SPEAKING: Sophia Louise Goodpasture

Q&A

Jessica Oberdick

Originally from Virginia, Sophia Louise Goodpasture is a third year MFA candidate at the University of Kentucky. Her current work focuses on creating realistic representations of found quilts. Recently, we spoke on the phone to discuss her series For Fear the Name Should Die Out and how she uses line and negative space to represent themes of identity, tradition, and memory within her drawings.

Jessica Oberdick: I wanted to ask about your current series of works For Fear the Name Should Die Out? Can you tell me a little more about this series?

Sophia Louise Goodpasture: Over the past two years I have predominantly been drawing quilts and working with quilts that I found from an old farm house that was left abandoned by my father’s side of the family. It had all these moth-ridden quilts that my grandmother had had. She wasn’t really a quilter; she did a lot of tatting, but she was in a kind of folk artists community, so I suspect that she traded her tatting for these quilts. Overall, I was haunted by the loss of narrative these materials held when I was pulling them out and looking through them. It felt really overpowering in terms of the lost rhetoric or hidden rhetoric that was embedded in quilts. Because, yes there are specific quilting patterns but it’s always a spin on each artist’s or craftperson’s perspective. Also the visceral nature of the quilts and how it is an object of comfort was really important to me. Over the past two years I have moved from obsessively archiving them—I originally started that series wanting to have an accurate representation of what the quilts looked like—and from there it has become more about folding them over and turning them into landscapes or to resemble some kind of body. And right now I am toying with what is more important to me: the idea that these quilts could be a landscape, or larger sense of a home, or native place of comfort. Or do I want it to be more about embedding a person in it? Not necessarily a figure but the emotive tension of an identity within the quilts.

JO: I like how you describe this feeling of being haunted. When I was looking at them I did find them comforting in a way, but there is a certain discomfort as well. Are there specific emotive qualities you are trying to achieve that you want the viewer to experience?

SLG: For me I think it kind of comes down to incorporating line over color. Thinking about the line as a strand. So quilts are pieces of cloth stitched together but I like the idea of separating that piece of cloth even further and the idea of tattering. I think articulating something falling apart through line is really interesting. And seeing the quilts is really fascinating. The quilts that I was lucky enough to extract from that farm house all were moth eaten and had these—I think—gorgeous imperfections, kind of like mice bites and things and they felt very wounded to me. So they felt like not only a narrative that is unknown and isn’t knowable but also felt like something that’s been degraded. That notion felt very emotive to me.

JO: I wanted to ask about your use of negative space and how you work with the fabrics to inform your compositions.

SLG: In For Fear the Name Should Die Out I was trying to balance how to do these eight-foot-tall drawings and get enough information but not too much, so trying to allow the negative space to have just as much presence as any mark. I find that that is a very difficult and nuanced thing to do. But overall, I think for me the negative space is a visual representation of a story not known. So the idea that these things can dissolve into something that is unseen is really what is fascinating and how to get the viewer to be more immersed in what isn’t there.

JO: You mention memory a couple of times in your artist statement regarding the falsity of memory and also memories of tradition and community with quilt making. Can you talk a little more on how you work with memory in the work as well?

SLG: I think quilts as a material are really fascinating with the idea of memory because they are made to be handed down or gifted a lot of the time. Or they are given to you to put on a bed to keep you warm. And within them they carry the memory of the maker. And it is a push and pull of whether or not that is relevant. So there is the memory of the maker and everyone who uses it and kind of like the aspects of their life they bring to it. So whose memory or narrative has importance? Also the material itself is pretty fragile—you can disintegrate cloth pretty easily and it carries that memory. Maybe it is not as direct as clay that can hold memory with its substance, but cloth carries smells, it carries all of these things we don’t necessarily associate or give power to. Again back to the negative space. I think what is really fascinating is the hint that it carries more than you could understand.

JO: So you have been working on this series for about two years? Can you talk about its development? I saw you had some more figurative work on your website as well.

SLG: Yeah it has been mainly the past two years. Originally, I was trained as a figurative artist and worked with the figure but I had a really difficult time aligning myself with art history and the sense of proliferating the male gaze that I wasn’t comfortable with. I am really drawn to female narratives because I identify as female and I grew up in a more direct matriarchy as opposed to patriarchy with my particular family so I wanted to have conversations about my personal experiences and the people who influenced them, but it always felt like it was seen through the eyes of the male gaze which made me really uncomfortable. So having the quilt as a medium to possibly have those conversations really excites me.

JO: How do you see this work evolving?

SLG: I am really excited. I don’t know if I will ever stop working with quilts. I am really fortunate being tied to a university. I get to have so many conversations with different people and it’s kind of like whiplash because the work I do is really meticulous and takes a really long time to make but I can have a conversation with someone in half an hour and be like, “oh my gosh, now the work is about landscapes,” or pre-territories, imaginative wonderlands, or they could be really clear depictions of identity or identity dissolving or identity closing in on itself. And I think right now I am in the position where I need to more clearly align what I want my series to be.

-

Notes:

-

12.13.2020

Jessica Oberdick (she/her) is an independent curator and writer whose research focuses on themes of identity and social perception. She currently works as the Exhibitions Assistant at the University of Louisville.

Square Quilt, 2020, Graphite on Paper, 30" x 22"

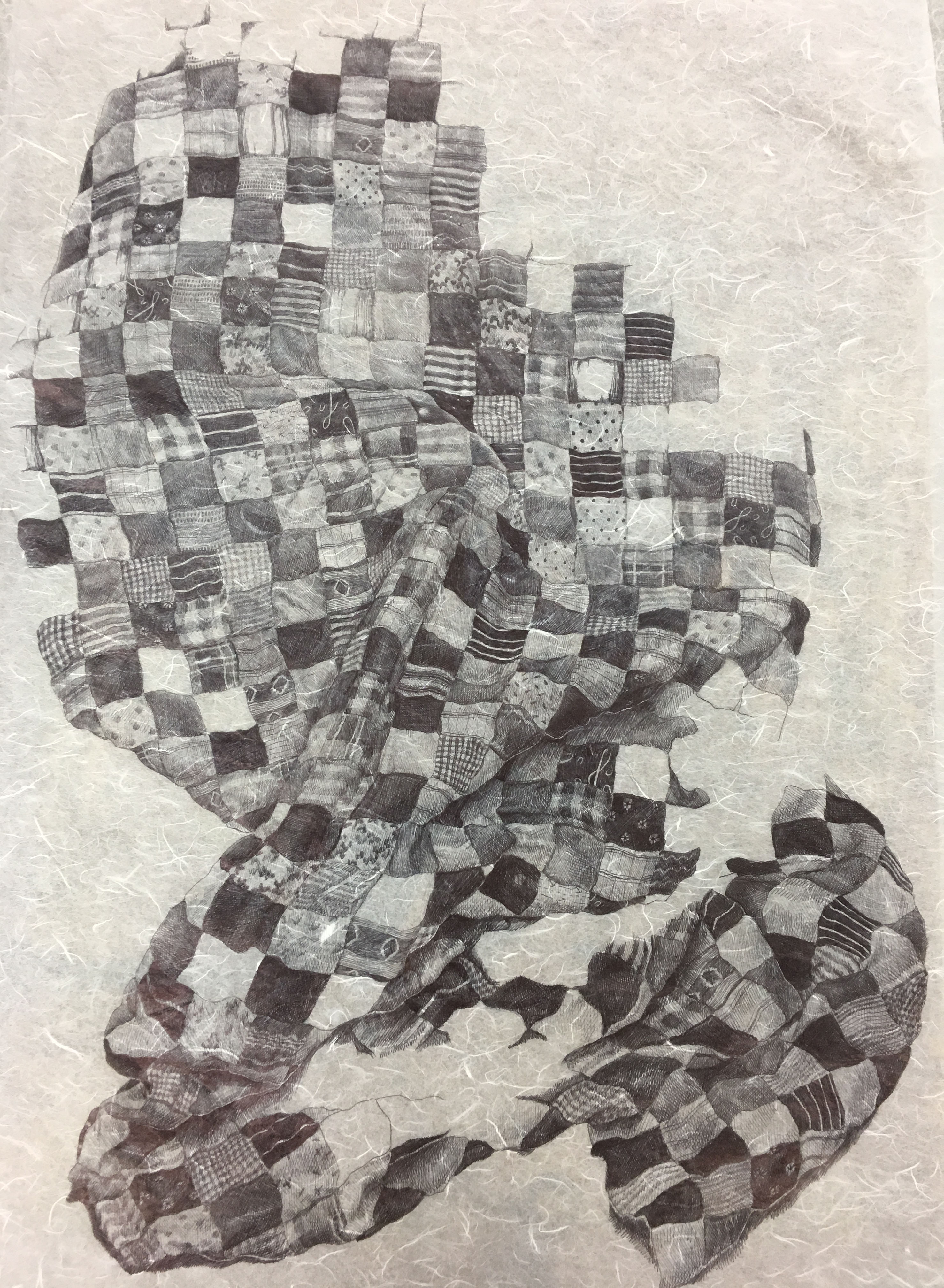

Tattered Seams, 2020, Bic Pen on Paper, 36" x 36"

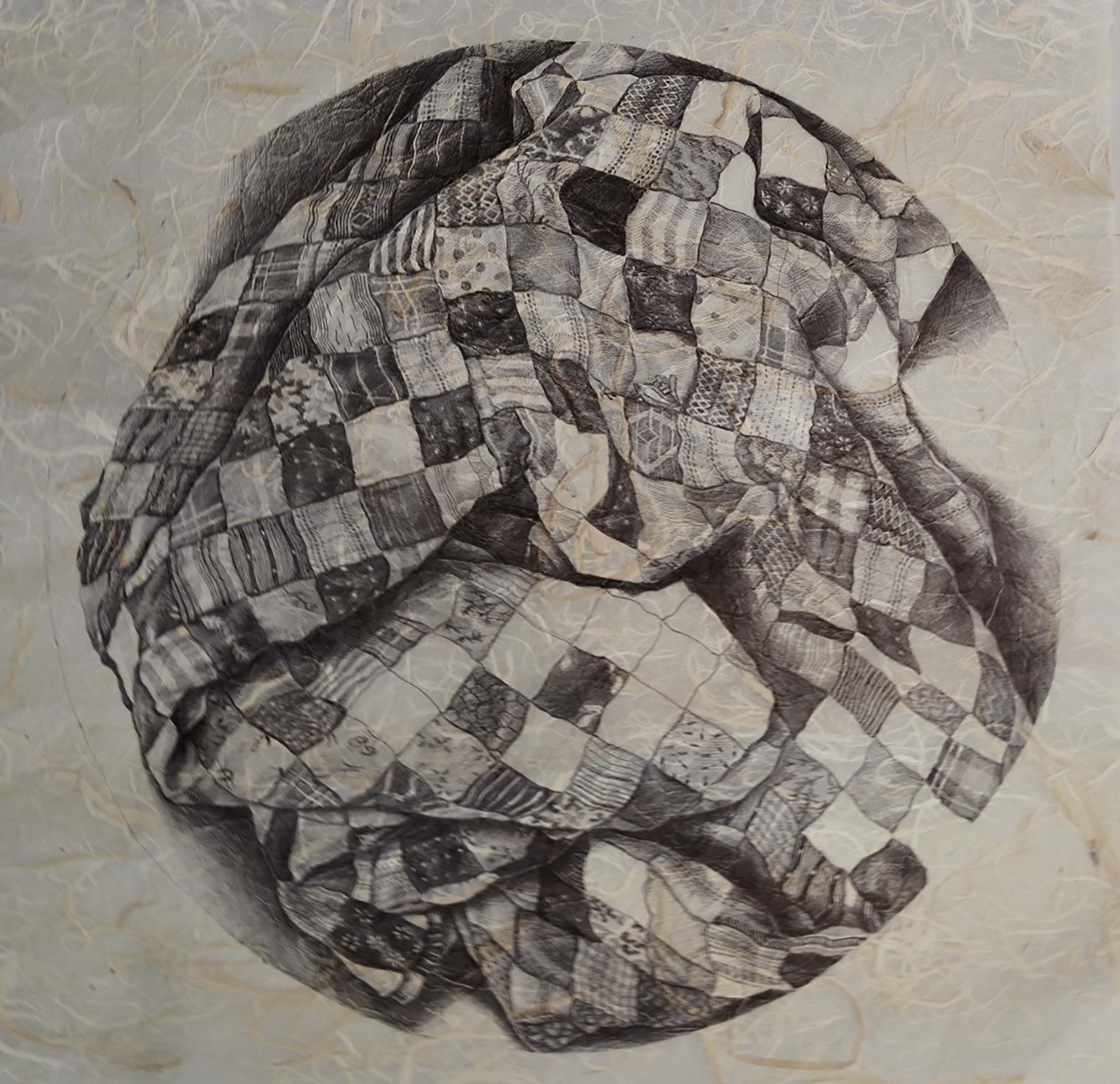

Tightly Wound, 2020, Bic Pen on Paper, 36" x 36"

Encased Histories, 2019, Bic Pen on Paper, 30" x 22"