PHOTOS: Ruckus

︎ 849 Gallery, Louisville

Cinema of Distraction

Soon after entering Cinema of Distraction at 849 Gallery, it becomes evident why artist Christopher Ottinger says he has “a touch of mad scientist” in him. His installations are comprised of items that feel out of place in a gallery: cathode ray tubes, a fog machine, whirring motors, and tangles of wires. In this solo exhibition, the artist has transformed 849 Gallery into a science lab of sorts, requiring viewers to approach his experimentations with careful observation. There is an evident homage to gadgets and technologies of the past, yet Ottinger’s artwork feels strangely futuristic. By engaging with antiquated forms of cinema and the emerging discipline of media archeology, the artist complicates our understanding of history, technology, and temporality.

Ottinger cites media archeology as an influence in his examinations of history and technology. Erkki Huhtamo, a leading figure in the field, says a primary goal of media archeology is “to study the cyclically recurring elements and motives underlying and guiding the development of media culture.” If we look at the recent resurgence of outmoded media–Polaroid film, 8-bit gaming, vinyl, et cetera–it becomes evident that technological evolution is not linear. Rather, our culture tends to remake and reexplore old ideas in new ways - particularly techniques of communication that have been lost, neglected, or obscured. Ottinger even argues that the Lascaux cave paintings, regarding their depiction of movement, are the first instance of cinematic form. Media archeology is an important field to consider in context of Cinema of Distraction, as it provides a framework in which multiple histories and temporalities can coexist.

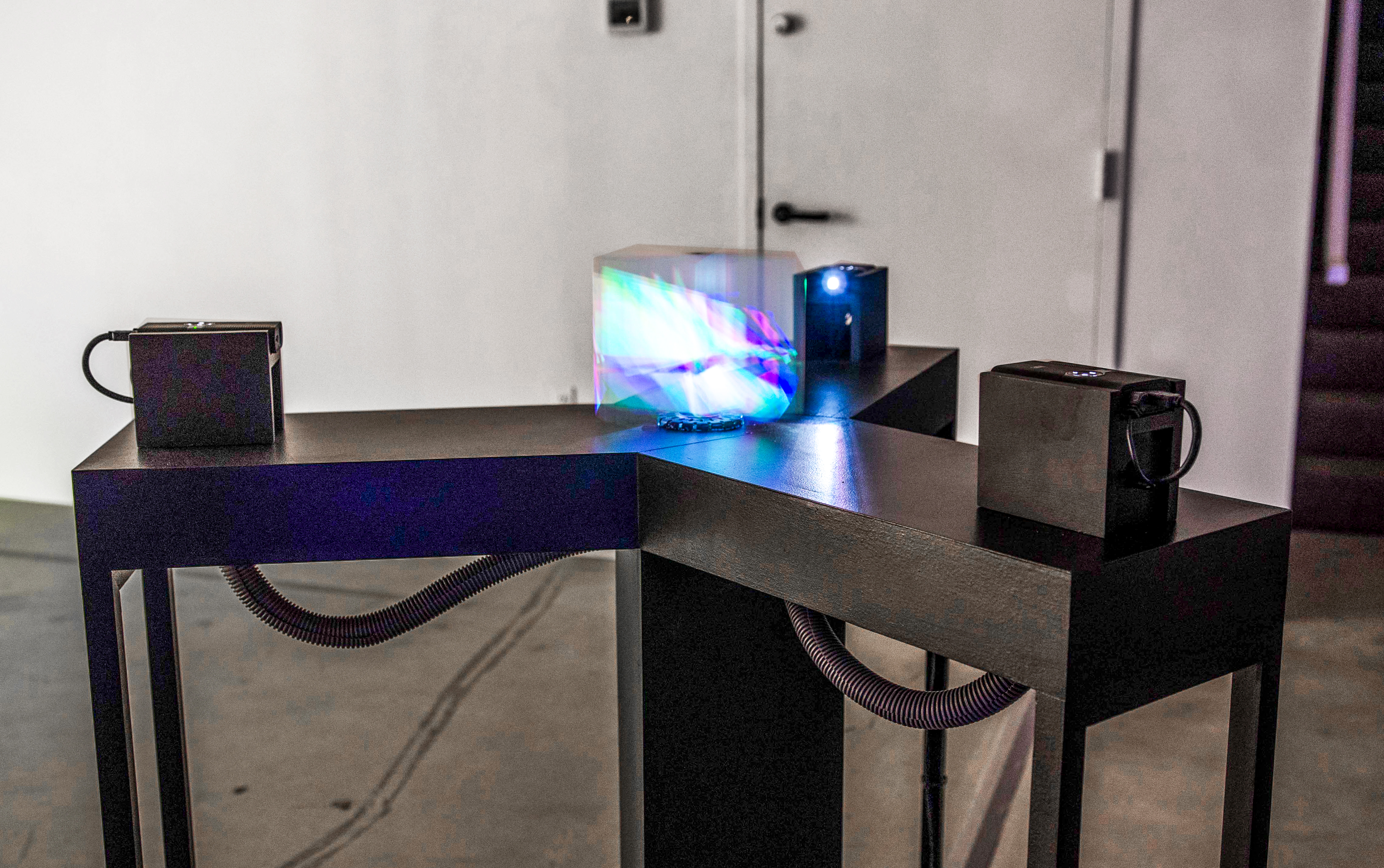

In Ottinger’s installation NTSC Ghost v.2.0 (2018), three stages of technological evolution converge: zoetrope, analog television, and digital projection. The zoetrope was a 19th-century invention and early form of animation; by spinning a series of pictures on the wall of a cylinder, the device creates the illusion of a moving image. Ottinger complicates this relatively simple mechanism by integrating modern technology. Three small projectors point towards a rapidly rotating screen positioned in the center of a pedestal, each projecting an image of television color bars. The speed of the spinning screen alters the viewer’s perception of the colors. They shift and oscillate, seeming to create a moving hologram. While NTSC Ghost v.2.0 builds upon an antiquated form of animation–the zoetrope–it creates a visual phenomenon that feels more at home in science fiction.

Also building upon multiple epochs of media, Blue Ghost (2018) creates an illusion of presence. When a viewer initially approaches the piece, it appears to simply consist of two small monitors transmitting static and a piece of glass between them. Upon close observation, however, it becomes evident that only one of the monitors is on - the angle of the glass transposes an image of static onto the blank monitor. This type of illusion is known as “Pepper’s Ghost.” The technique rose to prominence after a demonstration by John Henry Pepper in 1862, but was originally conceived of in the 16th century by Giambattista della Porta. This carnival trick of the past is still used today, from holograms of Tupac Shakur and Michael Jackson to the ghosts that appear in Disney’s Haunted Mansion ride. By fully unveiling its artifice and integrating 20th-century electronics, Ottinger deconstructs the Pepper’s Ghost phenomenon.

A series of blue lights, positioned underneath the pedestal that Blue Ghost sits on, flood the room with a strange, haunting energy. The tonality of the light matches that of the infamous “blue screen of death” - a notification that a Windows operating system has experienced a fatal system error. Utilizing signifierers of death in both the blue light and powered-off monitor, Ottinger asks if these “dead” media are truly gone or merely slumbering. As the individual titles suggest, perhaps the most precise word to define these outmoded forms of media is ghost; they are often forgotten or obscured, existing in a perpetual liminal state. Still, media “ghosts” hold important information about our collective past that can be uncovered in disciplines such as media archeology or in artistic practices such as Ottinger’s.

Philosopher Jacques Derrida’s concept of hauntology provides another useful framework for interpreting Cinema of Distraction. In Specters of Marx, Derrida outlines an ontological paradox: the ghost properly belongs to neither the past nor the present, thus leaving no temporal point of pure origin. Media ghosts are similarly atemporal, to follow this logic, and resurface every few hundred years in a new context. We seem almost incapable of a full technological reinvention and are instead stuck in a recurring loop; designs of the past rarely disappear - they are built upon, revisited, and reinvented. Furthermore, the deconstructive notion of “always already” can be applied to Ottinger’s exhibition. As media archeology illustrates, what may be considered “new” forms of communication have indeed always existed, merely waiting to be revealed or noticed. Ottinger’s work unveils the “always already” in our collective media culture.

Ottinger complicates the narrative of technological evolution as a linear path; instead of new models replacing old ones, we constantly look back to the past whether we are fully aware of it or not. This idea became even more apparent to me as I researched the techniques that the artist builds upon. Technologies that I ascribed to certain periods often had precedents a century or two prior to my imagined date. Cinema of Distraction, as does media archeology, provides an introspective look at modes of communication. Even the exhibition title itself draws reference to early media history - the short, non-narrative “cinema of attraction” films of the late 19th-century, when the simple spectacle of the moving image was enough to captivate viewers. Is the basic wonder of moving imagery still able to captivate the viewer’s attention? Almost 130 years later, we now find that cinemas of distraction are always at hand - from Snapchat to YouTube clips to phone games. Some may argue that this sense of marvel is lost on our generation, but I see it manifest in our desire to capture movement through GIFs and Vines. With each of these, a clip is repeated endlessly for no purpose other than temporary fascination. Nevertheless, Ottinger’s work manages to evoke a sense of wonder despite its simplicity. To view his installations is to witness the past, present, and future coalesce.

-

Cinema of Distraction is on display 849 Gallery until 04.13.18

849 Gallery is an associated space of Kentucky College of Art + Design, located at 849 S 3rd St, and is open Thursday & Friday 11:30am-2:30pm, or by appointment, 502.873.4373.

Notes:

- Derrida, Jacques. "Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, The Work of Mourning & the New International." Translated by Peggy Kamuf. London: Routledge, 1994.

- Huhtamo, Erkki. "From Kaleidoscomaniac to Cybernerd: Notes toward an Archaeology of the Media." Leonardo 30, no. 3 (1997): 221-224.

- Christopher Ottinger

Kevin Warth

Contributor to Ruckus

4.7.18

Time enough at last... (2018). Wood, enamel, cathode ray tube, video.

NTSC Ghost v.2.0. (2018). Wood, enamel, electronic components, video.

Blue Ghost (2018). Wood, enamel, acrylic panel, cathode ray tubes, CFL, electronic components.

The Entire History of You (TV Ghost) (2018). Wood, enamel, extension cord.