ABOVE: Sara Olshansky, Memorabilia: Assemblage #2 (2023), air dry clay, oil on air dry clay, assorted fossils from Louisville tributaries from Joe Johnson’s collection, dimensions variable. All photos courtesy of Blake McGrew.

Then is Then For the Both of Us

Review

Kevin Warth

Then is Then For the Both of Us is an exhibition that rewards investigation and diligence. Sara Olshansky’s work is spread along the walls, across the floor, and in high corners of houseguest gallery—experiencing every detail requires one to crane their neck or even get on the floor. This labor mirrors memories, much like the psychic act of digging deep within our own minds to pull certain experiences to the forefront. Utilizing found objects, energetic linework, and a variety of techniques, Olshansky finds immense potential in the natural world to explore the possibilities and limitations of human memory.

Rendered in a breadth of media such as graphite, painting, photography, cast resin, and found objects, fragments of plant life, faces, and sky coalesce into a hazy, fractured vision that can perhaps only be fully understood by the artist herself. Remnant #3 (2023) consists of many erratic lines that draw one’s eye across the piece. Towards the bottom, olive greens, browns, and sky blues suggest a landscape that is interrupted by sections of bright white paper and rich black charcoal. The lines do not depict something immediately identifiable, but instead ask, “What is missing?”

Olshansky cuts shapes into the surface that rupture her rendered environment with images and fragments of the physical world, such as collected rocks or photographs of tree bark and sky. The artist is careful never to give away too much—these windows only allow viewers access to a small portion of the larger image. Mementos appear elsewhere, with pictures, rocks, seeds, and other found objects cast in resin such as in Assemblage #1 (2022-23) and Water Tile (2022). Hung at high sight levels throughout the gallery, small, painted pieces of clay act as slivers of sky. The interplay between these works and others is delightful, as if sections are detaching and floating away. Through these materials, Olshansky creates a rich environment for viewers to consider their own experiences, relationships, and fractured memories.

Olshansky opens her artist statement with the following assertion: “Memory defines human perception of the world.” This holds true when considering the myriad ways in which one’s life is built upon their past experiences. A negative visit to the doctor may color all future appointments. A certain type of perfume may induce positive, sometimes nostalgic feelings. Even though memories hold such a vital role in one’s perspective, they are also deeply flawed. A study conducted by neuroscientists Donna Bridge and Ken Paller revealed that memories become distorted with each recall, not unlike a game of telephone.1 Then is Then For the Both of Us elucidates this concept through a number of methodologies. While some of the objects and photographs cast in resin are clear, others have a hazy and translucent appearance that blocks part of the viewer’s access. Likewise, the cut-outs of the works on panel provide meager windows to see underneath, leaving much of the imagery inaccessible. These techniques mirror the ways in which our memories degrade over time, rendering that which we recall less and less reliable.

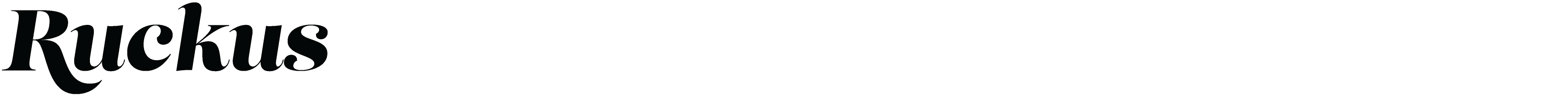

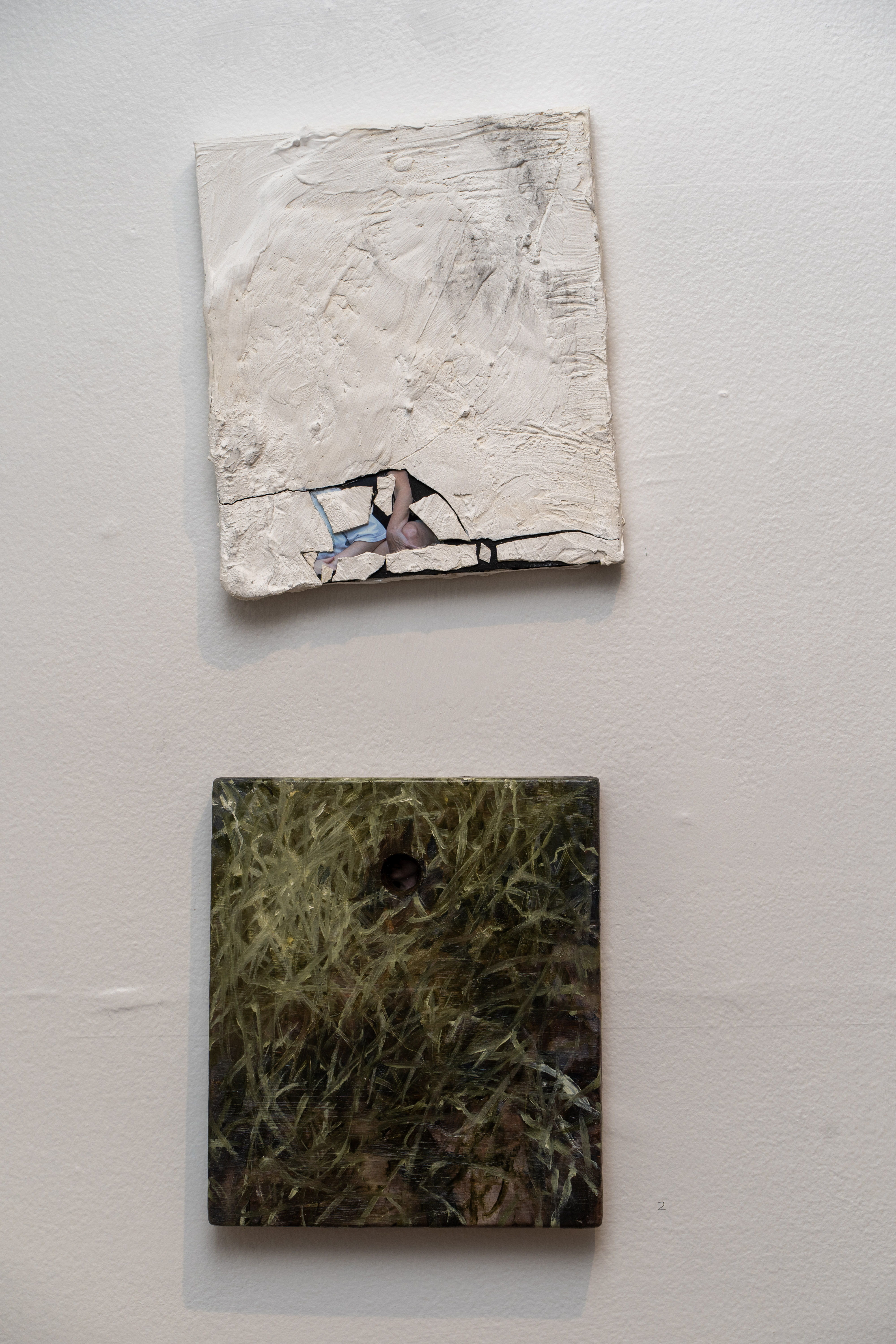

For many, cherished memories take the form of holidays, vacations, and milestones like graduations or weddings. Olshansky, however, turns to imagery relating to the natural world, specifically photographs from her home garden. In doing so, she connects memory to the cyclical nature of growth and decay. Memories will eventually fade in one’s mind but, to quote the artist, “they fertilize the grounds for richer experiences to take place on their site of decay.” Striking for its sparseness, Family Portrait #1 (2023) expresses this deterioration unlike any other piece in the exhibition. The photograph–depicting fragments of bodies, specifically two arms and a knee–lies beneath a layer of plaster; it is as if the image has been partially excavated. While the rest could be seen as dead space, the detail Olshansky has imbued in it ensures that, to follow the aforementioned metaphor, it is fertile ground. The texture of the plaster lends itself to interesting bumps, crevices, and textures that encourage the eye to wander and take in the minute details. Moreover, marks on the surface add to the richness of the material. These moments throughout Then is Then For the Both of Us act as welcome space for new memories to be made.

Spread across a windowsill and the gallery floor, a curious mixture of real fossils and faux creek rock further expand on themes of time, memory, and nature. The latter are immediately recognizable as artificial due to their bright white color. In spite of the rock’s abundance in nature, Olshansky creates them out of white clay in highly specific shapes. This practice draws parallels with memory: oftentimes, the recollection of certain events can cloud one’s perception of the world around them, superseding any sort of truth.

While many see fossils as an irrefutable window to the past, they too have ontological shortcomings. Fossils form when sediment covers a dead organism, and bone or shell harden into rocks. They are, thus, the environment’s interpretation of the creature that once lived, a memory of the earth. By including these in the exhibition, Olshansky encourages the viewer to consider memory on both a personal and monumental scale. Even long after the last human has passed, memories will persist in other creatures, in the land, and even in a more spiritual or ethereal manner. Scholars Christopher Castiglia and Christopher Reed surmise that memory “takes on a simultaneously somatic and salvific capacity to retain life after the body that experiences has passed chronologically beyond the moment.“2 Just as plants put out seeds to extend the life and reach of their kind, humans collect and make memories, ensuring their own form of futurity.

-

Citations:

- Citations:

Donna J. Bridge and Ken A. Paller, “Neural Correlates of Reactivation and Retrieval-Induced Distortion,” Journal of Neuroscience 29, no. 32 (August 2012): 35. - Christopher Castiglia and Christopher Reed, If Memory Serves: Gay Men, AIDS, and the Promise of Queer Past (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011): 15.

-

6.28.23

Kevin Warth (he/him) is a Louisville-based artist and art historian whose research emphasizes queer identity, alternate temporalities, and hauntology.

Sara Olshansky, Remnant #3 (2023), graphite, charcoal, and oil on panel with creek rock, collage, and polaroid cast in resin, 23x16.”

Top: Sara Olshansky, Family Portrait #1 (2023), family photograph, plaster, and acrylic paint on wood, 9.5x8.”

Bottom: Sara Olshansky, Family Portrait #2 (2023), family photograph and oil on paint on wood, 9.5x8.”

Bottom: Sara Olshansky, Family Portrait #2 (2023), family photograph and oil on paint on wood, 9.5x8.”

Sara Olshansky, Assemblage #1 (2022-2023), mixed media and collected objects cast in resin, dimensions variable.

Sara Olshansky, Assemblage #1 (2022-2023), mixed media and collected objects cast in resin, dimensions variable.

Sara Olshansky, Sky Remnant (2023), oil on air dry clay, dimensions variable.