Above: Noel W. Anderson, Do you see the light?! (2022). Photos courtesy of KMAC Museum

Erasure’s Edge

Review

Noah Randolph

Walking into the second-floor galleries of KMAC Museum, the blue paint of the gallery wall at the front of the space reflects onto the hardwood floor. On the wall is Noel Anderson’s List of Leaking Terms, a mixed media work made of athletic towels and cut-out letters, meticulously incised from the rubber skin of basketballs. The blue of the wall matches the blue lines on the white towels, with the letters sitting atop the lines as if notes on a page. They state:

leak poze

discharge expose

trickle blab

drip collapse

seep pourous

breach write

break fess

Each of these are synonyms of the first word, leak. This is the introductory work in the exhibition Erasure’s Edge, which showcases new meditations on one of Anderson’s primary artistic techniques—erasure. Both literally and figuratively, his work meditates on the meanings, histories, and potentialities within the act of erasing. While this particular list of words may seem antithetical to this, Anderson took this list from the pages of his own notebook, saying that leaks are representative of the relationship between each work in his oeuvre, from the pages of Ebony to the images of police brutality to the referents within the works themselves.

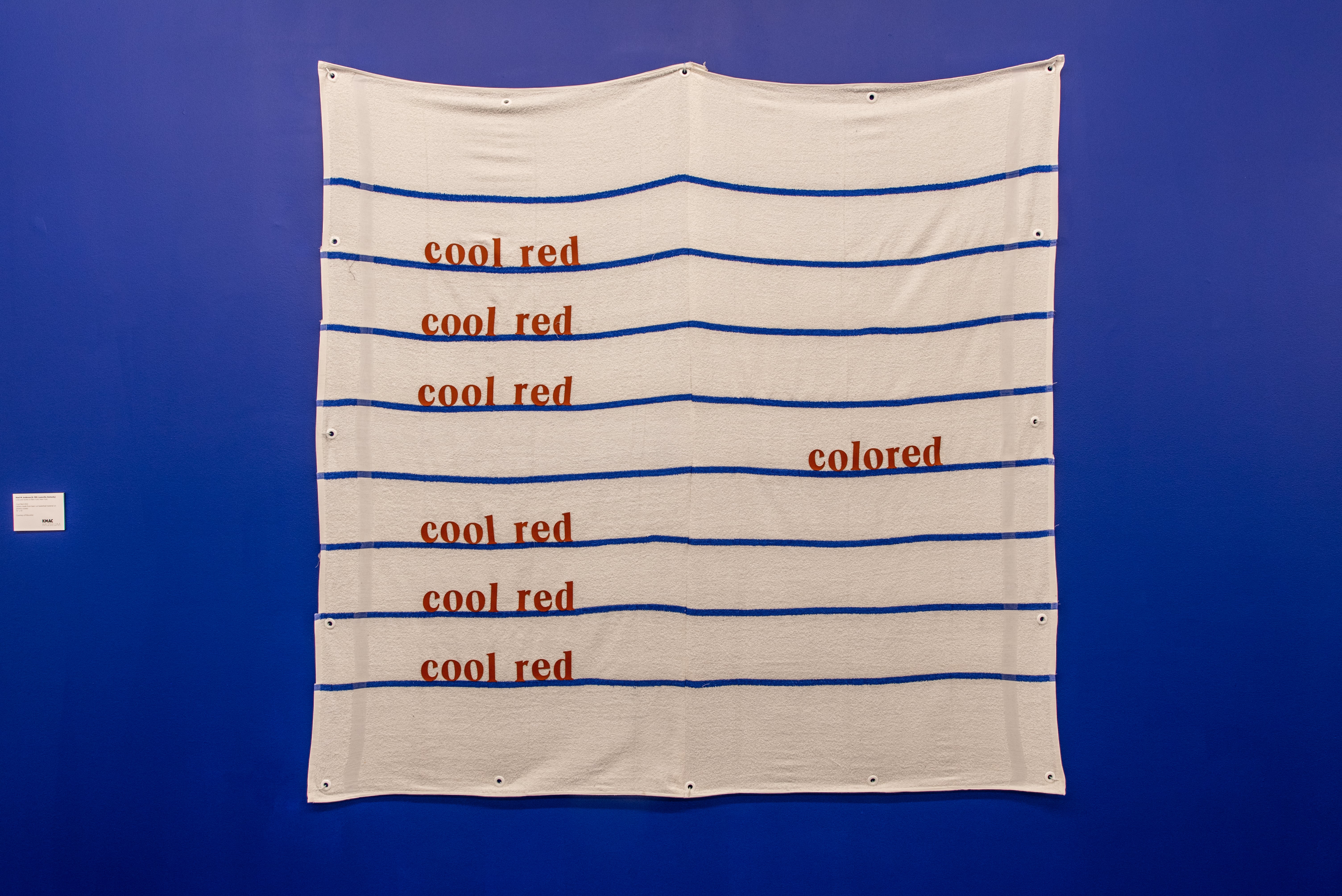

In a related work titled Cool Red, Anderson presents another list made from cut-out letters on athletic towels:

cool red

cool red

cool red

colored

cool red

cool red

cool red

As if from a Jim Crow-era water fountain, suddenly the leak bursts. The anagram observed by Anderson points to Christina Sharpe’s concept of “anagrammatical Blackness,” or, “Blackness anew, blackness as a/temporal, in and out of place and time putting pressure on meaning and that against which meaning is made. . . As the meanings of words fall apart, we encounter again and again the difficulty of sticking the signification.” With the basketball skinned words balancing tediously on the thin blue line of the towel, the blue becomes more of a jarring presence of police power—one that targets and focuses on Black communities, whose words and descriptors have often leaked into sports broadcasting. Yet, of course, a separation can be made as long as Blackness is representing the right team. This separation amounts to erasure.

More pointedly, for the work Under Erasure, a mugshot from his constantly growing archive of images, woven and stretched, is then selectively bleached, removing the dye—and therefore skin tone—from the figure’s face. The work is one of nine mediations of the same image, variably bleached, inversed, dyed, and obscured. In this, Anderson serializes the erasure of the mug shot in order to “consume their power. . . and thus drain their negative magic.”1 This act of erasure is more than a Rauschenbergian claim of dominance over abstraction. Rather, it questions the validity of the image itself, acknowledging the mugshot and over-representation of Black criminality as an abstraction of reality and demanding the subjects right to opacity. As stated by Tina Campt in her own study of mug shot archives, confronting such imagery allows Anderson “to consider the desire for photographic capture as itself a pernicious instrument of knowledge production used to subjugate Black bodies both in the present and into the future.”2

But what does the infliction of erasure mean? In the hyper-visibility of Black pain in the 21st century, Anderson sees "the erased page (as) a promising site/sight," channeling Katherine McKittrick's concept of futurity.3 Within academic and artistic discourses, McKittrick posits that analyses or (re)presentations of Blackness, even when attempting to reveal injustice or inequality, rely on the existence and continuation of Black trauma. Through the bleached image, the plucked tapestry, and the folded fabric, Anderson's work denies this paradox, uncovering an artistic praxis in which "racial pasts can uncover a collective history of encounter—a difficult interrelatedness—that promises an ethical analytics of race based not on suffering, but on human life."4 This is furthered through Anderson's use of Ebony magazine—the collecting of which he says led to his initial understanding of his own archival practice. Ebony began in 1945 with the purpose of celebrating Black life and circulating this nationally in a country in the throes of Jim Crow. In utilizing this, Anderson successfully mines an archive that allows for an exploration of Blackness that does not depend on the depiction of pain. This, though, is not to say that Anderson avoids or negates this aspect—it still leaks.

Also founded in Chicago in 1928 were the Harlem Globetrotters, a basketball team made solely of Black players. As they began to play outside of Illinois, the team began to hail from Harlem to associate themselves with the geographic center of American Blackness. Along with this, the team became a pop culture phenomenon, replete with celebrity and merchandise. One such piece of merchandise, a coloring book, is the source for an untitled diptych. As shown within the word list works, the dialectical relationship between race and athletics is a critical point of departure for Anderson. Unlike the bleached mugshot, the coloring book page was already void of color—a convenient factor given the Civil Rights era vintage of the cartoon drawings. The absence of the Globetrotter’s Blackness is furthered in the content of the work. On the left panel, the player tosses a ball behind his head, telling the viewer “NOW YOU SEE IT,” only to vanish in a puff of smoke on the right panel, stating “NOW YOU YOU DON’T!” The second panel was Anderson’s own erasure, pulling the Globetrotter out of the page to not only invoke the trope of the “trickster” that is invariably associated with the Harlem Globetrotters, but also to reveal the necessary reality of “the recognition and acceptance of a consistent position of invisibility for Black subjects (and) seeing this as a power to be flexed when necessary.”5 Through his use of tapestry, Anderson is able to play with this desire of the viewer—the simultaneous granting and denial of the whole image. This is especially true of Untitled in which an image of Julius Erving, the legendary small forward, is woven into Jacquard tapestry. However, the tapestry is picked, with Anderson pulling strands of the fabric. As the viewer approaches, the image of Dr. J falls into an abstracted jumble of soft technicolor fibers. Pointing to the pointillism of Georges Seurat, Anderson stresses this optical capability of the material. The painstaking process in which Anderson literally picks the cotton of the image simultaneously reveals and abstracts while enticing the viewer to touch the surface—a craving that devolves and problematizes given the weighted imagery of his tapestries.

Anderson’s work is largely a critique of modernism and modernity, in which he often employs the forms of canonical artists as a way to question the legacies written by art history and their broader socio-cultural effects. In the work Their Desire “It is what it is”: Black Spirit’s Concealment, the figure sitting for a mugshot is obscured by the signature radiating rectangles of Frank Stella’s Black Paintings. The poster boy for minimalist painting, Stella famously commented on the meaning of his work by stating, “What you see is what you see.” In the midst of the Civil Rights movement, minimalism fulfilled a demand for “an honest, direct, and unadulterated experience in art. . . minus symbolism, minus messages, and minus personal exhibitionism.”6 The objective neutrality of minimalism served to make the works and the artists themselves a part of the larger sphere of brutality as expressed through corporate greed, stifling of protest, and the growing military-industrial complex that continues through today. This quotation is less appropriation than it is interpolation, one that itself moves towards interpellation, to invoke Fred Moten.7 By framing a Black man’s mugshot with Stella, Anderson denies this erasure and the simplicity of “seeing what you see,” simultaneously questioning Stella’s objectivity and widespread representations of Blackness.

Originally from Louisville, Anderson also looks to the late Sam Gilliam for another method of erasure: the fold. Gilliam’s suspended canvases were a revolution within the quest for modern painters to exploit the picture plane, describing his own work as “an act of pure passage.”8 Within that passage is obscurity, one that once again refuses the viewer’s desire to have access to the entire image. Anderson uses this unstretched suspension in Untitled (After Sam Gilliam). Through draping, Anderson is able to take these representations and question them through folding the images onto themselves, urging the viewer to look closer at what is (or isn’t) there. The source image within the work alludes to a different passage altogether as well as to the historical relationship between African art and museums, showing an unnamed African sculpture. Through the twentieth century, looted African art was primarily under the auspices of ethnographic museums, wherein they were studied and examined by the canonical disruptors of European art, only to be appropriated and pillaged for the formal qualities that would serve as the unrecognized foundations of modern art.

Anderson knows these erasures well. In his work, he has found a way to address them and those left in its colonial wake while practicing a socioacupuncture of the images that have been created to hold the erasures up. His archival practice heeds McKittrick’s call for an ethical analytics of race while avoiding the temptation described by Saidiya Hartman “to fill in the gaps and to provide closure where there is none.”9 Do you see what you see? Was it ever there at all? This is the edge of erasure that Anderson creates—straight, no chaser.

-

Citations:

- Kellie Jones,Eyeminded: Living and Writing Contemporary Art (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 17.

- Tina Campt, Listening to Images (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017), 94-96.

- Noel Anderson, Erasure’s Edge, KMAC, Exhibition Text.

- Katherine McKittrick. “On Plantations, Prisons, and a Black Sense of Place.” Social & cultural geography 8, Vol. 12 (2011): 948.

- Noel Anderson, Erasure’s Edge, KMAC, Exhibition Text.

- Anna C. Chave, “Minimalism and the Rhetoric of Power,” in Art in Modern Culture: An Anthology of Critical Texts, eds. Francis Frascina, Jonathan Harris, 264-281. (New York: Phaidon, 1992), 266.

- See Fred Moten, Black and Blur (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017).

- Sam Gilliam and Annie Gawlakm “Solids and Veils” in Art Journal 50, no. 1 (1991): 10.

- Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” in Small Axe 26 (2008): 8.

Installation view of Erasure’s Edge at KMAC Museum

![A royal blue wall with a rectangular artwork made of white athletic towels with blue lines, stitched together so the blue lines meet and resemble ruled paper. Letters made from the material of basketballs spell out the words “cool red” six times in a vertical column, aligned with the left side of the composition. In the middle on the right side, the same letters spell out the word “colored.”]()

Noel W. Anderson, Cool Red (2022)

![A white wall with nine 16” x 20” stretched jacquard tapestries hung in seemingly random placements. Each tapestry features the same found mug shot image of a Black man, but each tapestry is altered in a different way: many of them are bleached, one has the threads over the man’s face pulled loose into a field of small, rainbow-colored loops, one has the values inverted to resemble a film negative, and two are hung upside down.]()

Installation view of Erasure’s Edge at KMAC Museum

![A white wall with a jacquard tapestry draped and hung from black cords attached to silver hooks at various angles. The tapestry is mostly light blue with the image of a carved African statue visible among the folds and curves of the material.]()

Noel W. Anderson, Untitled (after Sam Gilliam) (2022)

![On a white wall, a stretched jacquard tapestry with the image of a mug shot is patterned with concentric rectangles emanating from the center, alternating between light and dark hues.]()

Noel W. Anderson, Their Desire “It is what it is”: Black Spirit’s Concealment (2022)

![A gallery space with white and royal blue walls. On the wall to the left is a small stretched jacquard tapestry and a floating frame that comes out from the wall at a ninety degree angle, featuring a mixed media collage with shades of red and blue. On the back wall is a large stretched tapestry with an image of a basketball player and white and blue athletic towels with text on them. On the right wall is a large mixed media artwork draped from a hook and an assortment of smaller athletic towels with text on them.]()

Noel W. Anderson, Cool Red (2022)

Installation view of Erasure’s Edge at KMAC Museum

Noel W. Anderson, Untitled (after Sam Gilliam) (2022)

Noel W. Anderson, Their Desire “It is what it is”: Black Spirit’s Concealment (2022)

Installation view of Erasure’s Edge at KMAC Museum

-

1.21.23

Noah Randolph (he/him/his) is a PhD student in Art History at the Tyler School of Art and Architecture. His research focuses on the intersections of the public sphere and memory.

1.21.23

Noah Randolph (he/him/his) is a PhD student in Art History at the Tyler School of Art and Architecture. His research focuses on the intersections of the public sphere and memory.