ABOVE: Paul Michael Brown at home with his cat, Mimosa.

︎ Paul Michael Brown, Lexington

SPEAKING: Paul Michael Brown

Q&A

with L Autumn Gnadinger

Paul Michael Brown is a writer, researcher, and curator, whose work puts a “focus on queer and self-taught practitioners from the South.” Brown was recently awarded a prestigious Arts Writers Grant from the Andy Warhol Foundation. At the time of this interview, he is transitioning away from his directorial role at Institute 193 in Lexington and into writing full time. The following conversation with L Autumn Gnadinger is an outgrowth and reflection of this professional transition, as well as the work that Brown has done over the last several years.

L Autumn Gnadinger: I know you have been involved with Institute 193 for many years now, but you've been specifically working as the director of its Lexington gallery location since 2017. How did you arrive at that position?

Paul Michael Brown: I moved to New York after leaving school and started doing some freelance writing and interning at galleries all around New York City. Eventually I got in touch with Phillip March Jones, the founder of 193, who had since moved to New York to run a gallery and ended up writing about some artists from Lexington that he was showing in New York. That was my introduction. But at the end of two and a half years, I was not doing any work in the art world that was actually paying me. I was working for free a lot, and then making money by driving trucks, for the most part. So I was kind of ready to move back and actually do something that I cared about.

LG: When you said you were driving trucks, what did that look like? What kind of trucks?

PB: Like big box trucks. I was working as a production assistant for a marketing company, and they built these really bizarre events that were basically product launches geared towards magazine editors. For example, we had a contract with Olay. Every season when they would put out a new line of products, they would build these elaborate silly events that were only open for about 36 hours. Then, editors from Vogue, Vanity Fair, or Elle would all come through and look at the new products and see if they wanted to include it in their summer picks. These companies would spend $150,000-200,000 to try and entertain 30 people.

Most of these were in New York, but we also had some traveling contracts. I actually did a promotional tour for Olympic, which is a deck stain brand. And so I went for a tour of 27 Lowe's parking lots in the Midwest and Midsouth for six weeks.

LG: That sounds like an interesting backdrop to be in while moving back to Lexington and thinking about the relationship between New York and some of these Midwestern or Southern places. What was on your mind at that time? Or, for you, what was the relationship between New York and these spaces – these parking lots?

PB: By the end, I was pretty burnt out on the commercial art world, even without having too much experience in it. I would still say that the gallery I worked for was an exceptionally good and fair space to their artists, but I'm not really cut out to be on the sales end of things. I also think I was sometimes bothered by how New York-centric the art world was. So it made sense for me to move into a job that was explicitly about finding value in art that is not taking place in New York city – not completely concerned with that world.

LG: One of the things that I think is really interesting about what Institute 193 does is a fairly consistent effort to publish books, in addition to the exhibition programing. What is the relationship between the project space/gallery and this collection of printed material?

PB: From the outset, the publications have always been something that we have found to be an important part of the mission to preserve and document the cultural landscape of the American South. The exhibitions are a good way to showcase that, but they're not always super useful in terms of making it more permanent in a historical sense. It's more geared towards building the scholarship and knowledge of the region. The publications that we've done are frequently the first such thing on that artist. The Stephen Varble one, for example, that's the first printed piece that's ever been published about his work. He was an early and influential Lower East Side performance artist who disappeared from history.

He was important to us because we had a show that ran parallel to a much larger exhibition at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in New York City. There wasn't a catalog produced with that show, but we wanted some sort of permanent record tied to the artist's work. The interesting thing about that book too, is that the collection it showcases was was gifted to a queer-focused archive in Lexington. So all of the contents of that book now live in Kentucky permanently, and we have the only published record of that artist so far.

LG: There is a lot of discourse and engagement with the idea of archives in contemporary art. That's been going on for 10 years or more, and I would still say it is relevant in 2020. What I find really striking about your interest and work on archives is that it seems to be so grounded and literal compared to most of what is out there: a lot of interesting, but abstracted musing. You’re very focused on either exploring existing archives or creating archives where nothing existed before, especially in the context of this Southern and hidden queer-history landscape. How would you begin to talk about your relationship to the idea of archives or the archival?

PB: That’s true. Though, I also appreciate esoteric understandings of what an archive can be. There are a lot of queer theorists that have covered the idea of queer archives and what it means for something to be a queer archive, but I think the interesting thing about being based in the South and doing work within the South is that, a lot of the time, there isn't quite the luxury of having a physical, capital “A” archive to play off of or work from. So I have been trying to work with, and talk about, the kinds of places where those efforts are being made.

The Faulkner Morgan Archive in Lexington, for example, is a pretty remarkable place. It’s probably one of two archives of queer stuff in Kentucky, and the initial basis of the collection was just a bunch of stuff that belonged to Bob Morgan, who's one of the people that the archive is named after. It's strange in that way, where it's just his house that’s full of shit that’s important to the queer community in Lexington because he has been collecting it for 40 years. So you’ll be digging through Bob’s attic because Bob has everything. He is the direct descendant of this important queer lineage here who have been outwardly and flagrantly queer in Lexington since the early 1900’s.

LG: Talk to me more about you as an independent researcher and writer. How would you characterize yourself as a professional?

PB: Yeah, I think it's very much in development. It’s an interesting time for me right now because I've spent the last three years primarily in a curatorial role, and only writing on the side. And I think that's going to flip. I think that my interests will remain consistent, with a focus on queer and self-taught practitioners from the South. That is what I have written about up until now and I think that'll continue to be the case. But right now I'm figuring out what it even means to be someone who writes full time.

LG: To that end, you’ve just been awarded one of the Arts Writers Grants from the Andy Warhol Foundation, which is a huge honor. What are the kinds of things you want to focus on or accomplish through this project?

PB: The project that I applied for was again regional, so it's focusing on the Southeast, and still with an emphasis on queer and self-taught folks. So, the region that I've outlined for myself is 12 states – Kentucky, Tennessee, West Virginia, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, and Louisiana. It's a year-long grant and I'm hoping to spend about a week in each state. I'm not sure exactly what I'll be producing or who I'll be talking to, but I'm hoping to get a kind of survey of the region over that time.

LG: Is there anything on the calendar already for you, or any particular site you're excited to go look at through this project? Or is it still really feeling open-ended?

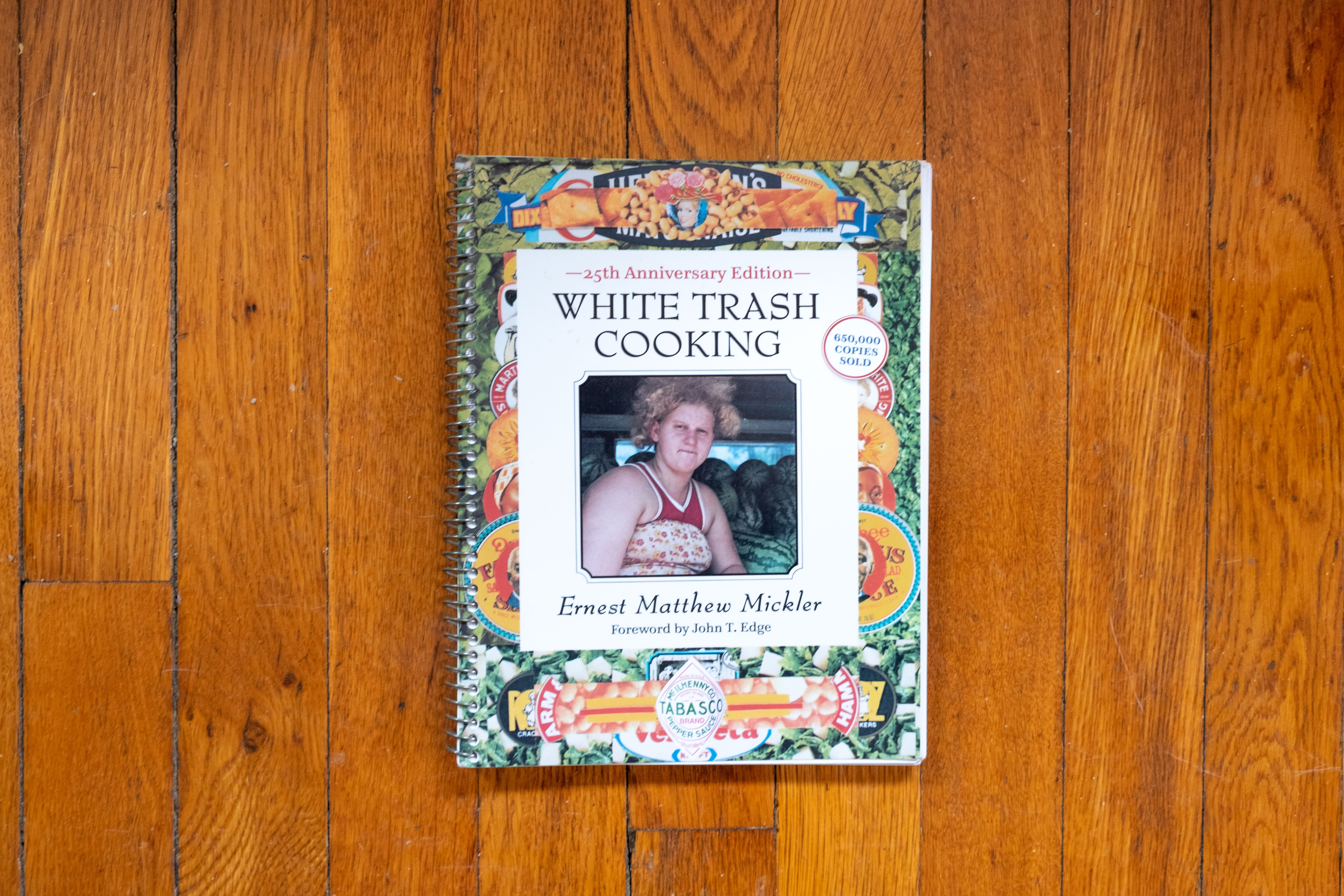

PB: It's feeling very open ended, but there are some artists' papers that I want to look into. For example, like Ernest Matthew Mickler who was a cookbook author and photographer from North Florida who wrote a very famous cookbook, called White Trash Cooking, in 1987. He was an out, flamboyant gay guy in rural North Florida who died of AIDS in 1989 and was otherwise just an interesting character. His life and work in cooking have been thoroughly looked at, especially recently, but his photographs have not been paid proper attention. So I'd like to go see his papers. They're held at one of the universities in the University of Florida system.

LG: We've zoomed in on both Lexington and the Southeast, more broadly, in this conversation. Are there any larger trends or individuals or institutions in the art world that you're excited about? Something that you feel people should be paying closer attention to right now?

PB: Well, I think I’ll have to just keep talking about the South, I guess, because I feel it to be a really interesting time to be doing creative work in the region. There's a lot of renewed attention to the region, for a lot of reasons. I think partly that’s because it's at a kind of crux of the current political situation. It’s also an extremely diverse and sometimes troubled region, and curators from larger cities are starting to recognize the value that has been there for a long time. There's a push to understand and retroactively study art from the South, especially, for instance, a lot of self-taught black artists. There's just a renewed interest in that work, even though it has always been deserving of the kind of scholarly recognition and praise that is being newly heaped on it. There's a growing understanding that the South and Southernness is just as contemporary or relevant as any other geographic region. And that is very exciting to me.

-

Notes:

L Autumn Gnadinger

Print & Digital Content Editor

3.4.20

View of facade, Institute 193 in Lexington, KY. Image courtesy of Institute 193.

View of facade, Institute 193 in New York City, NY. Image courtesy of Institute 193.

Stephen Varble: An Antidote to Nature’s Ruin on This Heavenly Glob, David Getsy, Institute 193. Image courtesy of Institute 193.

Brown’s personal copy of White Trash Cooking, Ernest Matthew Mickler.