PHOTO: Courtesy of the artist.

Composition series (2018).

Composition series (2018).

︎ Swanson Contemporary, Louisville

History Abridged

Benjamin Cook’s most recent body of work, currently on display at Swanson Contemporary in an exhibition entitled History Abridged, can be framed as a kind of screen art. There are, however, no monitors, televisions, or tablets in the gallery. Rather, Cook’s paintings and drawings—rendered on panel, canvas, or paper—at once allude to and imitate screens, stressing connections between physical and digital realms. More specifically, History Abridged contains an assortment of images that conjure the fleeting qualities of the Internet and the ways in which online engagement impacts experience, at times subconsciously.

Take for example any of the acrylic paintings arranged in a three-by-five grid of panels: each features airbrushed doodles of popular imagery ruptured by thin, multicolored streaks that seem to slowly creep across the surfaces, or in some cases link to themselves, notably as pretzel-shapes in Control the Weather (2018). Among the airbrushed components are items some viewers will recognize, such as a coffee mug, tic-tac-toe diagram, and skull. There are also other more precise—if not esoteric—denotations to pop culture that are, for some viewers, accessible only via digital devices, including Snoopy from the Peanuts cartoons, a Cincinnati Bengals football helmet, and a Bitcoin icon. The doodles overlap and intertwine, and are recorded in varying degrees of transparency—determining which are more present and grounded than others can be an arduous, and perhaps trivial, task. Paintings like Control the Weather are intent on describing the sensation of a constant convergence of tangible space and online activity as well as the vacuum of key parts from both spheres that such a convergence generates.

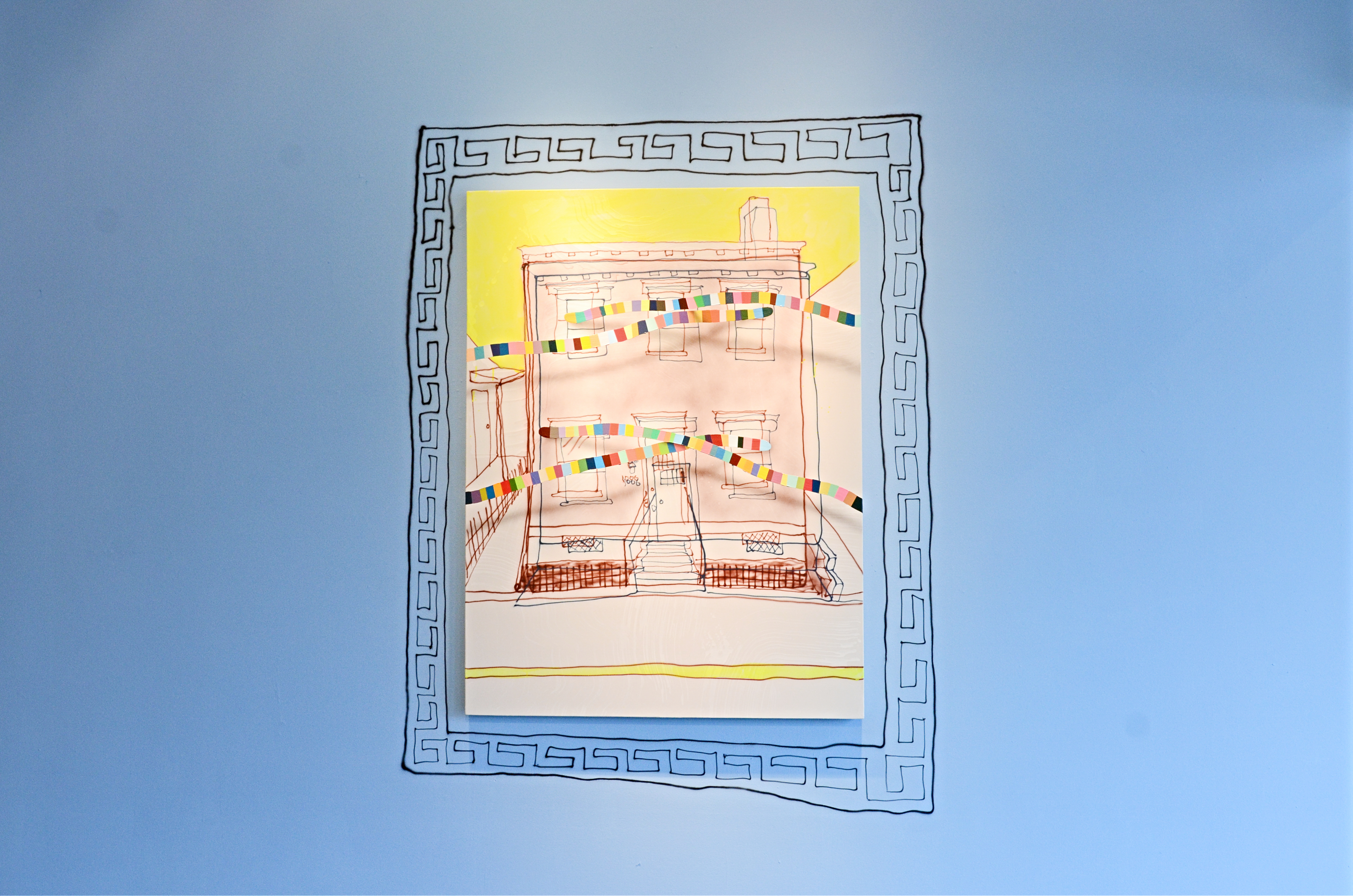

The simulation of a digital experience is amplified by the multicolored streaks, an overt theme throughout History Abridged that provides a distancing filter over faux depictions of an ancient column and laurel leaves in Golden Platform (2018). Four streaks extend diagonally across the painting, and each are accompanied by shadows of themselves, lifting them from the rest of the image onto a plane all their own. Whereas Cook’s airbrush work is frequently blurred and executed using muted colors, his streaks offer a crisp, saturated, and palpable visual contrast, effectively establishing an obstacle between the viewer and familiar iconography. Within the exhibition, the streaks are a prominent indicator of the implicit screen and, arguably, a metaphor for it, as their shadows designate a heightened veneer under which all else occupies. Indeed, the streaks are crucial to this body of work, noted by Cook’s Composition series (2018), where the artist has isolated them using small pieces of felt instead of paint, exercising their applicability as critical tools.

To erode the divide between the physical and digital, Cook relies heavily on pop culture imagery and redundancy. Scattered in History Abridged are overt insinuations to global brands, politics, fictional characters, and everyday objects. Cook is hardly the first artist to invoke such material to address pressing issues; his practice holds connections to a multitude of artists, including Andy Warhol. Warhol repeats a singular image of figures like Jackie Kennedy or Marilyn Monroe onto a single canvas, yet, as Hal Foster argues in the eponymous chapter in Return of the Real (1996), “repetition is not reproduction…repetition serves to screen the real as traumatic,” the real being understood as artistic practice centered on corporeality and shared spaces. In Warhol’s work, imperfect registers, streaking, or dripping in his prints deny direct access to his subjects; instead, offering mediated contact, but still affecting viewers as if they had encountered the actual Kennedy or Monroe (as a traumatic instance, Foster maintains). Cook’s paintings and drawings function similarly. His reuse and repetition of certain emblems are not meant to be taken as replicas, instead the techniques he employs to portray and shade them—including airbrush and hard-lined painting—inspire sensations at which point digital behavior becomes lived experience.

Repetition is at the fore in The Good, Bad, and Forgotten (2018), a line painting of what may be a shared, two-story apartment building, airbrushed in a hazy brown. Onlookers are provided with a frontal viewing angle of the building, but the exact nature of the contours can be difficult to decipher. Cook has doubled the illustration of the structure, yet the paired lines of the same building are dissimilar and wobbly. The windows, staircase, and chimney are unsettled and not wholly stable, much like Warhol’s figures. The subject of the work describes a communal site—an anchor for those who populate its interior. Here, the repetition of the building is a screen, and the imperfect lines help to further distance it from the viewer. Repetition and technique combine to impact viewers as Cook intends—in this case, with impressions seemingly of home and memory.

Four streaks and their shadows emerge from either side of The Good, Bad, and Forgotten, arising in two slightly different formations wherein a single streak nears another, in one case making an “x” shape. Streaks again form a layer separate from the building by serving as the screen, an effect bolstered by wavy brush marks that Cook states “act as greasy fingerprints.” For Foster, the purpose of the screen, a barrier between viewer and subject matter, is “to negotiate a laying down of the gaze as in a laying down of a weapon.” Fosters leans on Jacques Lacan’s iteration of the gaze, which Lacan describes as the awareness of being able to see and be seen, sparking feelings of vulnerability. While imitating and simulating screens, Cook’s artworks in History Abridged also simulate the disarming powers of the screen. Viewers are vulnerable to the screen’s mesmerizing qualities and content; Cook’s selected iconography suggests that screens can become effective weapons to enact influence over others.

Screens are, by their nature, democratizing social tools. With them, information is widely dispersed and easily accessed. In History Abridged, Cook insinuates this quality of digital devices by creating frames and pedestals—usually mimicking classical traditions—airbrushing them directly onto the gallery walls. For instance, The Good, Bad, and Forgotten is encompassed by an ornate painted Greek Key frame. Round and Round (2018), a sporadic arrangement of airbrushed emojis, sports references, and potted plants behind whirling streaks, is hung so that is appears to sit atop a Greco-Roman column. The manner in which these pedestals and frames exist, as representations rather than physical or accurate objects, are democratizing in themselves. Recalling the exhibition’s title, they ask what is worth remembering, what is actually committed to memory, and to what degree history is a personal or social venture (or both).

In History Abridged, Cook challenges viewers’ perceptive abilities. On one hand, he tests how many elements of pop culture and daily life they may or may not recognize. On the other, he constructs the illusion of looking at screens, demonstrating the extent of his illusory skills with a pair of trompe l’oeil paintings of sketches on scratch paper. Cook is also interested in how history is perceived, and whether the impetus of history rests more in personal, bite-sized, sometimes mundane moments or in widespread narratives of grandeur heroics and epic downfalls. History Abridged does not necessarily provide an answer, but the ways in which it steers away from traditional painting techniques and embraces the likes of beer cans, skateboard ramps, and CatDog, implies that perhaps history is what we choose to make it.

-

History Abridged is on display at Swanson Contemporary through September 22.

Swanson Contemporary is located at 638 E Market, Louisville, Kentucky, 40202 and open Wednesday through Saturday from 12-5pm.

Notes:

- Swanson Contemporary

- Benjamin Cook

- Foster, Hal. “The Return of the Real.” In Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century. Cambridge, MA and London, England: The MIT Press, 1996.

Hunter Kissel, Guest Contributor to Ruckus

9.8.18

Install.

Control the Weather (2018). Courtesy of the artist.

Golden Platform, install (2018).

The Good, Bad, and Forgotten (2018). Courtesy of the artist.

Install.

Blink (blue) (2018).

Courtesy of the artist.