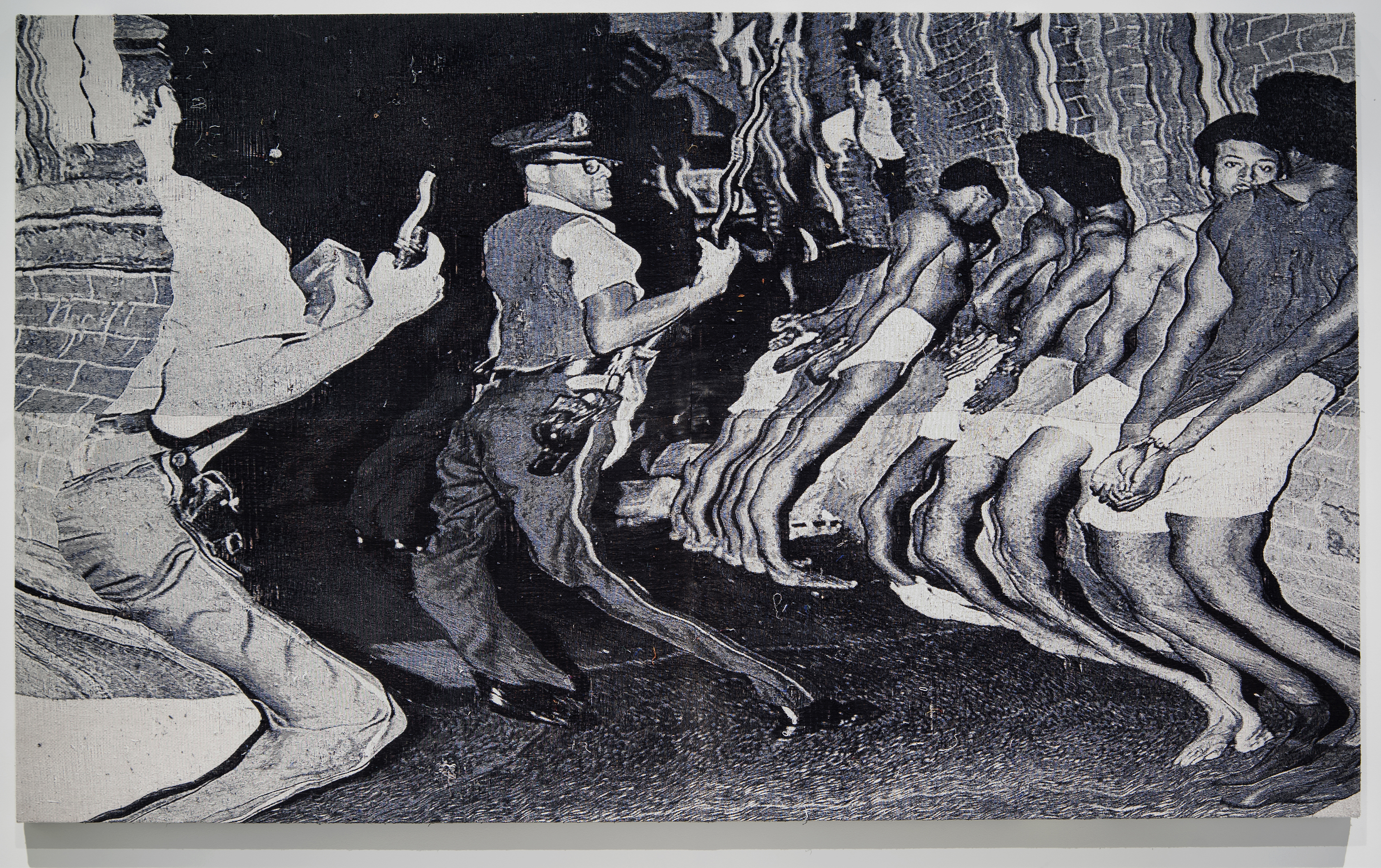

Above: Die Leitung, Distressed stretched Jacquard tapestry, 13' x 9', 2016-2019.

SPEAKING: Noel W Anderson

Q&A

with L Autumn Gnadinger

Noel W Anderson (he/him) is the current Area Head of Printmaking at NYU Steinhardt in New York City. Noel makes powerful, prescient work that manipulates imagery from what he broadly calls “screen culture,” in very literal, haptic ways. With Ahmad Jamal playing in the background, I spoke with Noel about his studio practice, his experience growing up in Louisville, KY, and his many fascinations ranging from French tapestries, to mathematics, to jazz.

L Autumn Gnadinger: How would you characterize your experience growing up in Louisville?

Noel W Anderson: Well, I'm the youngest of six. I grew up in the East End of town in the suburbs, to an amazing nuclear family. My father was a civil engineer. My mother was a social worker and a teacher. And when you grow up with that kind of academic space, that kind of intellectual space, rigor was always at the dinner table. There was never a day in my house when I was growing up where you were not required to think critically—which seems to be in my studio today. There's always been this consistent need to question everything, or at least produce questions; produce a curiosity to find answers.

LAG: And for you that is an outgrowth of the way you were raised in your family?

NWA: I think so, because now that I think about it, having gone to Ballard High School and getting into art there and learning that I didn't have to play sports to get into school: that really helped stimulate something in me. So, in terms of the groundwork for what the studio is doing now, I can definitely say that without Louisville, Kentucky, my home born and raised, (I rep Louisville to the end, 5-0-2), I wouldn't be here, you know.

But that brings me to another topic: if Louisville is such a significant space, why do people leave? Well, you leave because you need to find other perspectives, right? Louisville has a bunch of perspectives, but there are other perspectives. There are other vantage points with which to see the world and to initiate meaning—that could align more with the person who you are becoming versus the person who you think you be, you know? “What else is there?” It's the other side of the binary. It's the third term, if we will. Actually, that’s the point. It allowed me to find value in things art-wise, that a lot of people may not initially find value in.

LAG: Does anything stand out as an example of something that you saw value in that others couldn’t see?

NWA: So I tell this story all the time, right? People say, “how did you get started on tapestries?” I started going to the Met. I would go to the Met all the time because the Met—I'm going to say this until the day I die—is the most untapped resource for artists in the world. I've never seen anything like it. Or the Louvre, you know, just major museums. There are millions of years of ideas in there. So I wanted to go find those ideas. And then I remember my old art dealer and friend Jack would say, “you got to go to the Met on Friday nights.” On Friday nights nobody would go except for artists.

And you used to be able to go and famous artists would be there. Like, Richard Tuttle might be there looking at a rock or something. I'm speaking somewhat metaphorically, but forreal, he would be there looking at a rock. And I would go in and say, “well, what’s Richard Tuttle looking at? Let me stare at Richard Tuttle.” And then I'd be like, “what the fuck am I staring at him for?” Tuttle had already figured that rock out. I needed to find my rock, which took me to a room that nobody was in: the tapestry room. And I was just like, “there's something marginalized by this space, because nobody's here. Everybody's up in the 18th century wing.” So that's how it started.

LAG: All of that tracks with what I see in your work: this intense curiosity and interest about history. What else do you find compelling about Renaissance tapestries? And then how does that inform the way you think about your own work or your own tapestries?

NWA: On a very formal level, I was taught the modernist and the postmodernist move where you take the medium to another territory. And when I was doing research on how these French weavings that I'm really into were made, I thought to myself, “Oh, they really have something here.” Because that weaving, starts with a painting. The artist has to make a painting first—a cartoon—and then give it to the weavers. As soon as that happens, an artist like Peter Paul Rubens might say, “I'm not making enough money,”—and this is real talk—he'll say, “well, then I'm going to give the cartoon to the printer.” Now the printer can make 50 of them and we can make money that way. So, right there, the image has gone through three iterations and that means, formerly, those processes are related.

It started with that kind of formal curiosity. And once I started reading more, I started getting into use of mythology, the imagery, the way, the politics and aesthetics of weaving, and how that gets entangled with the discourses of colonialist theory. You know, King Leopold II was terrible—he cut off people's hands—but what kind of art did he have in his house? What kind of spatial, interior design allowed him to psychologically produce the shit that he produced?

And I find it in the marginalized stuff. What kind of chair did he sit in? What kind of tapestry did he have on his wall? So that's how I got there. I was like, “what are the quiet players? What is the rhythm section?” I like to talk about jazz because that's how the rhythm section works. The piano and the drum and the bass, they're the fucking thing that drives the sound system—without Thelonious Monk organizing space, what do you have? So like, What is the rhythm section that produces a Leopold? What is the rhythm section that produces a fucking Jefferson? The things that they lived with. So that's where it started. I wanted to find power’s rhythm section.

LAG: And then you took that rhythm section, so to speak, and this kind of formal language that you discovered there and began translating this over time into the tapestry work that people know you for now, these undulating—altered—images that we might recognize from history. How would you talk about the way that rhythm section, or those quieter players, are now showing up in your work?

NWA: Cool. Like any good jazz ensemble, they all get to speak. So they're starting to speak in the form of Jacquard tapestries, in the structure of weaving. And that structure is specifically entangled with the origin of digital technology. So we have someone like Joseph Marie Jacquard, who had this very simple way of developing an image through punch card registration. You have a card that you put into the weaving machine and has a bunch of holes: wherever there is a hole, thread goes through. Wherever there is no hole, thread does not go through. It's fucking binary code, period. You're either on or off.

Anyway the Englishman Charles Babbage picks the thing up later and creates what we now know as the grandfather of the computer. Every time you're looking at a screen, every time you're dealing with something that's quasi—if not fully—binary, you're dealing with a textile. That even goes down to identity politics. And that is what we’re doing, right? I'm finding images that correlate to screen culture and then reintroducing them within the discourse of hegemonic structure. I'm reinscribing these images of either resistance and/or oppression back within the rhythm section, or within the objects that define the rhythm section of power.

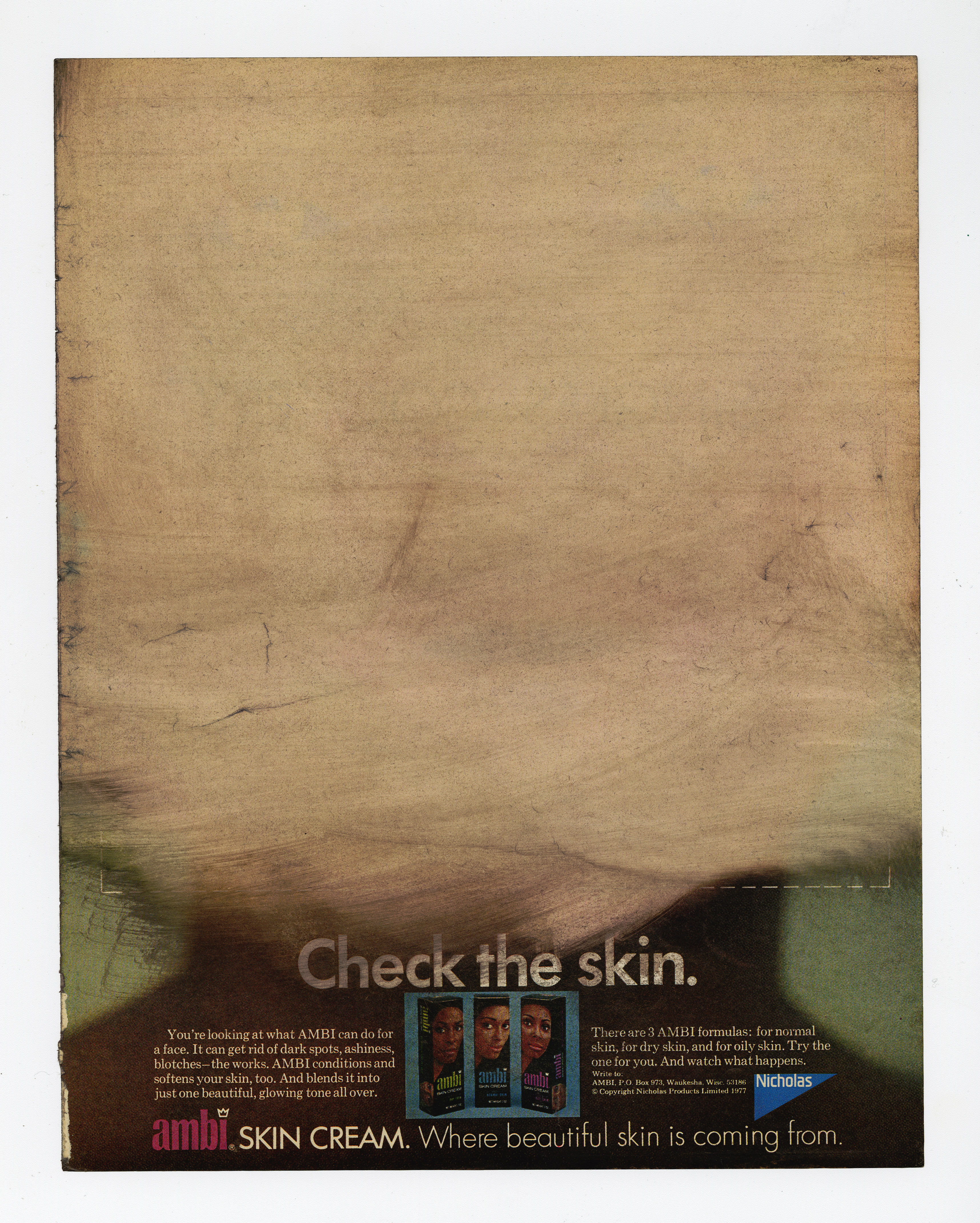

LAG: Your ideas about screen culture feel related to how I've heard you talk about your hoarding of Ebony magazines in the past, and how that represented an archive for you. Specifically, then editing that archive—it feels related. How are those actions similar or different for you?

NWA: It is, because if we go to the ontological ground of screen culture, what we're really talking about is lenses. You're talking about lenses, gazes, perception, and screen culture is a material manifestation of those internal processes that engage the real world. And I think that conversation of experience in “the real” comes into play with how I attack the tapestry. When I have them made—I work with weavers here in the States and in France—I work on the image, both analog and digitally, and then I send it to my weavers and they figure out how to weave it. And when it comes back to the studio, I don't just rest there and stretch it and move it on. I tack it to the wall and I—literally with a nail and my hands—I pull out threads, thus trying to destabilize the image.

If I think about how it relates to the Ebony works: those are pages torn from Ebony magazines that are then either erased by hand or being manipulated with chemicals, so that the literalness of the image—the construction of the image, which is really just ink on paper—challenges the accuracy of the representation. So the same thing happens with the tapestry: the thread itself is nothing but a bunch of dots of ink. And when I'm picking the thread and trying to move it out of my way I am, in a sense, challenging the accuracy of these images and the representations that we give ourselves.

LAG: Another thing that's coming to mind is your work, STOOR, which plays sections of the series Roots backwards. You're taking the temporal nature of video and like throwing that on its head.

NWA: What STOOR offers in a reversal of time—when you break time or you break anything—is like Heidegger's hammer: you have to identify “what was it doing that I needed it to do anyways?” When you break time you have to figure out what's happening, and “Why is this?” And it forced me to really recognize how the characters were relating to each other. So now Louis Gossett Jr., who plays the character Fiddler, becomes Kunta Kinte’s surrogate father on the plantation. I was able to watch him care for another Black man. In the reversal of time, you start to notice that there might not be a distinction between breathing forward and backwards. And you can't tell whether or Fiddler is feeding him water or taking water away. There's a particular kind of indecipherability about what's happening. Things get stripped down to only that he is caring for someone. That's it. It just strips everything down to a very basic, ontological, level: he just cared for someone.

Then you watch the dance of him getting flipped into the air with the rope. He's getting jettisoned back into a violent space. Then there's a whole other thing I realized when I was making, I was like, “Oh, this is just birth.” There's a violent act occurring. He's passing through a threshold. He's going back into another place and he's being reborn. There's a specific kind of violence that I—unfortunately, as a person of color—ascribe to the development of Blackness. I'm making these new tapestries called, Initiations. Large-scale tapestries. And they're all images from art, my archive and other archives—growing archives—of police brutality. And those images are being woven into tapestries. And for me, they're all called “initiations” because you go through some kind of violent act: you're born into it. There's a flagellation—there's a religiosity of that beating. There's some kind of humiliation—kind of like a frat thing that's going on. There's a violence that Black masculinity seems to have to go through to be initiated or realized or interpolated into a certain kind of subject. You know what I'm saying? And that is forever in the work. This realization of Black subjectivity through imagined rituals. And those rituals are not limited to Black communities. They're not limited to that. You get ritualized outside yourself too.

It's been my experience, that becoming Black, seems to get filtered through an outside force that was informed by some other being in the world that creates a kind of violent act. It seems to me that my Blackness has always been initiated through some kind of violence. Not always, but in some regard, there's always been some kind of violation. I'm always snapped back into it, a recognition that it's there, you know.

Inside my family home, it was like, “yeah, you Black, whatever, what are we talking about?” You know, “get up, fix the TV”, you know, “fix the rabbit ears. Why are we talking about what we already know?” When I was like six years old at the dinner table, my family had a small TV in the corner with rabbit ear antenna. The image would move and stabilize, and then warp and wobble and evade capture. And my father would say, “Boy, go fix that.” And as a man who went to MIT in the fifties, when he broke code, you didn't play. So I would run over to that corner and I would fix it. And I would try to stabilize the image by messing with the rabbit ears. And while I recognized that that image on the screen wasn't real, in the sense that I could stabilize it and destabilize the electric field of my body—everything I was learning at that table was more real than anything.

I think I mentioned it in a little piece that I wrote for my first solo show, Black Origin Moment, that our table was a military force. That table was a tactical territory. That was where, over peas and corn I learned my P's and Q's. I learned when to speak and when not to speak. I learned how to be Black. I learned value and self. General fucking Schwarzkopf, General Patton, or Colin Powell, couldn't have developed a better tactical force than the mother fuckers I had at that table. I had my mother, my father, my grandmother, my Nana—you know, the way she doted over us, but was quick to put your back in line, if you played.

And that's interesting, ‘cause I didn't even get there—that kind of realization until I realized that there are other players like when we were talking in the beginning. There are other players—other instruments in the rhythm section—that I didn't even realize had function. That dinner table was the ultimate percussion. On one side my mother might have been playing Aretha, and on the other side my father would have been playing Monk. And I was in the middle I was experiencing a polyphonic polyrhythmic percussive performance of Black perfection.

Now that doesn't mean that every day the rhythm section was playing proper ‘cause sometimes you'll be at that dinner table like, “I don't like what y'all planning out on this stage. These brussels sprouts? No not here for this rhythm tonight.” But most nights at that dinner table, I enjoyed the music that was being played. Or at least it helped me, you know?

LAG: As somebody who's at the top of his field, do you have any advice for either your younger self back in Louisville or other people who are from the Midwest or mid South, our region, who might be entering into some kind of national conversation about art?

NWA: I gotta tell everybody: your voice matters. Your voice has value. Specifically in the post civil rights world that I grew up in, there was always this sense that Southern voices were not as intellectually inclined—real simple like. And I actually liked that position because it puts you in a subject position of invisibility, and the person who's most invisible is probably the one who has the most power. But anyway, your voice has value.

Also I was lucky enough to have a teacher at Ballard, Dennis Whitehouse, an amazing man. And he instilled in me—along with my father and mother as well—a recognition of the value of the fundamentals. I feel like a lot of people, if you don't live in New York or something, you see what's happening in Artforum, and are like “I just need to make those things!” And I'm like, “yeah, that's cool. Some of those things are kinda nice.” But a lot of them ain't that interesting. And I can't even fall back on the technical cause the technical is shit. So I tell students “if you can draw well, you're going to be just fine.” They're like, “Why is that?” “Cause you'll never run out of a pencil and paper, fam!” All that other technical stuff gonna fail, you know? So the fundamentals are key for me ‘cause I can draw my ass off.

I also like to tell people not to get caught up in the fads. You can get caught up in a fad and you can be making that stuff like everybody else, but what distinguishes you? That the trend becomes a trend and you just become another note in the trend. What the fuck is the point of that? You know, have questions and figure some new shit out. And be okay if the new shit doesn't work all the time. ‘Cause the new shit don't work for nothing. Right? I've been on this particular journey for 10 years, and I'm just now figuring it out. And I'm really quite happy, to be honest, that people didn't know about me before, when I was coming out 10 years ago. I made a lot of bad, bad things—a lot of shitty art. We have to make bad art, you know?

LAG: Is there anything in this conversation that you felt has been missing, that you would like our readers to either know about you or just be thinking about generally?

NWA: Yeah, I was thinking about how one of the main contributors to my artistic pursuits in terms of Louisville was the Speed. That's why I really want to do a show at the Speed one day, because I had these trips I used to do. It was very secret. When I was in high school and I finally got my license, I had this 1986 Jeep Cherokee. A goddamn piece of shit—It was beautiful.

LAG: Hell yeah. I would kill for one of those.

NWA: Fucking awesome, right? It was bronze and rusted. My father and mother bought it for me. I loved that thing. It had a big ass hole in the floorboard over the back-left seat that you could smell gasoline through it. It had one good speaker: on the passenger side of the front of the car. When anyone sat there, I had to tell them, “move your legs,” so we could all hear the music. I used to get in that car to take the secret journey down to the Speed. Nobody fucking knew I would go to the Speed.

I would park across the street at what was like, frat row. And I would walk across the street and I would go into the Speed for free. And I would walk upstairs and I would stare at all those Renaissance paintings for hours. Oh my god. I remember that. I would stare at those fucking paintings for hours. They had this fucking Rembrandt up there—goddamn, the Dutch! They had one of the ones where she had the white collar around the neck. I was like, “Goddamn this thing glows!” I never saw anything like it. I would probably go once a week for a few years.

And then when I came back during college I would go down there periodically and I would just stay in that room. That place was a godsend. That was my time. And now realizing it, you know, getting older and, and learning how to articulate those ideas on a very intimate level. I didn't know what that force was, but that force and I were intimate. Sometimes that force would call me like, “no, no, no, check out this Saint Jerome! Look at the way the forehead is painted!” And I would just stare at that forehead for hours.

That force and I are intimate when we go to the Met too, and that is what got me to the tapestry. That force has always been with me. I don't know what to call it, but a force. That's what Louisville did for me—that's what the Speed did for me. Y'all they should let me curate a show with the collection there. Sorry

LAG: I'm not being overblown to say that the Speed would be so lucky to have to have you coordinate with them on anything: a solo show, you curating show, or both. It'd be incredible.

NWA: Thank you. You know, we’d have a fucking blast. The Speed was a safe haven for me—all those feelings of curiosity in that time at the Speed were so clearly resurrected when I went to the Met. Those two moments I think were portals—seismic shifts in my very becoming

-

Notes:

-

12.29.20

L (they/them) is an artist, writer, and current MFA candidate at Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia, PA. They are originally from Louisville, and an editor for Ruckus.

Noel W Anderson

Wink, Altered Ebony magazine page, 13" x 10", 2010-2019.

he's Mean!, Altered Ebony magazine page, 13" x 10”, 2010-2019.

Check the Skin, Altered Ebony magazine page, 13" x 10”, 2010-2019.

Hands-Up, Stretched Jacquard tapestries (4 count), 44" x 42”, 2016-2019, Collection of Hunter Museum of American Art.

Die Leitung (detail)

.