Above: The house where James Baldwin lived and died in Saint Paul de Vence, France, July 2009. Wikimedia Commons.

Out of the Shadows: The Queer Life of Artist Beauford Delaney

Essay

Tyra A. Seals

This story was originally published by Scalawag, a journalism and storytelling organization that illuminates dissent, unsettles dominant narratives, pursues justice and liberation, and stands in solidarity with marginalized people and communities in the South.

This story was originally published by Scalawag, a journalism and storytelling organization that illuminates dissent, unsettles dominant narratives, pursues justice and liberation, and stands in solidarity with marginalized people and communities in the South.

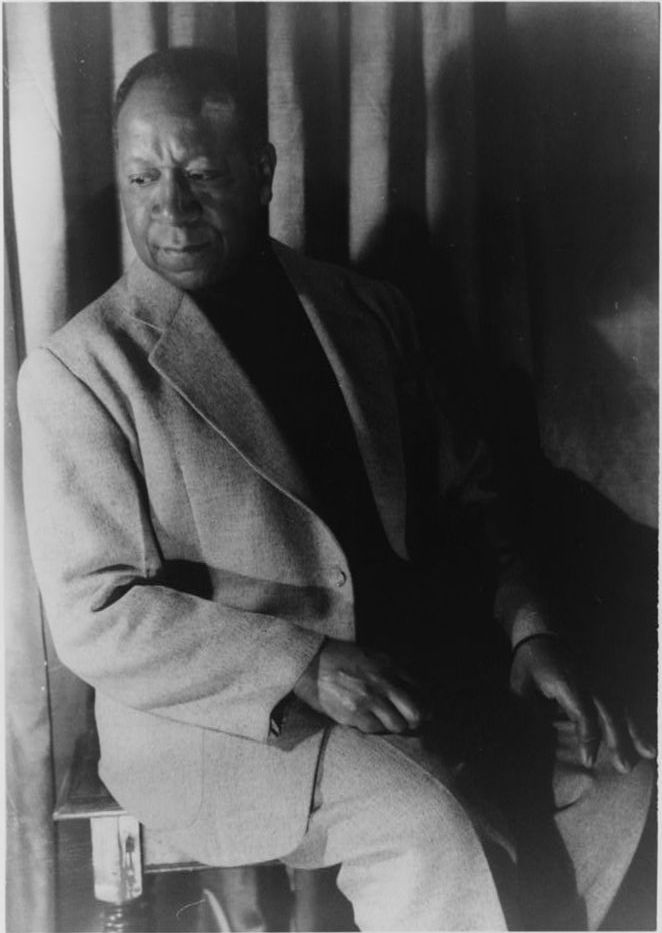

"Beauford was the first walking, living proof, for me, that a black man could be an artist. In a warmer time, a less blasphemous place, he would have been recognized as my Master and I as his Pupil."

— James Baldwin, on Black, queer artist Beauford Delaney's impact in his 1985 essay collection, "The Price of the Ticket."

It's difficult to imagine one of Picasso's villas falling into disrepair, or the four-story mansion of Andy Warhol knowingly demolished.

Yet, in 2014, that's exactly what happened to the final home of James Baldwin. Despite widespread fundraising efforts to curtail its destruction, a luxury condo developer bulldozed two wings of the cottage in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France, where the literary legend spent his final 17 years.

There's a long history of disregarding and discarding Black artists late in life—with record upon record of institutional failures to support the very people who've shaped our culture and preserve their legacies after they're gone.

Some 500 miles north of Saint-Paul-de-Vence, about nine years before developers demolished Baldwin's cottage, a group of Black patrons in Paris launched a fundraising campaign to create a proper tombstone for the writer's mentor, the once-renowned abstract expressionist painter Beauford Delaney.

One of the pillars of the Harlem Renaissance, Delaney rose to prominence in New York City in the 1930s and '40s before moving to Paris, where his energetic use of color and mastery of portraiture would secure his position as one of the most influential American artists of his time. Portraited by Georgia O'Keeffe, revered by Willem de Kooning, Countee Cullen, Baldwin, and so many more—Delaney ought to be a household name right alongside Picasso and Warhol.

But after decades of living in poverty, struggling with alcohol to cope with the hardships and horrors of being an openly gay Black man from the South, Delaney's mental health rapidly declined towards his latter years. In 1975, when his friends could no longer provide daily care for him, he was committed to Sainte-Anne Psychiatric Hospital in Paris, where he died in 1979, at the age of 77. Although his obituary appeared in The New York Times, his work fell into relative obscurity after his death.

Located on the sprawling grounds of the 400-year-old asylum, the unmarked gravesite of the Tennessee-born artist was in danger of being erased forever.

It's only because of those who loved Delaney, then and now, that his legacy survives. And there's much for us to learn from this legacy.

There's so much for us to learn about this queer Black artist who battled addiction, mental health crises, homophobia, and anti-Blackness, yet produced joyfully expressive experiments in color and form. His identity and his work speak to people today looking for a safe haven within which to create and thrive. Delaney deserves to be celebrated everywhere—not only in the halls of the Met and the Musée d'Orsay, but also within our Southern region. It is that need to recognize his impact that's inspiring Black cultural workers around the globe to carve out more safe havens in his name.

. . .

Beauford Delaney was born in Tennessee on December 30, 1901, and grew up on Knoxville's East Vine Avenue. The Delaney home was located within a lively Black American business district during the first half of the 20th century, very close to the historic Free Colored Library of Knoxville and the Gem Theatre. Poet Nikki Giovanni, who became a neighbor to the artist's mother Delia Delaney years later, describes the area in her essay "400 Mulvaney Street":

Mulvaney Street looked like a camel's back with both humps bulging—up and down—and we lived in the down part. At the top of the left hill a lady made ice balls and would mix the flavors for you for just a nickel. Across the street from her was the negro center, where the guys played indoor basketball and the little kids went for stories and nap time.

Delaney was drawn to art from an early age, first copying pictures from the family Bible and later working as a sign-post painter in his teenage years. However, as the eighth of the ten children born to Reverend John Samuel and Delia Delaney—and only one of four to live to adulthood—one could imagine the social pressure placed on young Beauford.

Additionally, his early recognition of his queerness made life under the dual forces of Jim Crow and his father's religious scrutiny untenable. Delaney eventually moved to Boston in 1924 to study art, and then to New York five years later where he could live openly as a gay Black man while developing his particular stylistic approach.

Delaney's colorful urban landscapes and expressive portraits secured him a name in prominent artistic circles during the height of the Harlem Renaissance. His insistence on invoking brightness and warmth into every scene is echoed through this 1951 painting of Washington Square Park. A jubilant yellow foregrounds the canvas and permeates in various places like the color of a woman's hair, the outline of the tree to the far left, and the sun that's placed just between that tree's branches. His use of yellow here and in many of his other landscape paintings of parks is a testament to his buoyant spirit.

This spirit, evident in so many of his works, seemed able to see through the opacities and hardships of life to depict the deep joy at the center. And though Beauford never returned to live in Tennessee, preferring at times cold nights on the park benches of Union Square to a life limited by Jim Crow, Delaney still bore vestiges of his Southern upbringing.

An interaction with prominent Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning illustrates this well: de Kooning, then a friend of Delaney, tried to advise the painter on how to better market his artwork, which did not enjoy much commercial success during his lifetime. Delaney's biographer, David Leeming, records that Delaney rolled his eyes, gently patted him on the shoulder in that characteristically Southern way, and responded "Bless you, child." He would pay de Kooning no mind and go on painting as he always did.

While in New York, Delaney befriended many artists and entertainers, like Ethel Waters and Billy Pierce, ultimately trading the Depression-era landscapes he initially painted for bright, vibrant portraits of those he encountered and cared for deeply. As one of the few Black artists to suffuse Abstract Expressionism's breakthroughs with a Black subjectivity, Delaney occupied important positions within New York's arts scene and its separate gay and Black communities. His works, with their thick, vibrant brushstrokes, expanded the possibilities of how people of color could look and be received on the surface of a canvas.

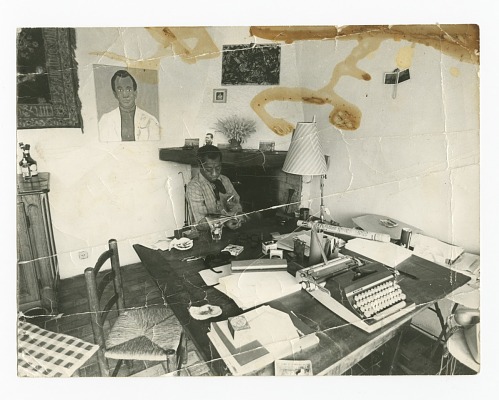

Cherished author and cultural critic James Baldwin was perhaps Beauford's closest friend throughout his adult life, from New York to Paris. Captured in this portrait, Baldwin is surrounded by pastel hues—of which yellow is naturally one. Viewers can feel comforted by the great detail in the calm, poised nature of Baldwin's face and the clothes he wears, reflecting the strength and depth of the two men's relationship.

. . .

Delaney left New York in 1953, then 52 and a respected artist, though he continued to struggle financially. His work found little commercial success at the time, but he continued to push boundaries with his paintings and was eventually noticed by Darthea Speyer. Speyer, who arrived in Paris in 1950 as a cultural envoy for the United States Information Services, ran the American Cultural Center and carefully stewarded Delaney's career. The Center would give many American artists their first European exhibition, including Delaney, who exhibited there throughout the 1960s.

In the invitation card for a 1992 solo exhibition of Beauford's works at Galerie Darthea Speyer nearly 13 years after his death, Speyer speaks fondly of Delaney and recalls his coming almost every day to her office at the American Cultural Center, and then to the gallery. She details how he happily and quickly captured portraits of her loved ones on canvas, and spoke regrettably of the shadow that descended upon his spirit and eventually led to his commitment at Sainte-Anne.

Delaney's mental health decline was challenging and layered. His hallucinations and paranoia were exacerbated by his reliance on alcohol, and undoubtedly from being distanced from his family as a queer Black American man living in Europe during the height of the Civil Rights era. He attempted suicide in 1961 while traveling in Greece.

Through it all, Delaney was surrounded by close friends who he cared for and who cared for him, including Speyer, Baldwin, artists Charles (Charley) Boggs, James (Jim) LeGros, collector Burton Reinfrank, friends Bernard Hassell, Professor Ahmed Bioud, and Madame Solange du Closel—an avid French collector of his work. Brought together by love and friendship, they managed the various details of his estate, becoming legally responsible for his affairs in 1976 as his trusteeship or tutelle. It was clear they cared for Delaney, the man, not just Delaney the artist.

Baldwin's words about Delaney in the Retrospective catalog echo the sentiments of the group: "Perhaps I am so struck by the light in Beauford's paintings because he comes from so much darkness—as I do, as in fact, we all do… And I do not know, nor will any of us ever really know, what kind of strength it was that enabled him to make so dogged and splendid a journey."

. . .

The care demonstrated by Delaney's tutelle carried him through the end of his life, but it alone couldn't secure his legacy in perpetuity. Delaney never returned to the United States and was buried in a pauper's grave in Thiais Cemetery just outside Paris.

Because French graves are temporarily leased and Delaney's had not been renewed since his death, the artist's remains became at risk of exhumation. Again, people who cared for the man beyond the paintings intervened.

In visiting Delaney's gravesite purely "as a favor to friends of his," local researcher Monique Wells quickly learned about the artist's internment in a Parisian suburb, and later, of the beauty of the artworks he created. She never expected an unmarked, hardly recognizable grave of a Black artist to propel her into action for over a decade, but that's exactly what happened. After discovering the unmarked grave in the summer of 2009, Wells began a broader mission to get Delaney his flowers.

In November of that same year, Wells started the organization Les Amis de Beauford Delaney and secured a $5,000 donation from the Knoxville Chapter of The Links, Incorporated, which helped bring Resonance of Form—the first exhibition to display Beauford's works in Paris since 1992—to Knoxville in 2016. A year later, the organization partnered with the Knoxville Museum of Art and launched The Delaney Project. This partnership brought a pilot educational program called "Bringing Beauford Delaney Home" to a school in Knoxville to share Beauford's life with elementary students in his hometown and to awaken their own creative genius.

This community investment is all the more important since the idyllic neighborhood Giovanni described in "400 Mulvaney Street" was eventually undone by urban renewal. The impact of the federal Urban Renewal projects from 1949 to 1974 greatly disturbed thriving Black communities like Mulvaney Street across the U.S. The initiative sought to modernize cities and eliminate what the governments considered blight, but the term applied less frequently to abandoned buildings and usually resulted in the intentional destruction of Black neighborhoods.

In Knoxville, the project of urban renewal displaced many Black families, churches, and businesses. Specifically, the entire Black business district around East Vine Street was eliminated. Today, The Beck Cultural Exchange Center, a museum in Knoxville preserving the city's Black history, estimates that about 2,500 structures, including at least 107 businesses, were destroyed alongside community institutions like the Carnegie Library, built for Black residents in 1917, and the YMCA established by Cal Johnson, a former slave who became a wealthy businessman.

The Beck strives to contest this erasure with over 50,000 objects in its care, including the Delaney family's last remaining home, which Beauford's brother purchased in 1935.

In 2018, the Beck began renovating the home to preserve this historic site in spite of continuing gentrification. The goal is to create the Delaney Museum and bring Delaney's legacy full circle in order to inspire young creatives in East Knoxville and art lovers worldwide.

People often regard the American South as a place that must be abandoned by artists for them to thrive professionally. "Unfortunately, so many of our talented young people feel limited in their growth and excluded from their field in the South, they can't rest themselves in a space that feels judgmental or burdensome," said Beck Center president, Reverend Reneé Kesler.

Preserving the Delaney family home revises that narrative. Once complete, part of the Delaney Museum restoration will include an artist residency: "We hope to bring in extraordinary BIPOC artists to study and share their gift with the community with an emphasis on how Beauford has impacted it," Kesler said. Black artists might leave the South for their careers, but they take the South with them wherever they go.

After all, Tennessee was where Delaney sketched on Sunday school cards and molded figures out of clay found in the churchyard while his father preached; where he began receiving his initial artistic training in 1916 from notable Knoxville artist Lloyd Branson. It's significant that the Knoxville Museum of Art keeps the largest collection of Delaney works in the world close to home.

"I think that for years, there have been people in the art world far beyond Knoxville who knew how priceless and valuable this art was and made that the center of the interest surrounding him," said Reverend Kesler, describing the importance of preserving the family home and extending Beauford's impact.

"With his art value increasing and being appreciated broadly, it becomes detached from the origin it was created in, and I think there begins to be less interest in the man himself. So for us at the Beck, it's always about the family, the history, and the foundation of the Black experience."

. . .

Perhaps his virtuosity as an artist and his intimacy as a friend is why interest in his work continues to mount. After successfully marking his gravesite, Wells is now raising money to create a documentary about the artist. Exhibitions centering Delaney, and acquisitions of his work, roll on.

A solo exhibition of Delaney's abstract works was presented in the Spotlight section at Frieze Masters 2021 and Michael Rosenfeld Gallery—which has worked closely with the artist's estate in recent decades and serves as Special Advisor and Representative of the Estate of Delaney—opened "Be Your Wonderful Self: The Portraits of Beauford Delaney" in September 2021; the latter was given rave reviews by Roberta Smith, co-chief art critic of The New York Times:

Each painting feels fresh and experimental—a risky lack of predictability that is shared by very few of his contemporaries. In this show, Delaney's abstract techniques first register in his figurative efforts in a 1962 self-portrait, in which the background, as well as the artist's face, sweater, and French beret, are pulverized in different color combinations. Each area could be expanded into an abstract painting.

The show is on view now at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans until July 17 and "explores the preeminent status portraiture held in the artist's life and work, following the trajectory of his career from what's known as his "Greene Street" period in New York through his ardent embrace of pure abstraction after his relocation to Paris." The way Delaney embodied his portrait subjects on canvas urged them to be themselves, a sentiment that is evidenced by the robust relationships he cultivated throughout his life, in every city he lived.

Delaney experienced care through the patrons that supported him, the friends that held his hand through mental illness, and those individuals who took it upon themselves long after he had passed to honor him as an individual with no reward or obligation steering them. Far beyond the vacuum of big cities, landmark institutions, and white walls, Black artists deserve this kind of lasting attention and care.

And truth be told, we all want a love like Delaney had—a beloved community that invests in our well-being because we are valued way more than any painting ever could be.

-

Notes:

- Link to the original page on Scalawag: https://scalawagmagazine.org/2022/06/beauford-delaney/

- More by Tyra A. Seals

-

6.29.22 via Scalawag

Tyra A. Seals is a writer and historian of African diaspora art. Her research explores the sites of origin that have transformed Black women's artistic practices over generations and the realities that affect their ability to move and create freely. Tyra has written for and worked alongside various entities including Art Papers, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, and Michael Rosenfeld Gallery. Tyra is a proud Atlanta native and alumna of Spelman College, where she studied English and Art History and graduated cum laude in 2018.

Portrait of American artist Beauford Delaney (1901–1979) by Carl Van Vechten. Wikimedia Commons.

Tombstone of Beauford Delaney, installed at the Parisian Cemetery of Thiais during the summer of 2010.

Baldwin sitting at his work table in his home in the South of France, 1972. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of The Baldwin Family