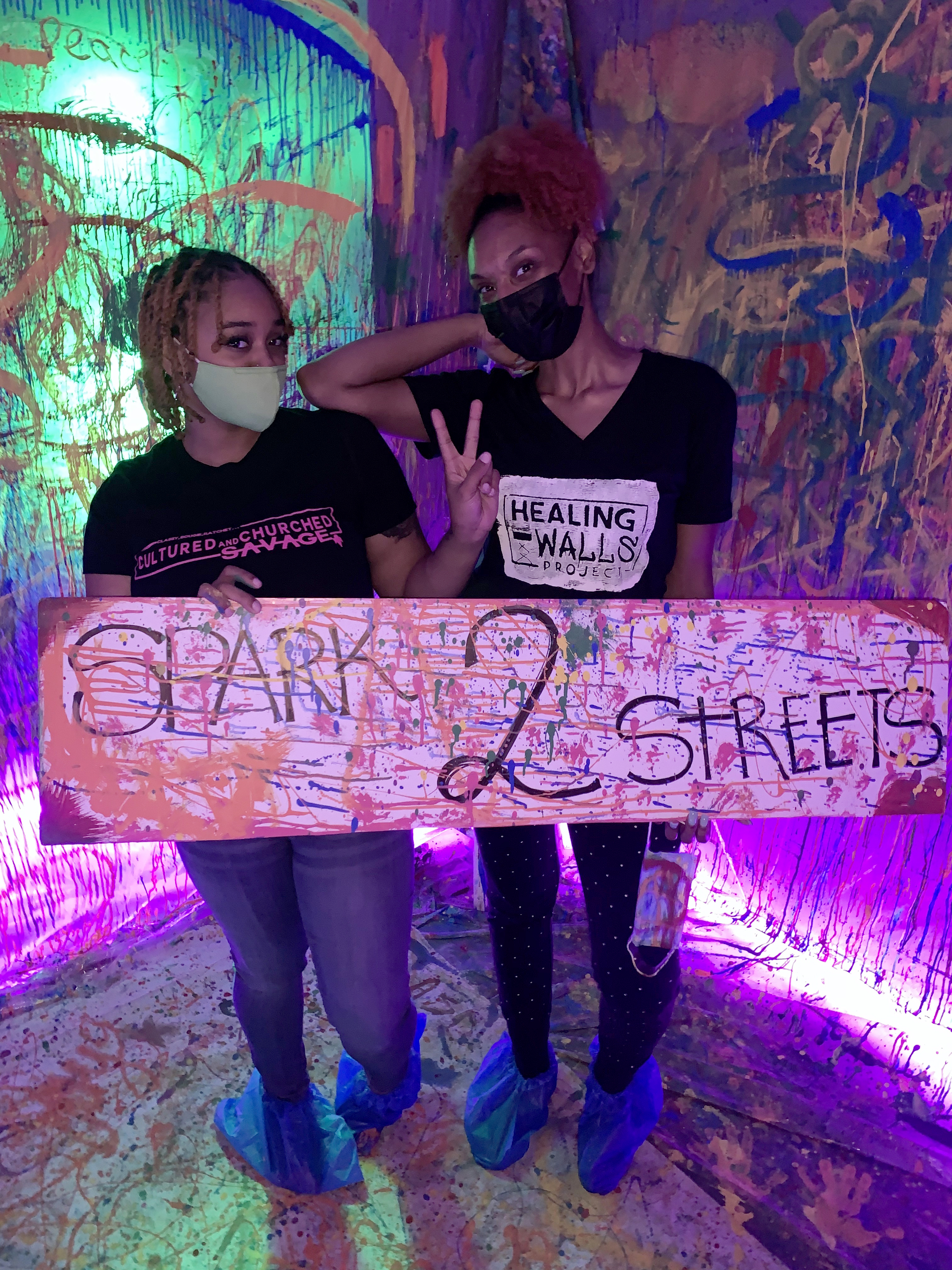

Above: Artists working on a mural organized by Healing Walls Project

Healing Walls Project

Q&A

with Anna Blake

Last year, artist, activist, and curator Ashley Cathey founded the Healing Walls Project to empower BIPOC artists in their creative processes while facilitating education and healing. In anticipation of their upcoming Louisville mural cycle, I spoke with Cathey, founder and CEO, CFO Michelle Johnson, and Tabin Ibershoff about the need for trauma-informed arts opportunities, community healing, and social justice within the arts.

Anna Blake: The mission of the Healing Walls Project is to “cultivate a network of artists that can build with one another and amplify each others’ stories through the creation of public art.” Can you speak about what inspired you to take this initiative?

Ashley Cathey: I was inspired by pain. By my own particular struggle with being heard and speaking and expressing myself through art. That same exact feeling was being reflected in people around me and people that look like me. We weren’t allowed to publicly speak through our art. Through working heavily in public art, I found out how impactful it truly was. From the time that you start to put up work in the community to the time that you reveal it, it becomes a part of the people there. It automatically creates this relationship with you and the community and you’re building something together because they’re constantly seeing you do it. However, I noticed that I was usually the only Black person, the only woman, or the only Black woman. It’s important in history that everyone’s voice is heard and right now only a certain amount of people are being heard and those are usually cisgender white men and that is injust. That is not the only story.

In public art, it’s less about my own narrative and more about speaking on behalf of the community and with the community; the actual geographic area in which the work is being placed as well as the community I represent—which is Black people—at all times, wherever I am.

The Healing Walls Project was directly inspired by an interaction I had with a person that’s now my mentee. She was having a hard time, I was having a hard time, and we were able to heal by creating art together. Most of it is someone being there for questions, someone being there to support you, and someone there to let you know that you can do it even if you don’t see someone else like you doing it.

I want to fill in that knowledge gap because most of the time, feedback was “yes, we know you can do this art, but you’re not good enough to get this building.” But who says what's “good enough?” Who says what art gets to be seen? That typically has to do with access. If the skill level is not there, then how can one get better? Just saying you’re not good enough and you can’t do it doesn’t offer a resolution to that. So there’s this repetition of choosing the same people who have access to the knowledge, not because they are more talented or that their narrative is more important.

AB: You emphasize the therapeutic capabilities of visual art and creation. That’s something that has been on a lot of people’s minds in the last year. You’ve spoken about this a little bit, but can you elaborate on how these murals provide healing for artists and the communities that come in contact with them?

AC: Art itself is generally very therapeutic to me because it was my safe space. The visual part of your artistic practice is something that you do in solitude. There’s no approval process and you just do it; it satisfies you in that moment. Then, when you are able to express yourself out loud in a public forum, there is a value associated with that representation. Oftentimes, not seeing people that look like you is a reason why you don’t try things. Connecting with my community is healing and is something that speaks to our narrative. The history of Black people in America has been of a lot of pain and art can shed light on a story and bring joy. By doing public art, we’re able to have agency over our own story. Maybe someone is not expecting to see this art; maybe they can’t hear people when they’re protesting but art speaks volumes when words fail.

Then there’s the actual physical labor of doing art. It takes a bit of mindfulness. Sometimes you get into a motion, and it allows you to free yourself. It’s just like someone taking a jog, doing meditation, or even singing. It’s an instant gratification because you are moving your body. The physical action of creating murals is tedious and you do it alone.

AB: You mention that, physically, murals are done alone. But there is also a factor of community involvement. What role does the community have in relation to the mural?

AC: With the Healing Walls Project, the difference is that we don’t just go into a community and throw up a mural. We allow the community to be a part of the choosing of the art. We ask them what they want to see, what they want to talk about, what makes them feel happy and doesn’t trigger them; sometimes I do see public art that is triggering. In the last year [in Louisville], people have come all over and speaking on Black safety, on Black lives mattering, but they had no connection to that narrative. That is an issue.

There are people within a community wherever you are that are also artists, so we do a call wherever we go. We’re in St. Louis right now and most of the artists we’re working with are from St. Louis, from the community, and from the neighborhood in which we’re putting the art. We open our program to recreational artists and to commercial artists. There are different levels of participation; you might be a professional muralist but you’ve never done a mural in your own neighborhood. Or you may have only worked in your neighborhood and never outside of it.

Another way the community gets involved is through intentional engagement. That could be recreating the mural on a coloring page, the community actually participating in the mural, or our two events. One is called Pull Up And Paint where we put up micro-, temporary murals at different businesses that support and advocate for public art and healing and people can participate in these murals while patronizing these businesses. This way, you know that art is coming to your neighborhood and it’s an opportunity for people to do something that is mindful.

The other event is Spark to Streets. We do seven immersive rooms and create a journey from the spark of creation all the way to taking your art into the community, either in the streets or in galleries and coffee shops. There is a part where you start to create and that’s separate from the part where you feel valuable enough to take your art into the community. So these seven immersive rooms will guide you into confidence through healing. At the end, you do a reflection on this moment that you took for yourself where you took 75 minutes to create art, be mindful, and interact with your community. Because of COVID-19 we’ve had to shift a little bit, but these are the ways that the community gets involved. A lot of public art is about community because they are the people that have to see it every day.

AB: The rotating murals that the Healing Walls Project produces create an evolving art piece. This is something I’ve never seen in a public art initiative; can you describe the significance of this?

AC: The rotating murals came from feeling as though I had to put my best foot forward in every single opportunity. That’s something that BIPOC artists go through all the time. So what I wanted was an opportunity to allow artists to get to have the experience but know that everything is temporary. We want to allow people to grow and not be judged while they are growing and in the process of learning. People of color and Black people in particular are going through a serious amount of trauma on a daily basis. When you have to create art, it can also be a source of trauma because you don’t have the same access, the same amount of knowledge, but you still want to express yourself knowing that you could do better if you had the knowledge.

When I did my first or second mural, I never even signed it because I felt so ashamed. Because I knew that this work was not a representation of what I was capable of doing. As a Black person, I have to represent my community, and maybe if when I put up this art that doesn’t meet my expectations, they wouldn’t give someone else like me a job because I did so badly. A lot of people worry about that because of the lack of opportunities. So the rotating murals creates so many opportunities for growth and creating.

So for the first mural, we want to nurture and guide. Even if you’ve been painting your whole life, we still want you to get the very basic knowledge with a lead artist. Then by your last mural, it will stay at the location as something you can be proud of.

AB: It feels very profound that, when most contemporary art revolves around ownership and preservation, the Healing Walls Project is going a different way.

AC: We are radical. What we are doing is revolutionary. Taking up space for BIPOC artists is revolutionary. Adding art into that and teaching one to heal themselves through something expressive is revolutionary and very radical.

Deciding that I will give you this beautiful work, but I’m going to take it away because I have to grow, is radical in the art world where how long something’s been around is important. With public art, the ownership is with the community. When it comes to artists that need healing, it’s hard to do that because you need to take the time to nurture your process and really learn.

Tabin Ibershoff: I would love to mention that, like Ashley said, the gatekeeping, the “not good enoughs,” and what is inherently supremacist is this idea that there’s only one way to be. When Ashley says that we are radical, we are coming at everything with a sense of peace. As a white person, I’m so glad to work for and with these visionaries and be able to uplift them behind the scenes. I’m glad to have space where I can use some of my skills as a networker to create space because that’s healing for all of us.

AB: What can people in the greater Louisville area expect from the Healing Walls Project in 2021?

AC: We are going to do a cycle here coming at the end of the summer and are doing some professional development murals. We are doing a community-based mural for Kroger at 28th and Broadway working with residents of West Louisville. Right now we’re doing a professional development mural at Russel Tech Business Incubator. There will also be a very large scale mural that we will release information on very soon. By 2022, we will have done at least fifteen murals in Louisville. We’ll do workshops on healing where we learn how to cope and use art as a coping mechanism.

There’s also going to be business development workshops; our artists will be able to participate in Tawana Bain’s Boss Up to get them equipped to run their own small business and work as an artist. We can also help artists get hired. Businesses can reach out to the Healing Walls Project to be more intentional about the art that they’re placing in their spaces. We work heavily with the community and we have a “Rolodex” of BIPOC artists who need healing and are amazing to work with.

I hope to be able to do a festival here where we can go into one community in the West End and beautify it, because there is a lot of healing needed there. I’m wanting to bring more into my city that sometimes feels hopeless. The Healing Walls Project will allow BIPOC artists to take up space when so much of the arts community does not allow us to.

AB: In addition to Louisville and St. Louis, are there any other cities that you serve or hope to serve in the future?

TI: We are looking next at Tampa. I had the ability to go down there and meet some artists and see some visual art down there, some public art. That’s definitely coming up, I think early 2022.

AC: Also Savannah, Georgia. This fall we’re actually going west. New Mexico is a place that keeps coming up, so that’s where I’m hoping. We have a lot of connections there. We don’t want to go to the biggest city that has the most money. We want to go to places where artists are in need of healing. Like Louisville and St. Louis, that are going through uprisings very similar to each other, we want to facilitate a portion of the healing and include more people than those who are intentionally seeking healing through art. We want to be the healing for the people who are risking their lives to be able to fight for what they feel is right.

AB: What is the long-term future that you see for the Healing Walls Project?

AC: For me, it is always to shift the narrative and create systemic change. To change the way we are seeing and placing public art into our communities. To always grow and always hear the people who are the most marginalized and the most silenced. To be a way to impact those communities but also be an amplification of those voices and put them in the spaces where they are going to be the most beneficial.I want to become a resource so that we are not having to reach out, but rather people reach out to us.

Collaborating with the arts organizations in the cities that we are going to is important to me. We want to have already laid a path so that the gatekeeping that Tabin was speaking of is not so prevalent. What we don’t want to happen is that you feel that you are now an artist but you are then told by your own arts community that you are not valid, that your work is not accepted. So we would like to be a part of that connection and aid to the arts community. We want to be the bridge between the artist and the organization. We want to be able to advise organizations on how better to support BIPOC artists so that we are not just going into a city and then just leaving.

AB: What are ways that people outside of the community served by the Healing Walls Project can support the organization?

Michelle Johnson: We have a GoFundMe campaign and we accept donations through CashApp, Venmo, and PayPal. All of the handles for those are “healingwallsproject.” We are also always looking for people to invite artists who they know; even if they do so recreationally. You can also support us by sponsoring a wall; there are plenty of businesses who would love to have public art and murals in their space but they cannot afford it.

AC: I want to push that this is a Black-owned business. We are looking for resources; that is where we are suffering. One mural can cost $30,000, but our murals don’t cost that because we are teaching and learning through the process. It’s very important that we be supported by communities, we cannot do this without resources. We’re trying to do something radical and when you’re doing something radical and revolutionary, it takes time.

We are paying artists what they deserve to be paid. We are trying our very hardest to teach, provide opportunities, and healing. Resources don’t always need to be in the form of money. You might know how we can get some scaffolding, or paint, or catering. Or maybe you know a wall that is a beautiful wall and everything can be paid for. There’s all kinds of ways that we can be a part of the change and sometimes the people who think that they don’t have anything to give have the most to offer.

The program is specifically for BIPOC artists and a lot of times there have been white muralists that will just put up a mural of a Black face and think that they have given to our community. But what they have actually done is silenced artists. You have given beautiful art and you have taken the time to make that art and it’s appreciated but the more appropriate way is to help, to teach, to give your resources. What our mentors have is knowledge. What they’re giving is so valuable. It’s way more valuable than just putting your art up.

-

Notes:

-

5.29.21

Anna Blake (she/her) is an independent curator and writer. She is a recent graduate of the University of Louisville, where she earned her MA in Critical & Curatorial Studies.

Ashley Cathey, Founder & CEO

Michelle Johnson, CFO

Tabin Ibershoff, PRO & Artist Engangement

Artists at From Spark to the Streets, held February 26-28, 2021 at Artspace

Artist working on a mural organized by Healing Walls Project

Event organized by Healing Walls Project

Artists working on a mural organized by Healing Walls Project