Trading Trauma: An Art Exchange

Essay

Marlesha S. Woods

We do not choose what harms us but we can choose to navigate pathways that heal. One of the healing agents of contemporary thought is the arts. Could this creative expression be a form of salve treating the human condition? According to the Director of Arts and Mind Lab of Boston College Dr. Ellen Winner, “While we may not need art to survive, our lives would be entirely different without it. The arts are a way of making sense of and understanding ourselves and others, a form of meaning-making just as important as are the sciences.” During a Q&A facilitated by the Harvard Gazette, Dr. Winner explained, “It’s interesting to note that the arts have been with us since the earliest humans — long before the sciences — and no one has ever discovered a culture without one or more forms of art.”

Modern plights of dissension among intercultural relations could be approached with an increased use of the arts to uplift more commonalities than differences. When one considers the universal language of art, the transformative result of its implementation is equivalent to a translator, bridging information and nuance amid disconnected people. Art as a process and of a point of cultural entry requires all people groups to consider lived experiences as expressions of a larger reality, one of community, and collective interactions. When art happens diversity happens.

Unlike voyeurs prosulating the meanings of motifs within paintings, the mindshift to become participants instead of solely observers within the arts has created an interplay among producers and consumers. Artists both visual and performing are inspired during live painting and music creation for example, just as much as an audience is moved by their intricate works. The relationship between how art is created and why it is rendered is strongly tied to emotional responses from people that may not be directly connected to the art industry, yet are still impacted.

Art can evoke rage, tears, happiness, a myriad of physiological responses that link neurological connections of sensory stimuli to memories of lived experiences. According to writer Robert Lee Hotz:

“When it comes to art, beauty may be in the eye of the beholder, but some scientists now are looking for it in bursts of brain waves.

Seeking a biological basis for our response to art, researchers from the University of Houston recorded the electrical brain activity from 431 gallery visitors... as they explored an exhibit of works by conceptual artist Dario Robleto at the Menil Collection, near downtown Houston. In the low-voltage sizzle of so much neural buzz, the scientists are trying to find how our brains mix sensory impressions of color, texture and shape with memory, meaning, and emotion into an aesthetic judgment of artworks that, at their best, can be both universal and intensely personal.”

The same movie score that makes one film lover cry could leave another person completely unbothered. Pivoting from the “why” of the significance of visual art leaves researchers with an undesirable resolve of human exploration with limited answers to it’s brain effects. Instead of relying on researchers alone to shed light on the transcendent nature of visual arts, a consideration for context provided by artists can illuminate the symbiotic relationship among art creation and art consumption.

Louisville artist Auzzie Dodson “believes that art is physical and should be used to unify/build communities. Art is a weapon and must be used by any means necessary.” The statement appears a bit contradictory when considering the act of building unity juxtaposed to the brash phrasing of weaponry. In retrospect, the majority of peace brought into this world from community catalysts have utilized art in some form. Those that have been historically resistant of the healing that art provides have seen art as a thorn in society’s side. Auzzie accurately depicts the empowerment that art can bring, which in recent years the U.S. particularly has seen more of in response to social outcrys for justice. Through an unprecedented pandemic, citizens have used visual and performing arts globally to elevate peaceful protests, challenge political mayhem, and most intimately combat COVID19 anxieties by tapping into more creative outlets.

The phrasing outlet sums up the concept of connecting interdisciplinary art with psychological responses. To seek an outlet one must address the binary reality that people are inevitably demanding to be figuratively let out, and in many cases that liberation is an escape from past trauma, grief, and in todays’ climate chaos. Creating works of art for personal satisfaction trades pain for a bit of peace.

Educator and interdisciplinary artist Louis Netter divulges:

“People are dying, critical resources are stretched, and the very essence of our freedom is shrinking—and yet we are moved inward, to the vast inner space of our thoughts and imagination, a place we have perhaps neglected. Of all the necessities we now feel so keenly aware of, the arts and their contribution to our well-being is evident and, in some ways, central to coronavirus confinement for those of us locked in at home.”

Through social isolation humanity is stuck in a simultaneous loop of routine and uncertainty, all shockingly triggering even the most stoic individuals. Temporarily—and in some cases permanently—severed from loved ones, there is an ever growing need to break the loop and reset the soundtrack of our lives. Art does that. Despite this, creating art through introducing simple drawing exercises, free verse writing, tapping into poetry, dance, painting, sculpting, among other forms is still a mystery among scientists without full explanation to the syncopated cadence among art and its effects. Yet, “In addressing these issues, among others, society needs the work of scientists and health professionals to be informed by, and infused with, a wide range of human insight, experience and values. We need not just science but also the arts and humanities — and a union between them”, states physician David J. Skorton and psychologist Lisa Howley.

How art shapes our physical, spiritual, and emotional well being is not dependent upon the art that is created around us but the art we choose to create from within. As uniquely diverse and creative humans, we all have the ability to create some form of art, as art simply is a process of life. When we “reflect the times” as famed artist Nina Simone phrased we begin to encapsulate a reality that we subsequently hope to improve. There is no doubt that more art forms, works, and channels are being explored since the global pandemic and social justice protests have erupted. One can only wonder: is the influx of art in the world a holistic and human-made medicinal response to trauma? Many of us are choosing to reconcile by exchanging our collective pain with the healing attributes of art.

-

Notes:

- The Aesthetic Attitude to Art

- Researchers Observe Effects of Art on the Brain

- Auzzie Dodson

- Art Matters More than Ever During the COVID-19 Crisis

- Why we Need the Arts and Humanities to Get Us Through the COVID-19 Pandemic

-

5.15.21

Marlesha S. Woods (she/her) is a dedicated visual artist, visual storyteller, creative placemaking strategist, writer, community researcher and visual arts educator from Louisville. Pairing visual arts with advocacy Marlesha has partnered with non-profit organizations nationally within the U.S. to strengthen communities and spark vital conversations including health equity, diversity and civic rights. Her visual artistry includes wearable art, commissioned paintings including a focus on abstract expressionism intertwined with portraiture.

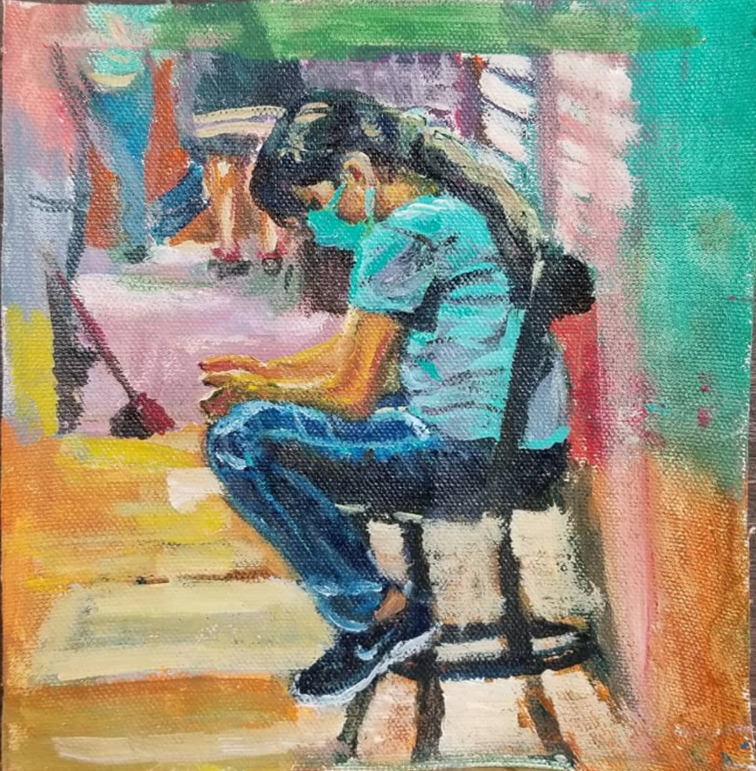

Niña en el Mercado, Manuel Hernandez Sanchez. 2020. Acrylic on canvas.

Reference Photo by Patricia Castellanos.