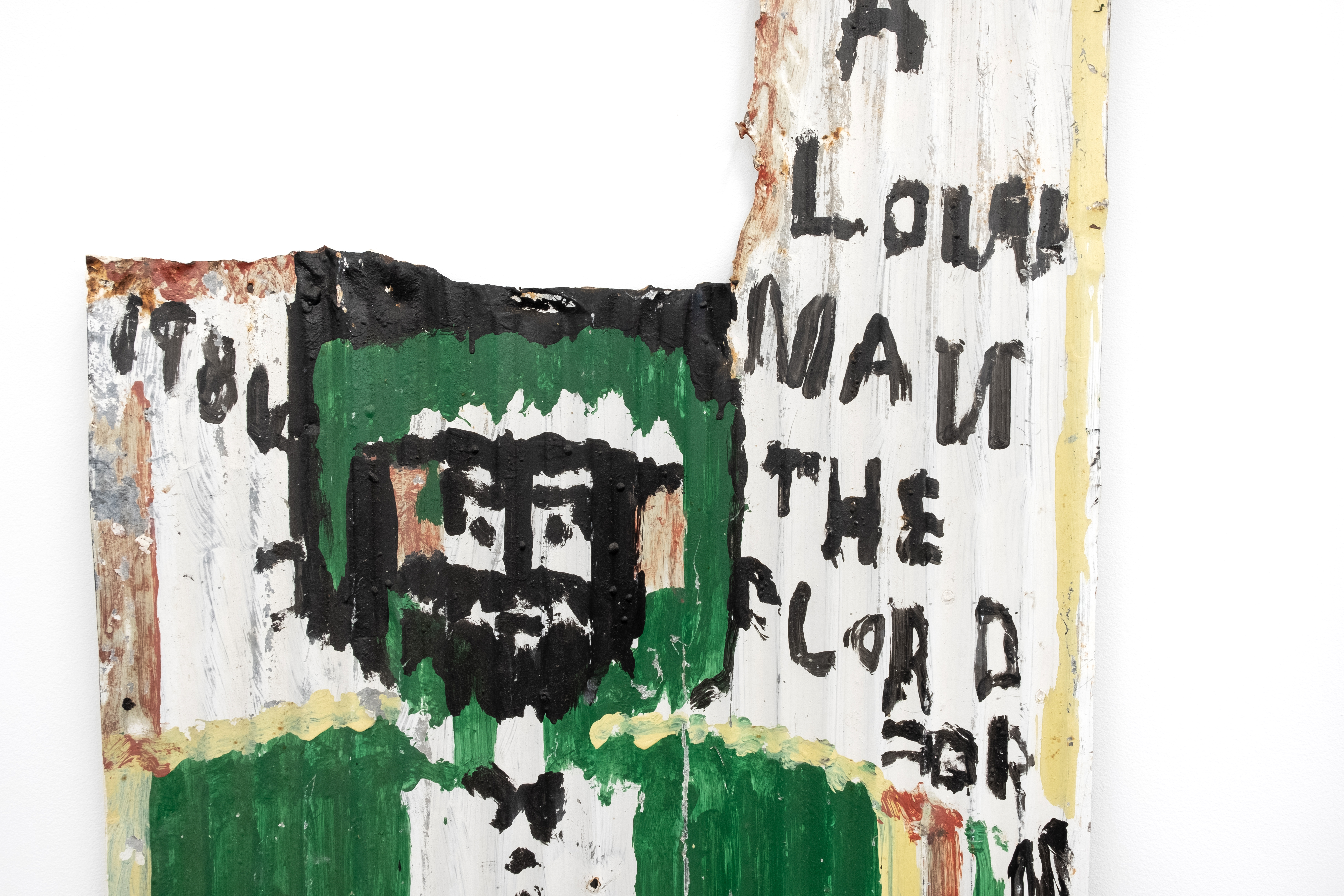

Above: Mary Tillman Smith, various works (1984).

︎ KMAC Museum, Louisville

Where Paradise Lay: Art and Southern Sanctuary

Review

L Autumn Gnadinger

Where Paradise Lay: Art and Southern Sanctuary is something of a homecoming for KMAC Museum. The exhibition statement discusses the organization’s 1981 roots as the Kentucky Art and Craft Foundation, and how this show features artists “directly involved with making a paradise for themselves in the front yard, the back garden, the parlor, the sun porch, the basement.” During a movement when thousands of protesters in Louisville and millions worldwide are dreaming of and demanding their own rightfully earned paradises, the summer show at KMAC has managed to offer something that does feel nice to view. But, while Where Paradise Lay succeeds in many ways it fails in others. In 2020, for a museum to deliver something that is fully urgent to see will require more than shrewd aesthetics: it will require fundamental change.

From the start, it should be said that Where Paradise Lay walks a fine line. The featured works, at least since the ’70s, would have been described by most art historians as “Outsider Art,”1 which is an English adaptation of the same, older concept in French: art brut. The latter comes from the same root as our brute, or, brutish, and in either language refers to art that is created outside of the influence of what we generally consider the “art world.” Gestures of curation that focus on “searching” for such works, or books like Walks to the Paradise Garden: a Lowdown Southern Odyssey2, which the current exhibition at KMAC is based on, are not new. Coming from the coastal centers of New York and L.A., such an approach can seem more than a little colonial. This framework, where “outsider” works are being curated by “insider” people and institutions, inherently robs such artists (who are often Black, Indigenous, other People of Color, rural, poor, neurodiverse, or disabled) of narrative agency and continues to position a—usually White—“discoverer” as both the hero and the default storyteller.

Given Louisville’s ostensible Southern identity and KMAC’s unique position as the inheritor of many craft-focused works in its collection, Where Paradise Lay at least feels overtly earnest; pleading, even. The didactic texts are joined by photos of the respective artists, taken by either Roger Manley or Guy Mendes, and emphasize a certain sadness that might otherwise be swallowed by the sterility of a white wall space: these were real people who art history ignored, and who otherwise faced real challenges of health, racism, and poverty. The silver gelatin portraits and the accompanying stories are just as valuable and interesting to see, too. Motifs of alienation followed by adaptation emerge from the biographies of the artists in Where Paradise Lay, making their stories unusually prescient this year.

Three paintings by Mose Tolliver, each titled Self-Portrait, c (1986), are rapidly constructed, and rendered in a manner that is very flattened, colorful, and hybridized with animal-like features. Tolliver’s expressions are of a perpetual surprise or at least fixation. Jonathan Williams, poet and author of Walks to the Paradise Garden, notes that “his house was full of paintings. He paints on everything, with anything. Maybe ten a day.”3 You get the overwhelming sense that the same things were always on Tolliver’s mind—that his fixation with the production of work was the kind of salvation Where Paradise Lay imagines for these artists. Mary Tillman Smith’s work across the room operates in much the same way: intense, quickly generated figurative imagery, this time on the found-object substrate of corrugated metal that originally made up sections of elaborate outdoor collages. The slightly diminutive scale of the figures combined with the colors that rendered them produce something that feels closely related to the nativity lawn ornaments seen around Christmas time. Still, with the sharp, rusty edges of the tin holding these figures up, and with names like Untitled (I am a low man the lord for me) (1984), Tillman’s work calls out with fierce spiritual hunger, much darker than what is conjured by plastic Josephs and Marys in electrified Bethlehems.

Still, to focus too closely on any one thing might miss the forest for the trees. The ultimate effect of a visit is more of a wash of ideas—glimpses of artists we might have known, but never a very clear sense of who they really were, or if they ever found the things they were looking for. Moreover, most of the artists like those in Where Paradise Lay say something large with their cumulative and unrelenting effort of smaller statements across a whole lifetime, rather than with a larger, singular work. In that aspect alone, the format of a group show is somewhat imperfect for these artists, but it is nonetheless unlikely you would see their work presented any other way in the near future.

Where Paradise Lay accomplishes what it primarily sets out to do: spatialize the musings of Jonathan Williams, Roger Manley, and Guy Mendes. This is the obvious shortcoming of the show. The featured artists and their stories are certainly worth exhibiting and celebrating—my heart leaps for this kind of work. Instead, the exhibition fails of a more important success due to the narrative thread that has brought these specific artists together: what stood out to, on the face of it, three White men in the ‘80s on road trips through the American South. Where Paradise Lay might have not declared “These were the artists Jonathan Williams found!” It instead could have asked, “Who are these same kinds of artists still alive today, and what would they have to say about it themselves?” or, “What can we, as KMAC Museum, do to begin shifting the power of who controls the history—and the future—of this art?”

The exhibition statement reads, “[Where Paradise Lay] upholds the museum’s dedication to challenging the aesthetic hierarchies of an institutionalized art world that is too often guided by the outmoded values of our hegemonic education and class-based systems in American life.” KMAC, I hear this. And for what it is worth, I even believe the institution—more or less—means it. But part of that work must be challenging those forces within our own structures, not just in exhibition statements. As 2020 continues to unfold, KMAC will be considering applicants for a new executive director, and it might even dream about changes to the mostly White and affluent composition of other positions of power. Artist Joe Light put it this way: “The difference between right and wrong is a hell of a lots”. So while I recommend seeing Where Paradise Lay, I’ll also recommend watching closely to see which other hells KMAC Museum decides to tackle this year.

-

Where Paradise Lay is on view through November 8, 2020. KMAC Museum is located 715 W Main St, Louisville, KY 40202 and is open Wednesday-Saturday, 10a-4p.

Notes:

- 1. Roger Cardinal, Outsider Art (New York: Praeger, 1972).

- 2. Jonathan Williams et al., Walks to the Paradise Garden: a Lowdown Southern Odyssey (Lexington, KY ; New York, NY: Institute 193, 2019).

- 3. Didactic text from Where Paradise Lay, quoted from Walks to the Paradise Garden: a Lowdown Southern Odyssey.

- “Why ‘Outsider Art’ Is a Problematic but Helpful Label”

-

7.10.20

L Autumn Gnadinger

Print and Digital Media Editor for Ruckus

Install of Where Paradise Lay, Art and Southern Sanctuary, at KMAC Museum.

Mose Tolliver, left to right: Self-portrait, c. (1986), Enamel on plywood 34”x24.” Self-portrait, c. (1986), Enamel on panel 24.5”x21.” Self-portrait, c. (1986), Enamel on panel 25”x22.”

Mary Tillman Smith, detail, Untitled (I am a low man the lord for me) (1984), enamel on corrugated metal, 56”x26.”

Install of Where Paradise Lay, Art and Southern Sanctuary, at KMAC Museum.

Joe Light, The Difference Between Right and Wrong is a Hell of a Lots (1988), enamel on plywood, 48”x96.”