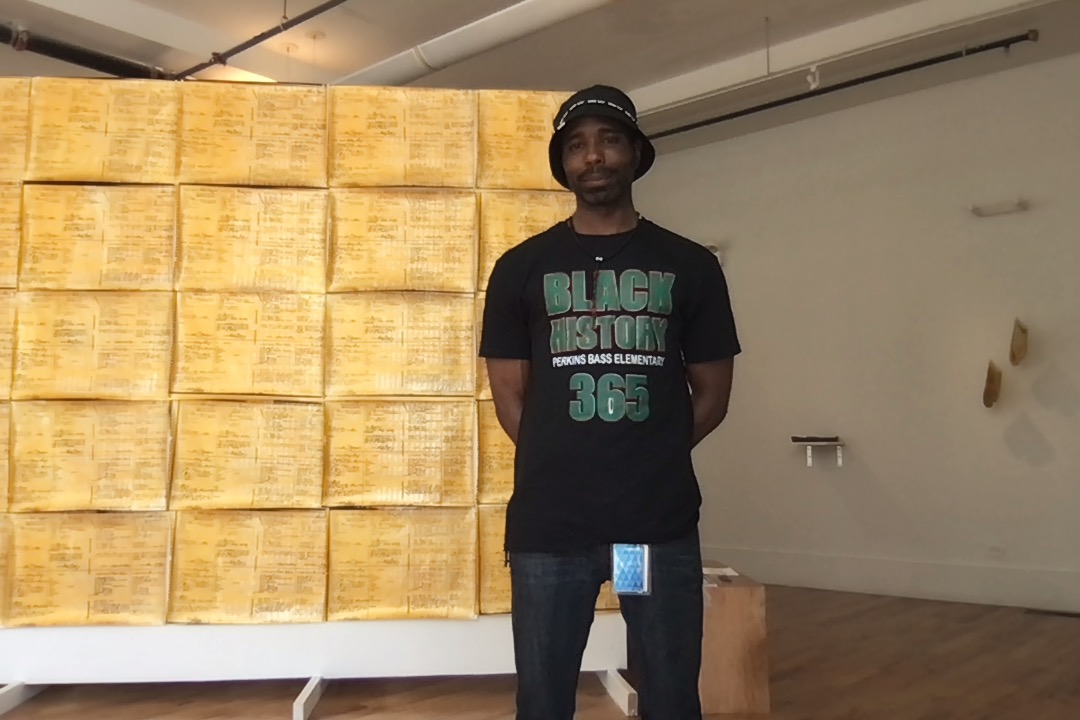

Above: Detail of WallPAPER of Respect: The Gold Freedmen (2022), Shonna Pryor, Acrylic Paint, Silkscreen on paper, 24x18” (30). All images credit of Robert Chase Heishman (RCH Studio).

Relic

Review

A star-spangled hoodie. An amorphous mass of shea butter. An undulated anal plug. Stonecast moldings of door knocker earrings. Pristine Black church fans. Gold silk screened ledger pages. These are a few of the artifacts carefully left behind by artists Abigail Lucien, Janelle Ayana Miller, Kevin Demery, Lakela Brown, Rhonda Wheatley, and Shonna Pryor in, Relic, a group show curated by Chicago-based Ciera Alyse McKissick and sheltered in place at Arts & Public Life (APL). Each relic holding its own memory and legacy with the remnants from each of the artists and their community lingering, remaining still. Etymologically, relic comes from "reliquus", which means remains or more specifically that which remains. The foregrounded distinction of “that which'' is important to note here. It attends to the recognition of survival—and not just a coincidental survival but a persistent survival that honors the vitality of its existence. It recognizes that some things didn't make it through the journey, some things were destroyed, and some things faded into oblivion, but that which remains, here, with us, in this space, on the corner of S Prairie Ave and E Garfield Blvd, means something. Whatever meaning attached to each object emergently presents itself to you over time in a quotidian nature. There is magic in our everyday and there is power in the tools of our everyday. Relic highlights this with the intentionality of preserving this shared moment not only through the objects in the space but through our beingness in the space. Makeshift photo booth to your left capturing playful group portraits and outfit checks, a mini keepsake library to your right with heavy hitters such as Picturing Us by Deborah Willis and Flash of the Spirit by Robert Farris Thompson to ground you while taking it all in, and finally you, center stage, witnessing this time capsule in real-time. Becoming a part of it in a way. Leaving your own memory and remnants—(re) configuring that which remains. Subtly, McKissick offers a site that positions you to tessellate with that which remains and how a spirited object can be a tool can be a vessel can be a carrier which is a relic.

Taking the show in, you gain a sense of the utility offered by each object and simultaneously each object reveals itself as a “spirited object”, an object intentionally preserved holding all of the possession left from every stage of its existence, a witness to a relationship. Consider, for example, the Afro pick: a tool created more than 5,000 years ago deriving from ancient Egypt, beginning as a functional tool and refiguring itself over time in direct position to the current cultural and political climate.1 Lakela Brown’s Still Life with Seven Gold Impressions, calls forth this history. A stone slab imprinted with door knocker earrings forming a Tetris-like cascade off of its axis reminds me of what you'd imagine the ten commandments were inscribed on but instead of words weaved together to form sentences, symbols in geometric shapes of varying sizes are embossed with gold overlay depicting a coded language of its own. The use of our local beauty supply store STAPLE makes me blush with adolescent admiration. There is a tender loving care taken with the earrings as you recognize every curvature and crease permanently marked into the stone—giving it life. Brown nods to the importance of preserving black cultural aesthetic practices as she delineates the significance of her existence in the piece, of our existence in history, and of the everlasting presence of black cultural aesthetics in the futures near and far.

We know “There Are Black People in the Future,” as Alisha Wormsley directly asserts in her 2017 billboard text highlighting the need for Black people to claim their physical and metaphysical place in every direction of time. This work interestingly grounds McKissick’s approach and curatorial vision with Relic. The reassurance of black presence in every direction of time isn't a new proclamation. We knew that there were Black people in the future through the direct actions of Harriet Tubman. We knew it through the exuberant declarations of vibrant singer, violinist, and dancer June Tyson and Sun Ra. We knew it through the memory vessels2 exquisitely crafted by family and friends to honor our folks in this realm and the next. We’ve always known. So, where Wormsley’s bold assertion seemed directed toward an ambivalent audience, McKissick intricately weaves the work of the six artists to communicate a small but significantly different message, and that message is we know that black people are in our futures and that these are the tool objects left for our communal survival. Entering the capsule (read: APL) you are almost struck down by the sheer magnitude of Shonna Pryor’s WallPAPER of Respect: The Gold Freedman. Moving in the same step as the revolutionary Chicago monument, the “Wall of Respect”3 WallPAPER of Respect: The Gold Freedman inserts itself as durable and undeniable. The replicated ledger papers used in Pryor’s work are from the archive of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, simply known as the Freedmen's Bureau. With the emphasis on paper within the title, Pryor highlights the perpetual flimsiness of “The American Dream” for Black people. But as the ledger papers repeat and layer and take up more and more space, you envelop into a recognition that for our ancestors, this piece of paper symbolized a departure point, a point of reshaping and transformation of our futures of black mobility. Translating the names written on the ledgers is nearly impossible but quickly you understand that your fixation on deciphering the words is removed from the point. Its lasting impression is in its vastness. In its simplistic, domestic overture you are invited to mine your own history and connection to the piece. You ponder over your connection to the land on which you stand, and ask, what are the implications lingering from the hands that tended to the land on the corner of S Prairie Ave and E Garfield Blvd? Are their folks receiving the reparations deserved? Where Pryor’s WallPAPER of Respect gives us a significant domestic entry point, in equal immensity, Janelle Ayana Miller offers us a large-scale installation of pentecostal breath.4 A muted cyan blue archway, reminiscent of a church’s stained glass window depicting a holy figure, lies a collection of another kind of holy figure. Vintage Black church fans are tiled together. Each fan breathes new life into you. One reads “A Happy Pair” and another reads “Thank you God“ and they all read joyful, joyful. These artifacts ground me in a complicated history of love for the Black church, and I am reminded of how much of my love practice is rooted there when viewing this work. I am drawn into the fans by all of the promising smiles, by the endearing eyes, but mostly by the collective flair and devotion imbued. I am suddenly taken through a time loop of the foot-stomping, hand-clapping, and fan bellowing revival I experienced as a child. These quintessential accessories and portable billboards are known for their abundance in Black church pews as early as the 1920s and, for this reason, there is a prevailing expectation that these artifacts should show signs of weathering due to their age and intended use. This is not the case. I hear an elder during Sunday evening service beginning her testimony with “I don’t look like what I’ve been through”. The fans echo this exact sentiment. With Building Virtue, A Study, Miller scaffolds excitement using the fan as a vehicle drawing purpose beyond utility with simple affirmations supported by cultural imagery. The archway is an entry point to reimagine a fantastical space where black people are unabashed, uninhibited and forever grateful.

Musician Camae Ayewa, better known as Moor Mother, recalls the efforting that black folks have done historically to preserve our history. “Enslaved folks, who had and owned almost nothing, managed to leave small time capsules that in some places have been found beneath their cabins.” Moor continues, “When we grasp bits of our ancestors’ lives, we benefit from the wisdom they worked out.”5 Beneath our ancestor's homes, this is where I imagine we would find Kevin Demery’s Shell, Rhonda Wheatley’s Ritual Arrangement for Opening Manifesting Portals, and Abigail Lucien’s A Softening. Demry’s angelically laid star-spangled hoodie acts as a literal vessel holding the remnants of its host. The outline of the figure held in this hoodie is less of a body and more of a fluid, ghostly figuration. The host seems to be disintegrating right before your eyes. Its position on the floor furthers your inquisition of “what happened here and why? Isn't anyone going to help?” But what help is there to offer? The figure is made of seashells adding more to its unearthly composition. It seems that there is no amount of saving that can take place for this figure now—only atonement. For many of us, the hoodie holds a strenuous tension between protection and pain,not of our own doing. However, the seashells operate as reverence to our ancestors who once decided to depart this plane by the sea while highlighting the transient relationship Black people have with water. Shell whispers “sea see me” so elegantly. Rhonda Wheatley’s Ritual Arrangement for Opening Manifesting Portals holds a similar ephemeral nature. Several clocks read 11:11 (make a wish!) antennas point in every direction receiving transfixed transmissions from near and far, and earth in the form of plants, stones, and crystals line the table, coming together line by line and intention by intention like a Betye Saar or David Hammons assemblage. Wheatley has re-foraged found objects and various organic materials supercharged with a magnetism that makes you feel comfortable enough to reach out and touch them. This portal is a rupture in the space. An intentional moment to harness your own power of manifestation and make a gentle demand of the universe. Wheatley’s altar pieces arranged together symbolize a moment of relief. Beyond the spirited objects, Wheatley offers us time, ritualized time, to honor, wish, and say our tender prayers. Where time is carved out to manifest with Ritual Arrangement for Opening Manifesting Portals, time is carved out as a slow unraveling in Abigail Lucien’s 16-minute and 32-second video, A Softening. Soft doesn't seem soft at all with Lucien. An undulated mass of shea butter is held like life depends on it. It’s cherished, anchoring, and shapeshifting. It’s not shea butter, it’s shea butta. And with the same alluring familiarity, you watch Lucien coat her body in an invisible layer of protection as the mass is held, hugged, and loved. Lucien molds her bare body to the shea butta where organic materials meet in a sculptural intervention. You are struck by the equally yoked ritual that you witness unfold over time. And while you are unable to touch or smell this specific everyday material, there is a visceral reaction to your proximity with it. You know that it's nourishing, rich, and coveted as an ephemeral treasure, but somehow its temporality feels intrinsically limitless. Lucien wraps her whole body around the misshapen mass. You feel it softening under her warm embrace and not surprised with how it maintains. For Lucien, shea butta is a far reaching natural resource, a relic, that softens into you and you into it simultaneously.

Upon my second visit to Relic, Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction came to me almost as a spark to a flame. Do you know this theory? It’s quite interesting. Le Guin’s The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction posits that the first human tools were not weapons but were containers or baskets to gather and bring home food and other resources. Focusing less on the knife, the ax, or blunt object of aggression as the first human devices and more on the carrier, the holder, and the receptacle as tools of communal survival. This sounds familiar, right? You can imagine it here, in this space, right? Church fan as a carrier. Hoodie as a carrier. Shea butter as a carrier. Paper as a carrier. Clock as a carrier. Door knocker earrings as a carrier. Butt plug as a carrier. Kitchen mittens as a carrier. Florida Water as a carrier. You as a carrier. Me as a carrier.

I asked each artist for an offering to this piece. It didn't feel right to only have my words here with you. I wanted you to know how they felt about their proximity to Le Guin’s The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction and if it at all made sense to them. I wondered what they imagined the function of their relic to be as the first human “tools” in a post-apocalyptic world speedily becoming our lived reality now. Here you have Shonna Pryor, Rhonda Wheatley, Kevin Demery, Janelle Ayana Miller and Ciera Alyse McKissick.

-

Citations:

- “The afro comb: not just an accessory but a cultural icon” The Guardian, Sun 7 Jul 2013

- A memory vessel is an African American folk art form that memorializes the dead. It is a general term for a vessel whose surface is adorned with an assortment of keepsakes and memorabilia from the deceased life. These vessels were often used to commemorate the dead instead of expensive headstones. This practice has roots mostly recently in the Appalachian South which derives influence from the Bakongo culture of Central Africa.

- The Wall of Respect was a revolutionary mural created by fourteen members of the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) on the South Side of Chicago in 1967. The Wall of Respect: Public Art and Black Liberation in 1960s Chicago by Romi Crawford, Abdul Alkalimat, Rebecca Zorach, is the first in-depth, illustrated history of a lost Chicago monument.

- Blackpentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibility by Ashon T. Crawley

- “Black History Month Has Ended. Here's What Experts Think the Black Future Will Look Like”, TIME Magazine, 1 Mar 2022

-

5.22.22

isra rene (they/them) believes in you and in me. isra believes in weaved webs of dreams tufted by our inherent connections of love, vulnerability, and care. isra believes in deep research. isra believes in writing love notes. isra believes in reading as meditation and the space between words as a playground. isra believes in the power of studying and the power of not knowing. isra believes in invitation. isra believes.

Install of Relic. On Left: WallPAPER of Respect: The Gold Freedmen (2022), Shonna Pryor, Acrylic Paint, Silkscreen on paper, 24x18” (30). On Right: Building Virtue, A Study (2017-present), Janelle Ayana Miller, Archival Church Fans.

Building Virtue, A Study (2017-present), Janelle Ayana Miller, Archival Church Fans.

Care Package for an Afro-Migration to Mars: Left Turn, Past 2 Moons, You Will Know (2021), Shonna Pryor, Aluminum Foil, Acrylic Paint, Reclaimed Items Vacuum Sealed on Wood Panel, 18x20”.

Shell (2020), Kevin Demery, Sea shells and one cotton hoodie.

Ritual Arrangement for Opening Manifesting Portals (2022), Rhonda Wheatley, Vintage clocks, clock radios, crystals, handmade sculpture, tarot cards, preserved plants and moss, vintage apothecary and perfume bottles, palo santo, other organic materials Installation.

When Boys Are Birds And Men Are Soil (2020), Kevin Demery, Drum Head with Projection.

On Left: Still Life with Seven Gold Impressions (2021), LaKela Brown, Plaster, Acrylic, 20x16”. On Right: Still Life with Eight Gold Impressions (2021) LaKela Brown, Plaster, Acrylic, 20x16”.

Images from the photobooth at Arts + Public Life. ID: Various pictures of different gallery visitors, who are walking by, smiling and posing together in front of a stationary camera.