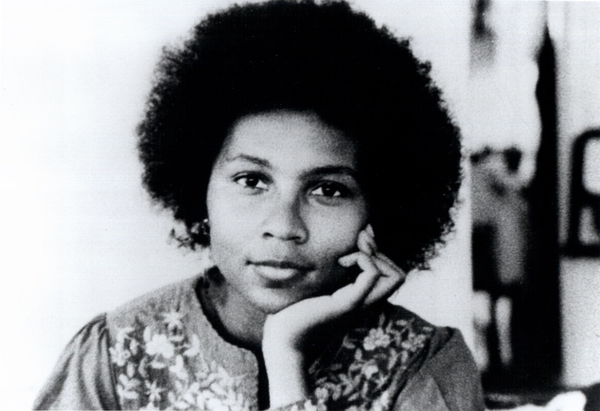

We Will Continue to Learn: Remembering bell hooks

Essay

“Contemplating death has always been a subject that leads me back to love. Significantly, I began to think more about the meaning of love as I witnessed the deaths of many friends, comrades, and acquaintances, many of them dying young and unexpectedly.” (2000: xxii)1

bell hooks’ passing feels personal to so many of us. I sit with the grief, knowing that she, like so many other Black feminist artists, writers, and activists, left this world too soon. I think about the health conditions that caused Audre Lorde to die at 58, June Jordan at 65, Barbara Christian at 56, and how that may have been exacerbated by the structural violence each faced during her lifetime. Grace Hong names these women, among others, as she responds to James Baldwin’s call to “bring out your dead”.2 Hong writes, “To bring out your dead is to say that these deaths are not unimportant or forgotten, or worse, coincidental. It is to say that these deaths are systemic, structural. To bring out your dead is not a memorial, but a challenge, not an act of grief, but of defiance, not a register of mortality and decline, but of the possibility of struggle and survival” (2008:97).3 To bring out your dead is both an interrogation of the systems of imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy that hooks so aptly identified and a practice of love. As I process bell hooks’ death, I lift her name up against a world that creates condemning conditions for Black women and femmes to survive.

hooks’ words have echoed so clearly in my mind since I first read her writing. They move me, as she balances a voice of conviction while sharing aspects of her own life with generous vulnerability. Each piece forges a space of self-reflection, asking the reader to sit with both her thoughts and your own. The self is the starting point of growth and change. In “Toward a Revolutionary Feminist Pedagogy,” bell hooks asks us, “to see ourselves first and foremost as striving for wholeness, for unity of heart, mind, body, and spirit” (1989:49).4 I approach the journey for wholeness as a continual process focused on seeking alignment and listening to your spirit. hooks often returned to things she had written about earlier in her life, made alterations and confronted herself in the work, emphasizing that mistakes are made and can be an opportunity for growth. As a writer that honesty means so much, to give myself grace and know that the words I put to page are not static thoughts. We are always allowed to redact, revise, and transform.

In the same essay, she remarks on her favorite teacher, Miss Annie Mae Moore, who taught her while in grade school in Kentucky and employed, “a pedagogy of liberation… that would address and confront our realities as black children growing up in the segregated South…to teach us an oppositional worldview different from that of our exploiters and oppressors” (1989:49).5 A pedagogy of liberation supports the articulation of the self and gives access to the tools of critique and critical engagement. hooks emphasizes pedagogy as a site of possibility to make meaning of one’s experiences amidst discourses that seek to marginalize difference. The importance of this pedagogy for Black folks in the U.S. South was evident, as was her love for Kentucky. She was the Distinguished Professor in Residence in Appalachian Studies at Berea College and maintained that the South will always be a site of invaluable knowledge.

She was an artist and visual critic who understood art as integral to pedagogy. hooks urged Black folks to embrace creativity, giving ourselves permission to experiment and engage with art as a “practice of freedom”. In Art on my Mind, she pushes us to see differently, writing, “For more black folks to identify with art, we must shift conventional ways of thinking about the function of art. There must be a revolution in the way we see, the way we look” (4).6 That revolution will always be spurred by questions, attending to the ways art makes us think and feel. She signals art not just as a product through creation, but as modes of envisioning what cannot yet, or should not be defined.

When I learnt about her passing, I immediately texted two of my close friends, Michell and Candice, or the bell hooks’ aunties as we often referred to ourselves. For us, it was hooks’ investment in ethics and grappling with real world material impacts that always resonated. She believed in the power of theory to provide frameworks to better comprehend the world we live in and to serve as scaffolding to build the world we want to see. For hooks, abstract concepts and everyday life are always intertwined, flowing into each other. In “On Self-Recovery”, she writes, “All theory as I see it emerges in the realm of abstraction, even that which emerges from the most concrete of everyday experiences. My goal as a feminist thinker and theorist is to take that abstraction and articulate it in a language that renders it accessible—not less complex or rigorous—but simply more accessible” (1989: 39).7 Her commitment to writing that welcomes a range of readers and the belief that theory emerges from everyday life are political stances which hooks reiterated throughout her life.

bell hooks is a Black queer feminist who understood that queerness extended beyond thinking about sexuality and desire, towards a more expansive understanding of the erotic as interrogating the oppressive confines of “normativity” and individualism, thinking alongside Audre Lorde. In her 2014 discussion “Are You Still a Slave? Liberating the Black Female Body,”8 a conversation with Marci Blackman, Shola Lynch and Janet Mock, hooks explained, “queer not as being about who you’re having sex with—that can be a dimension of it—but queer as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it and it has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live.” She positions queerness as a politics of difference that questions power structures, connecting varying experiences of marginalization and is ever shifting. For hooks, as Candice beautifully shared in our conversation, queerness also manifested as an investment in the sensuality of relation, whether that be romantic or friendship.

Recently, I taught a course about Black Feminist perspectives on intimacy, and I included sections of All About Love. We discussed difficult intimacies, meditating on what it means to be in relation to others while living amongst loss, violence, and histories of pain. hooks asks us to face these challenges of relation and turn to love as a way to move through and alongside the traumas we hope to heal. She writes, “when we choose to love we choose to move against fear—against alienation and separation. The choice to love is a choice to connect—to find ourselves in the other” (93).9 Cultivating love is not an antidote to pain and violence, but a key to envisioning other ways of living that prioritize collective wellbeing through practices of care.

bell hooks will always be present in my life and inform my Black feminist politics. Her sense of humor often comes through her work and the way she cut-up with Cornell West as part of her Transgression series is a reminder that in a world of immense trials, we must find space to laugh.10 As she remarked in her interview with George Yancy, “Humor is essential to the integrative balance that we need to deal with diversity and difference and the building of community.”11 hooks viewed curiosity as a gift and affirmed that we each have the power to interrogate oppressive forces. I am grateful for the chance to bring together this collection of notes and consider the ways her work has impacted other writers, scholars, artists and activists.

The editorial team asked writers in the Ruckus community to share a bell hooks text that resonates with them. Below are their offerings, reflecting on the expansive impact hooks’ work will continue to have:

John Brooks

The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love (2004)

“Learning to wear a mask (that word already embedded in the term “masculinity”) is the first lesson in patriarchal masculinity that a boy learns. He learns that his core feelings cannot be expressed if they do not conform to the acceptable behaviors sexism defines as male. Asked to give up the true self in order to realize the patriarchal ideal, boys learn self-betrayal early and are rewarded for these acts of soul murder.”

This immediately resonated with me when I read it a few years ago because from a very early age I felt like I had to wear a mask in order to conform to what was expected of me. My core feelings could never be expressed—quite the opposite, yet despite innumerable signals telling me I wasn't really a boy or a man—or at least not a good one—I felt like one, in my own way. It was a constant struggle, deciding to betray myself or "everyone else." As a young person, I chose to betray myself, but no longer. Thankfully, definitions of masculinity have expanded and still are expanding. That's something I am concerned with in my own work, and I'm grateful for bell hook's brilliance and foresight. She will be missed, but her words live on.

L Autumn Gnadinger

“Theory as Liberatory Practice” from the Yale Journal of Law & Feminism 1 (1991-1992)

bell hooks’ essay “Theory as Liberatory Practice” stands out for me, as an artist, editor, and citizen, as one of the most instructive pieces of writing I’ve ever had the good fortune to read. In less than a dozen pages hooks traces the opportunities and perils of the philosophical strategies we call “theory.” She combats the “false dichotomy between theory and practice,” and plainly explains that “any theory that cannot be shared in everyday conversation cannot be used to educate the public.” For hooks, anything less than this means only to “divide, separate, exclude, keep at a distance.” It is a map that spares no complexity and takes no tool for granted—all fixed keenly on a revolutionary future and the specter of yet-to-be-imagined theories which could bring us there.

bell hooks. “Theory as Liberatory Practice”. Yale Journal of Law & Feminism 1 (1991-1992)

Brittany Thurman

Homemade Love (2002)

I would love to suggest one of her children's books, Homemade Love. I feel that bell hooks children's books too often get overlooked. They are early examples of children's literature that positively uplift Black experiences, especially that of young Black girls.

Anna Blake

Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope (2003)

While it is completely coincidental that I began reading hooks’ Teaching Community in the spring of 2020, I can’t think of a better text to have guided me through those dark months. With Teaching Community, hooks expanded on a concept by Paulo Freire: the pedagogy of hope. hooks writes: “Our visions for tomorrow are most vital when they emerge from the concrete circumstances of change we are experiencing right now.” Her essays, though shaped by the immediate post-9/11 experience, are especially germane for this post-pandemic, post-Trump presidency, post-point-of-no-return future that lies ahead. Whenever I find myself feeling hopeless, Teaching Community reels me in. In a world where the dominator culture feeds on cynicism, hooks reminds us that the most punk thing we can do is imagine a future where we thrive.

Ian Carstens

“Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance” from Black Looks: Race and Representation (1992)

Experiencing the works of bell hooks always reminds me of timeouts as a kid. Staring at shadows in a pale plastered corner, these were some of the most formative moments for me. Sure shame and guilt were present, but so were moments of deep reflection and introspection. hook's “Eating the Other” sits you down, takes things to task and does so with so much undeniable beauty and compassion. This and all her works move with a steady, critical slowness—like the movements of mountains.

Megan Bickel

Teaching to Transgress (1994), All About Love (1999), “Critical Reflections” from Artforum (November, 1994), Art on my Mind: Visual Politics (1995)

I've spent several days considering where I discovered bell hooks and how and why she impacted my way of thinking. I can't fully resolve or compress it to a specific reading. bell hooks' authorship coagulates my creative processes. Teaching to Transgress (1994) is one of the key readings that helped me realize learning (being infinitely curious) was a superpower we all possess and can utilize to contribute to the empowerment and stabilization of our communities. All About Love (1999) taught me how to re-prioritize this abstraction called love, re-learn genuine compassion, and the labor of restoration in a real way after my divorce. Her words aided in constructing the parts of myself that I am in most love with.

During my time at the Art Academy of Cincinnati in the early 2000's, I frequented the downtown branch of the Cincinnati Public Library. Enamored with their extensive collection of Artforum's, I stumbled onto bell hook's contribution to the November 1994 issue. hook's gift, an essay on her frustrations regarding dispassionate cultural criticism was, in retrospect, where my lustful quests for understanding visual or cultural ephemera originated:

An excerpt:

Writing is my passion, a way to experience the ecstatic. The root understanding of the word "ecstasy," "to stand outside," comes to me in those moments when I am immersed so deeply in the act of thinking and writing that everything else, even flesh, falls away. However, the experience of language as a transformative force was not something I arrived at through writing. I discovered it through performance—dramatically reciting poems or scenes from plays. Our all-black, Southern, segregated schools valued the art of oration. We were taught to perform. At school and at home we entertained each other with talent shows—singing, dancing, acting. Seduced by the magic of words in childhood, I am still transported, carried away, writing and reading...I want to be sure I am grappling with language in such a way that my words live and breathe, that they surface from a passionate place inside me…Had I entered my writing life as a critic, working this way might not have mattered to me. Instead, I began by writing poems.12

Her authorship instituted her pedagogy. Over the years, I fantasized about meeting her during some quiet lecture one humid mid-week evening in Berea, Kentucky. Her choosing to teach where her mind felt quiet and supported was an inspiration.

Another excerpt, from Art on my Mind: Visual Politics (1995):

"Displacement involves the invention of new forms of subjectivities, of pleasures, of intensities, of relations, which also implies the continuous renewal of a critical work that looks carefully and intensively at the very system of values to which one refers in fabricating the tools of resistance.”13

At a pivotal point in my life, around 19 or 20, bell hooks notified me that my perspectives as a child experiencing housing instability, an insecure family structure, and sexual abuse compelled me to try to help in a way that my education would never afford me. Nor was it able to. And perhaps it shouldn't. Though I felt isolated, scared, and misunderstood, I had the power of a different kind of subjectivity that would provide for me for the rest of my life. I am profoundly grateful that in her writing about her own experiences about race, gender, poverty, and education, I was able to see that I had things to contribute.

bell hooks will be admired, cherished, and missed deeply for an eternity, but I'm confident that her thoughts will afford her centuries of time travel.

Marlesha S. Woods

After watching a series of bell hooks’ interviews I became more acquainted with her body of work. Although, her work appeared more like purpose than ancillary draws of income. The word work just doesn’t seem to fit. The impact of bell hooks ironically like a bell resonates with many, whether intimately aware or only connected loosely, like myself through voyeurism.

bell hooks tackled some of the most complex issues of our time before hers. Or, is there really such a thing as before or after “our anything.” As we do not own space, or time, or the actions and reactions of people for that matter. We have the right to respond to our lived experiences and seek to learn how to love.

Her courage to pursue love and seek to better understand the navigation of love amplified her story and the countless stories by those that felt unloved around her.

I hope she found what she was looking for.

-

Citations:

- bell hooks. All About Love: New Visions. Harper, 2000.

- James Baldwin. The Evidence of Things Not Seen. Henry Holt, 1985.

- Grace Kyungwon Hong. “‘The Future of Our Worlds’: Black Feminism and the Politics of Knowledge in the University Under Globalization.” Meridians, Vol. 8, No. 2, 2008.

- bell hooks. Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black. South End Press, 1989.

- bell hooks. Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black. South End Press, 1989.

- bell hooks. Art on My Mind: Visual Politics. The New Press, 1995.

- bell hooks. Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black. South End Press, 1989.

- bell hooks. “Are You Still a Slave? Liberating the Black Female Body.” Public Discussion at The New School, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rJk0hNROvzs&ab_channel=TheNewSchool

- bell hooks. All About Love: New Visions. Harper, 2000.

- bell hooks. “A Public Dialogue Between bell hooks and Cornell West.” Transgression series at The New School, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_LL0k6_pPKw

- George Yancy and bell hooks. “bell hooks: Buddhism, the Beats and Loving Blackness.” Opinionator in The New York Times, 2015.

- bell hooks. “Critical Reflections.” Artforum. November, 1994. p 64-5. Accessed December 2021. https://www.artforum.com/print/199409/critical-reflections-33323

- bell hooks, Art On My Mind: Visual Politics. The New Press, New York, New York. 1995. p13. https://monoskop.org/images/7/7b/Hooks_Bell_Art_on_My_Mind_Visual_Politics_1995.pdf

-

2.3.22

bell hooks