Above: Install of Loose Nuts: Bert Hurley’s West End Story

︎ Speed Art Museum, Louisville

Loose Nuts: Bert Hurley’s West End Story

Review

L Autumn Gnadinger

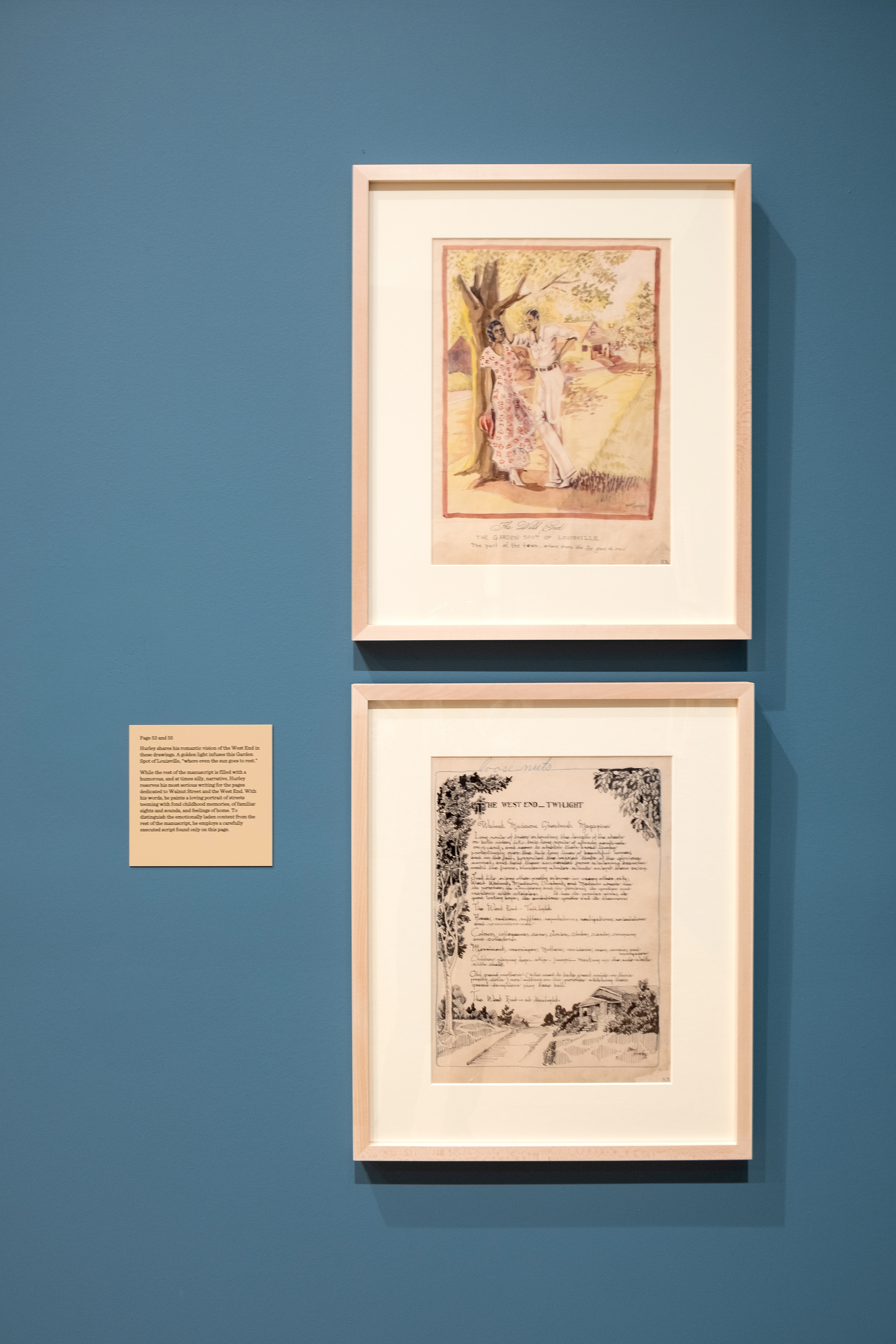

If you are willing to venture: head across the Speed Art Museum’s original atrium, pass through the first few wings of oil paintings, go up the stairs above the cinema and you’ll finally arrive at Loose Nuts: Bert Hurley’s West End Story. On the way, you will, of course, notice elegant marble busts, the large Jordaens the Elder, and the quieter Rembrandt etchings. The extra travel time through the encyclopedic section lends a bit of gravitas to Bert Hurley’s graphic novella Loose Nuts: A Rapsody in Brown, which is on display for the first time since its creation in 1933. The improbable 128-page hand-drawn manuscript is exciting to see exhibited on its own merits (in some ways, what you see is what you get), but the show is fully realized when considered in its contemporary context. Loose Nuts feels essential ninety years later as a hybrid archive and aesthetic gesture.

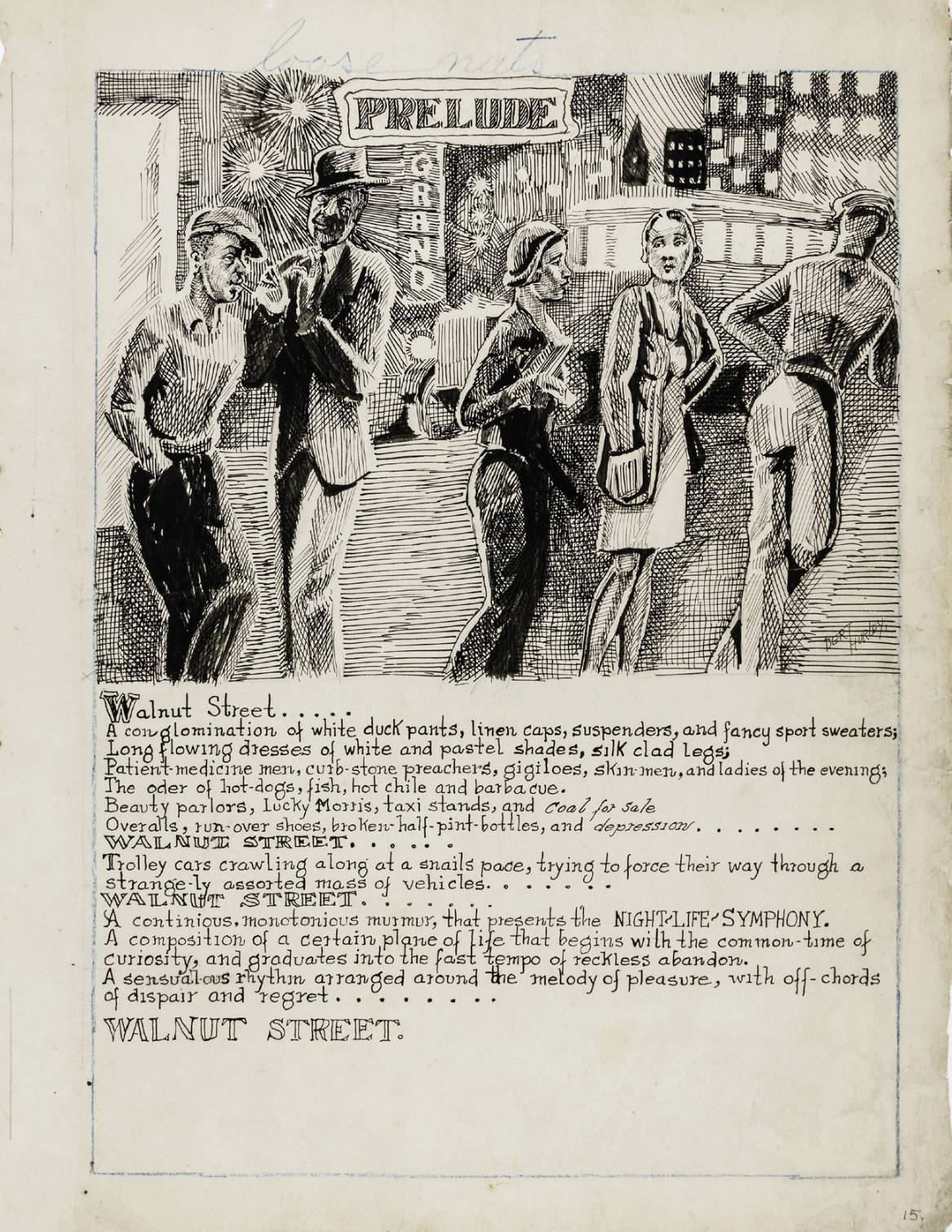

A Rapsody in Brown is completely comprised of hand-drawn text and illustrations which tell a semiautobiographical story of its author, Bert Hurley, solving a crime-mystery in a bombastic and intentionally playful reportage style (perhaps drawing on his own experience contributing to the Employees’ Magazine for the Louisville & Nashville Railroad Company where he worked for forty years). On page 49 of the manuscript, Hurley announces “Dear Readers: our story now carries us to the western part of Louisville. Come go with us to the WEST END.” The remainder of A Rapsody in Brown could only be described as a love letter to this home and community during the ’30s. Hurley described it at various points as “The garden spot of Louisville,” home to the “horticultural at the zenith of perfection;” full of parties and “gorgeously gowned ladies.”

The images are built in a variety of media (what seems to be pens, colored pencils, inks, and washes) and the illustrative style shifts from page to page: hard cross-hatched lines on page 15 might become gentle watercolor by page 59. These differences might be intended to follow narrative fluctuations in tone, but given the sheer amount of hand-written text, one also gets the feeling that Hurley’s interest in rendering images was just changing over the length of time it must have taken to create Loose Nuts. For the exhibition, the pages have been carefully isolated from their original staple binding and presented across the space in attractive wood frames. This invites a reading of the sheets as discrete works in and of themselves but does not stray far from the presentation styling of the encyclopedic section of the Speed (viewable just through the exit of the Loft Gallery).

Still, in the backdrop of longstanding trends in contemporary art that deal with text-supplemented content (Chitra Ganesh, Ed Ruscha, or Jenny Holzer, to name a few) and the manipulation of both real and imaginative archives, it is difficult not to consider this work as contemporary. Aside from being lost to history for much of the last century, it feels unmoored between this moment and the adjacent wings that house works of 19th-century French lithography—Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec's "Polin" (1898), and Louis Auguste Mathieu Legrand's "Act 3, Scene 8, Part 4 of Something or Other" (1893), stand out in this way—in a similar merging of illustrative style and hand-drawn text.

Loose Nuts draws its potency from a likeness to both the old and new. Theorist and historian Hal Foster describes a function of the tendency to reference and use archives in contemporary work and curation in the following way: “these private archives question public ones: they can be seen as perverse schemes that disturb (if only slightly) the symbolic order at large. On the other hand, they also point to a possible crisis in this order or, again, to an important change in its workings.” By exhibiting Hurley’s work right now, with its earnest levity and depictions of a lively and festive West End through a crucially nonwhite perspective, A Rapsody in Brown further disturbs an already-shifting understanding of Louisville’s own history. The Speed Art Museum has done an excellent job of including appropriately complex supplemental information (like images and descriptions of Black-own business districts, or notes on the history of racist real estate redlining in Louisville and the subsequent impact on the shape and economics of the city we see today) without fully distracting from Hurley and the intrigue of his work and life.

While it is possible to view the entire story from beginning to end on a digital display in the gallery, or for free on the Speed’s website, it would be cumbersome to read the entire book during a single visit. The takeaway from Loose Nuts, instead, becomes just a blur of Hurley’s own memories—real and imaginary—of a West End that certainly may have been, but is no longer. There is, to be sure, no shortage of contemporary affection for the neighborhoods that Hurley wrote about. Similarly, there remain impressive and important businesses run by and mostly for Black people in Louisville. Still, the sense of grandeur with which Hurley depicted this time is now harder to find. Viewed today, the story becomes more like what would become known as Afrofuturist—despite calling to us from the past, as an alternate timeline produced by a loving Black gaze (Dery, Tate, 1994).

To have never heard of Bert Hurley is, regrettably, almost a guarantee. Between this and the inevitable economic fate of the mentioned Walnut, Madison, Chestnut, or Magazine Streets at the hands of cruel city policies and a racist white population, there is a eulogistic quality and equal sadness in viewing this work. Perhaps the poet Nancy Shores, whose words Hurley includes at the end of Loose Nuts, points at this best: “Perhaps it is because we grow older, that we magnify the past; perhaps our eyes were clearer then and we itemized the treasure more skillfully...They are playing now, the children of yesterday; tomorrow they will remember the curve of the new moon, the scent of petunias at twilight, and the river swelling in the sun as part of the glamour that spread around them in one golden long ago summer.”

-

Loose Nuts: Bert Hurley’s West End Story is on display in the Loft Gallery of the Speed Art Museum through April 19, 2020. The Speed is located at 2035 S 3rd St, Louisville, KY 40208, and is open Wednesday-Sunday with variable hours.

-

Notes:

- Foster, Hal. Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, Emergency. London: Verso, 2015.

- Read all of Loose Nuts: A Rapsody in Brown for free on the Speed Art Museum’s Website

- Dery, Mark. Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose. Durham and London. Duke University Press. 1994.

- Redlining Louisville: Racial Capitalism and Real Estate

-

L Autumn Gnadinger

Print and Digital Media Editor, Contributor

12.23.19

Bert Hurley, Loose Nuts: A Rapsody in Brown, cover, (1933), Pen and black ink, brush and black ink, crayon, watercolor, and graphite on wove paper. All scans courtesy of The Speed Art Museum.

Bert Hurley, Loose Nuts: A Rapsody in Brown, page 15, (1933), Pen and black ink, brush and black ink, crayon, watercolor, and graphite on wove paper. All scans courtesy of The Speed Art Museum.

Bert Hurley, Loose Nuts: A Rapsody in Brown, page 25, (1933), Pen and black ink, brush and black ink, crayon, watercolor, and graphite on wove paper. All scans courtesy of The Speed Art Museum.

Bert Hurley, Loose Nuts: A Rapsody in Brown, page 58-59, (1933), Pen and black ink, brush and black ink, crayon, watercolor, and graphite on wove paper. All scans courtesy of the Speed Art Museum.

Bert Hurley, Loose Nuts: A Rapsody in Brown, page 53 & 55, (1933), Pen and black ink, brush and black ink, crayon, watercolor, and graphite on wove paper.