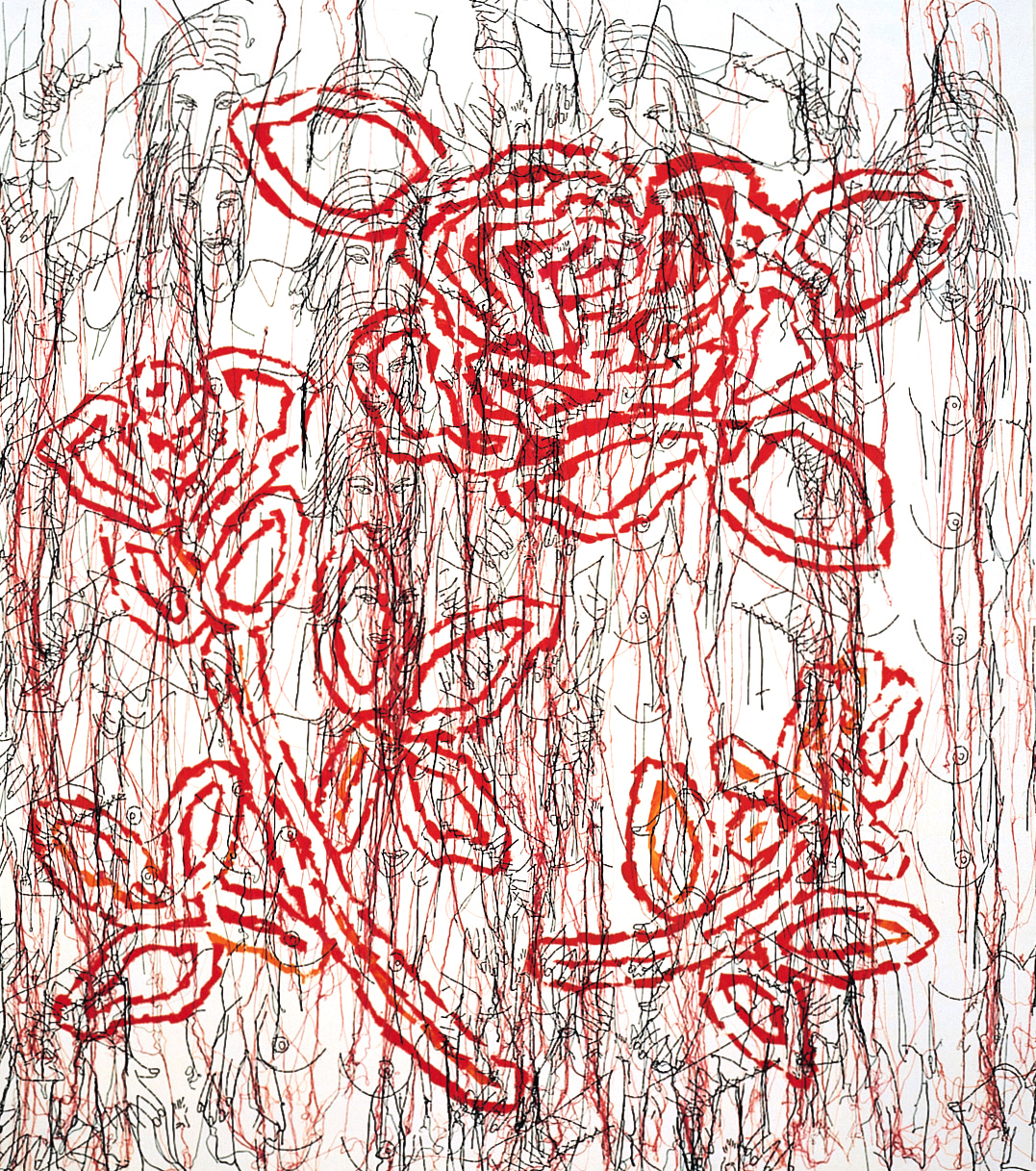

PHOTO EXCERPT: Ghada Amer, The Big Red Rose—RFGA, 2004. Image courtesy of the Speed Art Museum.

︎ Speed Art Museum, Louisville

Breaking the Mold

Breaking the Mold: Investigating Gender at the Speed Art Museum is an ambitious exhibition that brings together contemporary, modern, and even ancient art that explores diverse perspectives on gender, sexuality, and the body. With a show of this scale and breadth, it can be easy to get lost in the minutia of how individual works interact with one another. It is critical that viewers are cognizant of this web of connections, as Breaking the Mold requires that we weave threads between sometimes disparate works; some may consider this frustrating, while others will appreciate the intellectual challenge that it offers. I will focus on two sub-themes that are particularly powerful, both curatorially and conceptually: the physicality of the body and the male gaze. While these themes in no way represent the whole of the exhibition, they provide important perspectives on issues of gender and sexuality and challenge how we conceive of these ideas.

Immediately upon entering Breaking the Mold, viewers enters a darkened space containing depictions of our bodies in their rawest form. The mood of the room is remarkably different than in the rest of the museum - it is liminal space that seems more akin to church rather than a museum. First, we see Kiki Smith’s untitled 1992 sculpture of a hide-like human skin made out of latex with a protruding glass spine. Set upon a white table with a downward-pointing light illuminating the sculpture, it is as if Smith’s work is a holy relic or a body waiting to be operated on. The experience of viewing this work is extremely visceral, as it lays out the crux of human existence—our bodies—in a sober, yet poignant manner. By using glass to create the spine, easily one of our most fragile yet important parts, Smith reminds us of our delicate corporeality. What is particularly interesting in the context of this exhibition is that the viewer cannot ascribe sex to the depicted body. This allows everyone to access the work and envision their own bodies through Smith’s sculpture - an impact that is diminished by the museum’s extraneous clarification that the model was a woman. In her analysis of the similarly undefinable patient in Thomas Eakins's The Gross Clinic (1875), Jennifer Doyle states, “The absence of a gender for the patient's body reminds us that we fully expect the body to have one.” Smith’s sculpture is a powerful opening note and reminds us that, even in an exhibition centered around gender, its absence can say just as much.

Kindred in its anatomical exploration, What Will Be Remembered in the Face of All That is Forgotten (2014-2015) by Tavares Strachan depicts a neon skeletal and cardiovascular system that illuminates the other half of the darkened room. Neon tubes that comprise the sculpture pulse, suggesting a heartbeat or waves of energy rippling through the body. The piece has a surprising presence to it—a feeling that is exacerbated through its pose. With outstretched arms, the skeletal figure seems to acknowledge the viewer’s presence and invites them to gaze upon a figure that is simultaneously present and absent. While gender is indeterminate in Smith’s work, it is at the forefront of the conversation within What Will Be Remembered. The didactic text describes the work as “a portrait of someone who was made invisible” - Rosalind Franklin. During her career as a chemist, Franklin faced sexism constantly. Her discoveries led to James Watson and Francis Crick finalizing the structure of DNA, yet she is egregiously left out of this history in many contemporary accounts. Franklin is yet another woman whose important contributions are eclipsed by those of men; regarding this erasure, Strachan finds importance in “creating a platform for us to think about what we consider to be important and why and how, and who gets to decide those things.” The artist’s use of a skeletal figure not only recalls the x-rays used in Franklin’s research, but issues of mortality and legacy. What Will Be Remembered reinserts Franklin’s contributions into contemporary consciousness, but it is important not to historicize the difficulties she faced. Gender and power are just as interwoven today as they were in 1953.

In an exhibition that explores gender dynamics in visual art, John C. Kacere’s Light Purple Panties, Zippered Slip (1971) is a controversial inclusion. The painting depicts the lower back of a woman who has partially unzipped a silk, off-white dress, revealing her underwear. Kacere’s photorealistic style exposes each curve of the model’s body, particularly her buttocks which are framed by the unzipped dress. Notably, any identifiers of the sitter’s personhood are stripped from her - Light Purple Painties is not a painting of a woman so much as it is a painting of women. Through framing and subject matter, the male gaze is inescapable. Kacere’s paintings has attracted ire from many viewers, but particularly feminists who readily see their exploitative nature. In a 1976 letter to the Speed, he links the women’s movement to the difficulty many women have with his work, but attests that “I’ve found that more women like my paintings than those who don’t.” The didactic text delves into the problems inherent with the piece as well as the artist’s perspective on its creation; ultimately, the viewer is left to draw their own conclusions, which feels apt for work with such a contentious history. Light Purple Panties is part of a larger conversation regarding power, art, and display that has been going on in feminist circles for decades, but has been more recently thrust into the public eye in the wake of discourse around Confederate monuments. Like monuments, museums inherently place value on artworks and the ideas they represent by making them visible. For this reason, it is imperative that the Speed Art Museum further cultivates a conversation, through lectures tours, programming, or other forms of public dialogue, regarding their institutional values, what it means to display work like Light Purple Panties, and what the audience can learn from it.

Positioned on the same wall as Kacere’s sexualized figure, the Big Red Rose–RFGA (2004) by Ghada Amer subverts the male gaze by recontextualizing pornographic images of women. Frenzied, partial female figures cover the surface of the canvas in a manner reminiscent of Jackson Pollock’s paint drips. Each of these nude figures “are sourced directly from pornography, yet Amer presents them in a way that denies easy gratification.” Further complicating the surface of the piece, the artist’s frequent collaborator, Reza Farkhondeh, painted three red roses that dominate the composition. The roses, symbols of love and romance as well as femininity, seem to initially contrast with the ribald sexuality exuded by the pornographic actresses. Amer complicates our understanding of feminine archetypes, however, stating, “For me images of women taken from porn magazines and images of women in fairy tales are the same. … I try to empower myself by trying to realize that both are just imposed on me and I just have to navigate between one or the other according to the situation.” The push and pull between Light Purple Panties, Zippered Slip and the Big Red Rose–RFGA is quite compelling; while the former is yet another instance of the male gaze in visual art, the latter presents a break in that dynamic - an artist reclaiming the female body from the very history that Kacere’s painting belongs to. Intelligent curatorial decisions allow works of art expand beyond their own borders, and the conversation between Kacere and Amer is just one thread that exists in this exhibition.

While Breaking the Mold is undoubtedly multifaceted in its exploration of gender, sexuality, and race through modern and contemporary art, it ultimately suffers from its breadth. The topics at hand are infinitely complex in and of themselves, with each intersection of gender, sexuality, and race deserving its own exhibition. As a viewer, I sometimes found myself performing mental gymnastics to draw connections between disparate works. Perhaps this could also be a strength, as Breaking the Mold intrinsically promotes dialogue. This takes a multitude of forms: between the curator and the artworks, between the artworks themselves, between the museum and the public, and on an interpersonal level as the viewer walks through the gallery with friends or family. On the Speed Art Museum’s website, the description of this exhibition opens with the question, “How can contemporary art facilitate discussions about gender and power?” If this is the goal curator Miranda Lash set out to accomplish, it certainly gives us much to think about. Still, I left feeling slightly dissatisfied - the exhibition contains great pieces, but what does truly mean for them to share a space? Would it be more coherent if it contained just a few thoroughly-investigated topics? What if it featured more pieces outside of the permanent collection? Despite its shortcomings, Breaking the Mold is refreshing for its nuanced investigation of identity through visual art. Hopefully, the momentum produced by this exhibition is something that Louisville-based museums and galleries can continue to build upon.

-

Breaking the Mold: Investigating Gender at the Speed Art Museum is on display until September 9.

The Speed Art Museum is located at 2035 South 3rd St, Louisville, KY 40208 and is open Wednesday-Saturday from 10am-5pm and Sunday from 12-5pm.

Notes:

-

Doyle, Jennifer. Sex Objects: Art and the Dialectics of Desire. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

- Ghada Amer

- Speed Art Museum

Kevin Warth, Contributor to Ruckus

7.24.18

Tavares Strachan, What Will Be Remembered in the Face of All That is Forgotten, 2014-2015. Neon, pyrex, stainless steel, transformers, steel wires, cable. Gift of Speed Contemporary. Image courtesy of Tavares Strachan. Photography by Tom Powel Imaging.

Kiki Smith, Untitled, 1992. Latex, glass. Gift of the New Art Collectors and museum purchase. Image courtesy of the Speed Art Museum.

John C. Kacere, Light Purple Panties, Zippered Slip, 1971. Oil on canvas. Gift of the New Art Collectors. Image courtesy of the Speed Art Museum.

Ghada Amer, The Big Red Rose—RFGA, 2004. Acrylic, embroidery, and gel medium on canvas. Gift of the New Art Collectors and museum purchase. Image courtesy of the Speed Art Museum.