PHOTO: Ruckus

︎ Huff Gallery, Louisville

Personal is Still Political

The Women’s March on January 21, 2017 served as a rallying cry for women, marginalized groups, and their allies across the United States. Faced with the prospect of Donald Trump’s presidency, American feminists took to the streets of Washington, DC in a show of solidarity against the misogyny Trump represents. The effects of the march have echoed through American culture for the past year and are now finding their way into museums and galleries. Even within Louisville’s somewhat insular art community, one can observe a surge in feminist art and narratives of resistance.

Personal is Still Political is a collaborative exhibition by artists Lisa Simon and Skylar Smith who, like so many others, were inspired and uplifted by the Women’s March. Before encountering work from either artist, viewers are first presented with a low pedestal littered with pamphlets and brochures supporting causes like Planned Parenthood, the Center for Women and Families, and the Fairness Campaign. The tone is set: Simon and Smith have created an exhibition that is both politically charged and pedagogical. The inclusion of pamphlets and other information challenges viewers not only to consider the ideologies presented in the artwork, but also to take an active role in political change.

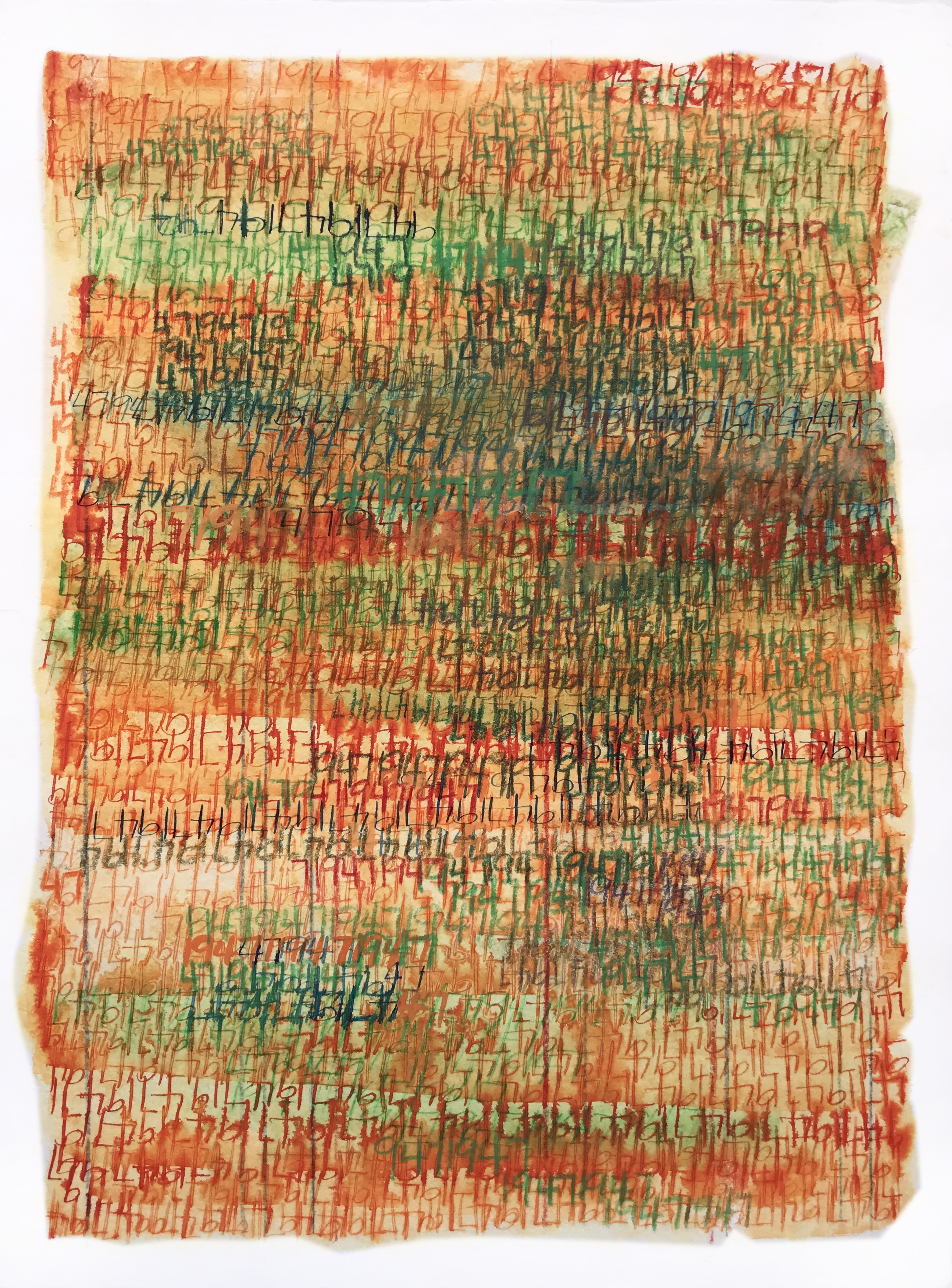

Past the informational table, Skylar Smith’s monumental painted banners fill the gallery and confront the viewer with an array of color. Women in pussy hats marching on Washington, silhouettes of early suffragists, and images of protest from around the world float and overlap in shades of yellow, orange, blue, and magenta. On the wall to the right are images from Smith’s “Suffrage” series, which include dates written over and over again, signaling the years that women and marginalized groups gained the right to vote in different countries. Smith treats the composition like an abstract painting, shifting the colors to create indistinguishable forms within the pattern of repeating numbers.

Complementing the figurative and abstract work of Smith, Lisa Simon’s collages and assemblages bridge 20th-century imagery and contemporary feminist issues. Exclamations issue from the mouths of cartoon cutouts intermingled with ads from the 1950s and 60s. The images are nostalgic but the text is jarring: “Romance dies at the touch of dishpan hands” and “She’s seen more ceilings than Michelangelo.” The work challenges the notion that such blatant misogyny, not unlike words we have heard from our current president, is acceptable in this day and age. Simon draws parallels between the camp of 20th century advertising and the absurdity of the current American political landscape and questions why, after so many waves of feminism, we are still hearing women degraded in the same ways.

Simon and Smith created this exhibition out of a need to speak out against oppression and also recognize the feats women have accomplished despite subjugation. In their statements, both artists admit to working outside of the techniques and practices with which they are comfortable. Simon states that the work is “not personally satisfying, and actually irksome and exasperating.” The discomfort is palpable—there is political angst present in the work but there is also a sense of reticence. Instead of channeling anger at their frustrations, Simon and Smith both seem to be searching for positivity and encouragement from their feminist heroes.

Skylar Smith’s “Suffrage” series began during the presidential primaries of 2016, as she first considered the possibility of a female president of the United States. She began to explore the history of women’s participation in American politics and found voting rights to be “intrinsically linked to hegemony and oppression.” By noting that women of color were prevented from voting long after white women, Smith comes close to addressing the intersection of race and gender discrimination. While she draws parallels between marches for women’s suffrage across the world in the “Marching” series, the work fails to discuss how some of these movements operated in direct contradiction to each other.

White suffragists of the 19th century such as Anna Howard Shaw actively fought against voting rights for Black Americans, fearing that Black suffrage would impede women’s progress. Should Shaw and her contemporaries be equated to the women of color who helped orchestrate the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, such as Anna Hedgemen, or trailblazers like Sojourner Truth? Truth famously called attention to the intersection of racism and sexism in her “Ain’t I A Woman” speech as early as 1851. It is troubling that “Shaw” appears right next to “Truth” in Lisa Simon’s installation, Naming Stars.* Simon covered the central pillar of the Huff Gallery with white, unglazed porcelain stars, each stamped with the name of a feminist icon. Simon places all of the names on an equal plane with no context despite the conflicting aspects of these women’s histories. Ultimately, the past failings of white feminists need to be addressed amidst the ongoing struggle for intersectionality within contemporary feminist movements.

The way in which intersections of race and gender are not confronted in Personal is Still Political represents a larger problem: white feminists have historically been silent in regard to the multifaceted oppression women of color face. As white second-wave feminists fought for reproductive rights in the 20th century, they tended to ignore the unique ways women of color had been denied power over their own bodies, such as forced sterilizations. We also cannot forget that in the 2016 presidential election, 53% of participating white women voted for Donald Trump. Gloria Steinem, a respected and outspoken feminist since the 1960s, stated at the Massachusetts Women’s Conference late last year, “The problem, and what [many feminists today] are not saying is that women of color in general—and especially Black women—have always been more likely to be feminist than white women.” Steinem’s assertion reveals that white feminists, no matter how established they may be in their ideologies, still have the capacity and the need to learn from women of color.

Black feminists and women of color have been instrumental some of the most important resistance movements in the United States. As they continue to propel the feminist movement forward, it is crucial that we recognize and celebrate their role. I am certain that Simon and Smith both appreciate what women of color have done to advance feminism in the United States, but following a long history of silence, it cannot go without saying.

On the way out of the exhibition, one is again faced with the table of informational flyers and pamphlets—a reminder that the artwork on the walls is a call to action. Simon and Smith have opened up the conversation of political and social progress, a conversation in which there is always room for growth and rejuvenation, and they ask their viewers to participate as well. The underlying message of Personal is Still Political is that brave women have fought their way out from under the hand oppression before, that we will not let their work be undone, and that we can and will continue to fight for the rights of the disenfranchised.

*Since this review was published, artist Lisa Simon informed me that the name Shaw as it appears in Naming Stars refers to education reformer Pauline Agassiz Shaw, not Anna Howard Shaw.

-

Personal is Still Political is on display at Huff Gallery until March 31.

Huff Gallery is located at 853 Library Lane, Louisville, KY 40203 and open from 7:30a-10p Monday - Thursday, 7:30a-6:30p Friday, 8a-5p Saturday, and 1-8p Sunday.

Related Programming:

March 31 | 1-3p: Closing Reception

Notes:

- Skylar Smith

- Branigin, Anne. “These Are the Women of Color Who Fought Both Sexism and the Racism of White Feminists.” The Root, March 15, 2018.

Mary Clore,

Contributor to Ruckus

3.23.18

“Environmental Print Saturation” 2018, Mixed-media collage. Photo courtesy,

Lisa Simon.

“Environmental Print Saturation” 2018, Mixed-media collage. Photo courtesy,

Lisa Simon.

Photo courtesy, Ruckus.

“1947, India” 2017, ink and colored pencil on handmade paper

Photo courtesy, Skylar Smith.

Photo courtesy, Ruckus.