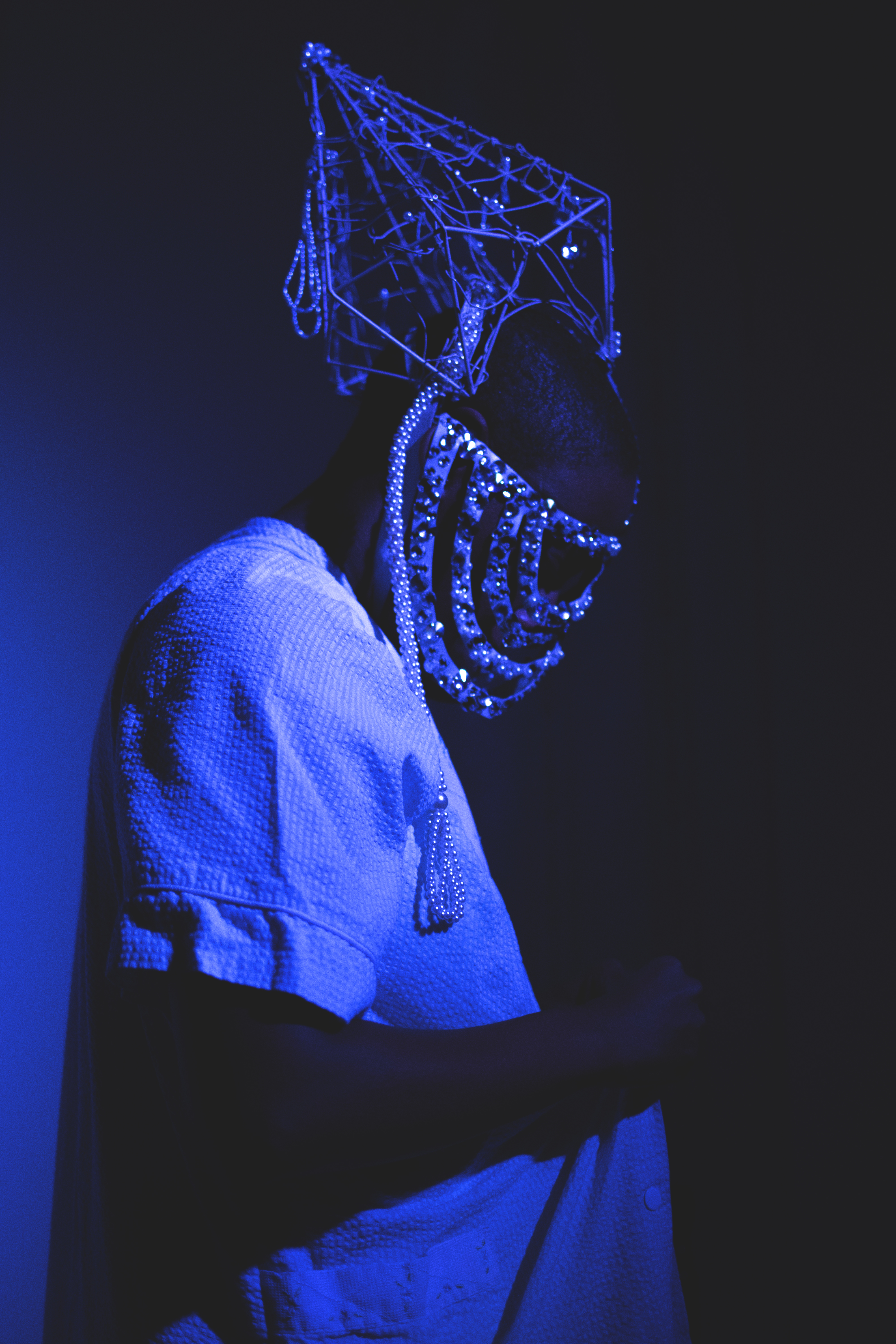

Above and Below: Jennifer Harge performing as nyeusi in FLY|DROWN. All the photos are courtesy of Devin Drake.

︎ Detroit

Jennifer Harge

Q&A

Gervais Marsh

This is an interview between artist Jennifer Harge and writer Gervais Marsh, focusing on Harge’s latest performance and film project FLY | DROWN. Harge and Marsh have been friends for the last several years, after meeting at the New Waves Performance Institute in Trinidad and Tobago. The conversation interweaves thinking about Black people’s creation and negotiation of domestic space, Black femme societal experiences and embodiment, conceptions of queerness and the possibilities for Black life amidst an anti-Black world.

Jennifer Harge is an interdisciplinary choreographer, performance artist, and educator based in Detroit, MI. Her work centers Black and queer vernacular movement practices, codes, and rituals that manifest at the intersections of performance, installation, and community gathering. Harge’s processes and artistic products grow out of Black subjectivity; Black feminist thought; nurturance of intimate reciprocal partnerships; and iteration-based research that allows the work to evolve nomadically across time and varied contexts. She founded Harge Dance Stories in 2014 as a container for choreographic research.

-

FLY | DROWN is a dance folktale honoring Black women’s movement towards flight. Set in a post-Great Migration home in Detroit, MI, it is an interwoven story of two characters, elder and nyeusi, and moves between the mundane, the majestic, fact, and fable. nyeusi, a Sankofa bird from the river, and elder’s child from another lifetime, has been conjured into the home to teach elder how to remove the shame in her body in order to fly. The performance platforms the interiority of Black women’s lives and Black aesthetic making to trace corporeal and material cartographies used to obtain a Black freedom(s). The home is a site to consider how Black women renegotiate their edges, rename themselves, and expand the capacity of their breathing.

FLY | DROWN has taken different forms over the last several years, from a live performance and now a series of films. It is a collaborative project with curator Taylor Renee Aldridge, producer Nadia Tykulsker, media designer and filmmaker Devin Drake, and sound designer Sterling Toles.

View FLY|DROWN Trailer: https://vimeo.com/507148346

The Fly|Drown Fables currently on view at Wexner Center for the Arts: https://wexarts.org/exhibitions/jennifer-harge-devin-drake

-

Gervais Marsh: What are some of the words, phrases, gestures, sounds, images, and figures you were meditating with while conceptualizing FLY | DROWN, and that you continue to return to as the piece grows and takes different shapes?

Jennifer Harge: To steal oneself away is a phrase. Breathing air, establishing flight, movement and performance within the zone of blackness. I grew up in such a tangled space with not just Western dance, but like Western dance value systems. How I understood how to make work, how to have a produced work, the values around how folks should interact with that work. It always felt tight to me. When I got into high school, I was like, something doesn't feel right. And I think for years, I have been trying to think about making it my own way. And then I would say around New Waves time [a performance institute in Trinidad and Tobago], I was just like, I actually have to get out. I need to go dance and move in a Black country. That was the only thing I knew. Like I just need to move outside of a U.S. context. I was saying things like, “I want to empty all the white inside of my body.” What is that even trying to do? Replace it, or something. Not as a new way in particular, but how can I reorient myself towards another direction? How do I steal myself away as a return to myself?

The score that you and I made [I visited Jennifer at her residency with the Museum of Contemporary Art-Chicago] was really the beginning of that. It was when Blackpentecostal Breath (text by Ashon Crawley) had just come out and everyone was talking about the otherwise, and I was with it. I was like, wait, but then where do I land though? What are you gonna do after you leave? So the score, it says, breathing air establishes flight. Then in the corner, just a little citation. Can you read that at the top, the little box? (“citing Gervais Marsh” written in the corner).

GM: Listen. Oh, my God, we've been talking about this for a long time.

JH: We were talking about excess. Gasping was the word, and openness, softness as responses to fugitivity. So FLY | DROWN is using this great migration in the home like that. The migration is the route and then the home is the landing. It's one way we Black folks have made a place after the escape. When I leave, where will I land? How will I land? What do I need? Who needs to be there? How do I enunciate all of that? The path and the landing?

Those were the opening questions.

I was also trying to figure out how to walk on the sky for a long time. I am thinking about how to anticipate things, and what is an anticipatory movement? I learned a lot about that when I was at a residency in the Redwood Mountains. The actual residency space is on top of a mountain, so the birds and the sky are very close to you. I would watch the birds all the time, how much they anticipate the wind, and how they catch it. And then you just ride it and I ended up using gospel music. Primarily Aretha Franklin, specifically thinking about how to ride her ad libs.

GM: Wow! There’s so much here. That imagery and way of thinking about that relationship—riding Aretha Franklin’s ad libs is something that I just love! For me I think of ad libs as this space where you do what you want. And to take and make your own.

JH: It’s this space for her to really break. I talked about breaking a lot while developing the work, like how to find the break, and what opens up for you. When the thing does break, you have to find a recovery in some way. Thinking about what are the ad libs for Black folks, maybe it’s the flex.

GM: Are there other ways that you were thinking about the soundscape and the relationship between the soundscape, your movements and gestures, and talking about it with your collaborators?

JH: Yes. So I went into this project with Sterling Toles (sound artist and healer) thinking that we'll be creating a lot of new sounds together based on the research. But actually, all the sounds that I was thinking about—the themes that I was living with—Sterling had them in his vault like, it was just kind of already alive. There were already sounds that he had created years or a decade prior. And one thing about Sterling: he will describe himself as a healer through sound versus like a sound designer, and he is really gracious about energy. And I think that is one place where my practice is too, being with energy, protecting energy, pushing energy. If it doesn’t serve the thing, pushing it out.

Devin Drake (filmmaker) and I have made, for this last film, iterations of energy mapping and how to track it. How to bring it down to a sound rate. So I think Sterling and my practices, and, our listening, comes from listening to the energy in Detroit. It's sort of energy that when people ask about it, I don't know how to describe it to you. You just gotta kind of come, you gotta feel it and then, you tell me what that is for you. Your relationship to that. It's visceral and I think music is very visceral.

GM: How are you thinking about the domestic space and the relationship to Black femme interiority? There's layers to it: Black femmes being tasked with making and maintaining the domestic space, but also having to grapple with these difficulties and violence in the domestic space, and how to make sense of that. I mean, you can't make sense, you know, maybe there's no making sense of it. There's so much intimacy in that and the space is so charged.

JH: So I’ll say one thing about the mask as it related to the space in the development, because that was a very late addition. It wasn't part of it at first, but I know the mask came in for me to create a little distance between just seeing me as a person in domestic space, so I wasn't becoming this mammy for the audience. Making the characters otherworldly is a way to fulfill them, create some distance. Like we are in a familiar space, so this character blurs the line a little bit and lets me be with the materials in the space in a way that I didn't have to tend to my own memories.

The folk tale is that nyeusi comes into the home or into the elder's subconscious. It could be both. nyeusi came to teach her how to release the shame of her body in order to learn. Because I think that’s how it feels for me, moving energy out. Yes, I know this has been how you've been in your life, but there is another way. There is this otherwise, if you will.

There are always histories in the home, and the more people who go in and out, the more stuff that happens there, always so many histories. I'm learning from it, too. How to just enter and think about how we can work together to think about how to do something differently, it's a hard space to shift.

GM: Anything else about the garments that you felt was important to explore? There's this simplicity and elegance, and I am thinking about the masks and the gown as ways of distinguishing between the characters.

JH: I think I'm a really bad costume designer. I didn't have costumes because I didn't think about it until the point that I'm like, well I need something to wear. I had that gown from a previous piece that I found in a second-hand store, and I saw it and knew I needed it. I'm also feeling a lot of energy around this question right now because I lost the gown. I also lost Beloved (Toni Morrison’s novel), so I keep losing things. Something in me feels like I'm getting to the place where I need someone to make the garments for these characters.

GM: I have a question about Beloved, because that also came up when my friend Candice watched FLY | DROWN with me. We started talking about it and now I'm thinking, did Beloved, the spirit, take the gown and take the book?

JH: I don't know because in the studio that we were in, most of the filming happened either at the river or in the backyard. I would read out there a lot. Did I bury it by accident? It's just like a lot of trickery beginning to happen.

GM: Yes, maybe Beloved did take it. People didn’t really think of Beloved as a good spirit. But also Seethe had a particular kind of relationship with Beloved, this intimacy and this idea that Beloved is her best self, you know, like it's part of her in that way. Then I started thinking about Sula (Toni Morrison’s novel) because of nyeusi’s relationship with elder and I’m wondering, is that what Sula in some ways was doing for Nel? That's also complicated. Then I started thinking about Song of Solomon (Toni Morrison’s novel), and flying, searching for that release. It feels like all these texts are woven into the piece, but maybe I’m making that up. Are you thinking with these texts?

JH: So I didn't read Beloved during the making of FLY | DROWN, so for me it was like we're making a Beloved story that is my own beloved story. I was kind of aware but it wasn't really explicit for myself. I was like, ride the wave of this creative process and distance myself from that specific text. Another idea, thinking about flying in like the mending way that Toni Morrison does, you know, really fantastical. But I do think this is totally a Tony Morrison project.

GM: So that's why for me it feels like this piece is interweaving the different texts because that's also the way that Morrison does it. The text never comes to a conclusion, there's never one answer that it gestures towards.

JH: Yes, and I was looking at this score that you and I made and it says something about being a disruption. Oh, “breathe within the zone of blackness,” and it says this will be a disruptive force, or a relieving force. And it's always that kind of time.

GM: I remember when I saw you teaching at University of Michigan, and you were talking to the students about Christina Sharpe’s conception of the weather (from the text In the Wake), and thinking about anti-blackness as a weather condition, and how do you navigate that? I was also thinking about Christina Sharpe discussing keeping breath in the Black body and she proposes aspiration as one way to think about this. There's a connection both in terms of breathing, but also reaching towards something. Maybe it's opening up your view, a different orientation towards things. I'm trying to hold this relationship between flying and drowning, but also between breathing and submersion, and submersion as a way to expand your breathing capacity. To learn new techniques to breathe and you have Alexis Pauline Gumbs at the end of the piece talking about it.

JH: Yes, from M Archive (text by Alexis Pauline Gumbs).

GM: How are you thinking about submersion and breathing, and what does it look like to keep breath in the Black body? Because I think it has to look like a lot of things.

JH: The one thing I’m thinking about right now as I'm listening to you is stillness. How to be at a restful breath. And I think the submersion for me was always a portal into something. I think that's true, it is what elder is aspiring towards, but she's wearing ankle weights so there's obviously barriers to that. I think that nyeusi was like a way to disrupt the breathing that was happening to show elder that she is just pretending that she is breathing normally, pretending that you can survive anti-black weather. But like none of us can. And so I think, like, it was a requirement, the submerging. We don't start over. We don't just go back and then come out of it.

GM: Ok moving forward a bit, there's this intimacy between nyeusi and elder, and there's a queerness to the ways they're relating to each other, moving around each other, and it's making me think about queerness as intimacy, and also queerness as a way of thinking about more expansive ways that you can be in your body. I'm just interested in how you were thinking about queerness in the piece and its relationship to them, if at all? Maybe you're calling it something else.

JH: This is a great question. So I feel like it was something that was always really felt but I never articulated it. I'm thinking about the moment when nyeusi is doing a hand game and that kind of touch and how it feels to touch the silk and just rest the palms, what will presumably be elder's knees, if there was a body inside of the gown. How nyeusi would have to be looking into elder's eyes, there's a softness, and there's a notion of the spirit, to be held. And queering the spaces, knowing that there is more. There are other breathing possibilities that can happen right where you are. That is how I understand queerness, it is an opening of possibility.

GM: Do you feel like there were any kinds of gestures, because I've been thinking about ritual and repetition, and how those flow into each other. So are there gestures that are forms of Black feminist knowledge?

JH: So I'm looking over right now, and then this one book is right here (Enunciated Life catalog, exhibition curated by Taylor Renee Aldridge at California African American Museum). I feel like enunciation was a gesture in developing nyeusi, like I can't even do it right now (Jennifer moves her body in ways similar to her performance). I was like oh, you really were conjuring that character with all the joints necessary to articulate her. There is something in each vertebrae, to enunciate.

GM: Yeah, that's a helpful way to think about it, it's an enunciation. To close out this conversation, I just want to hold space for the idea and experience of collaboration and what it has meant for you to collaborate with Sterling and Devin, with Taylor, and what collaboration means in the creation of this work, and its different iterations.

JH: You know, I thought about this yesterday actually, what collaboration has taught me and the people you just named, those three especially, have so many gifts. Just the most generous, yeah, generous is the first word. So like, deeply spiritual in vastly different ways, teaching me to be surrounded by the many ways we can be. The things that they have offered to this project is just like the breath of themselves. These are creative people and they offered their gifts to this project, this world, and in that, they have allowed me to understand that I can do more than just be a dancer, because I am more. I've learned the magnitude of Black creativity. Just trusting in us, being with your people and having a collective understanding and then giving folks space to just join in and they get in where they fit in. So I approach folks as creative people. I've learned that from being collaborative, sharing with these people. Oh, you make me emotional.

GM: Me too, I feel like, shall we stop there? I'm just grateful for this conversation.

JH: Oh, I'm so grateful, thank you. I'm so happy with the first question, because then it brought us back to our scores together. Such beautiful questions, and just really helpful.

GM: I deeply appreciate you.

-

7.15.22

Gervais Marsh (they/them) is a writer, scholar and curator whose work is deeply invested in Black life, concepts of relationality and care and rooted in Transnational Black feminist theory and praxis. They are a PhD candidate in Performance Studies at Northwestern University and their writing has been published in ARTS.BLACK, Musée Magazine, Sugarcane Magazine and PREE: Caribbean Writing, among others. They are an editor with Ruckus Journal and recent curatorial projects include Heather Brammeier’s Maybe Never and A.J. McClenon’s Notes from VEGA at the Hyde Park Art Center. They grew up in Kingston, Jamaica, a home that continues to shape their understanding of self and relationship to the world. To learn more about their work please visit https://www.gervaismarsh.com/.

7.15.22

Gervais Marsh (they/them) is a writer, scholar and curator whose work is deeply invested in Black life, concepts of relationality and care and rooted in Transnational Black feminist theory and praxis. They are a PhD candidate in Performance Studies at Northwestern University and their writing has been published in ARTS.BLACK, Musée Magazine, Sugarcane Magazine and PREE: Caribbean Writing, among others. They are an editor with Ruckus Journal and recent curatorial projects include Heather Brammeier’s Maybe Never and A.J. McClenon’s Notes from VEGA at the Hyde Park Art Center. They grew up in Kingston, Jamaica, a home that continues to shape their understanding of self and relationship to the world. To learn more about their work please visit https://www.gervaismarsh.com/.