ABOVE: Street view of Museum Row.

︎ L Autumn Gnadinger, Louisville

Where do Louisville’s Art Workers Stand?

Thoughts On

L Autumn Gnadinger

“Art workers,” “art-support workers,” or “culture workers,” are each catch-all terms that describe the same general set of professionals. Examples might include art handlers, security guards, or visitor service personnel, but could include anyone involved in running art spaces/experiences that are neither artists nor upper-level administrators like directors or nonprofit board members.

In the summer of 2019, Michelle Millar Fisher, assistant curator of European decorative arts and design at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, released an open-source spreadsheet titled, Arts + All Museums Salary Transparency 2019. The purpose of this informal project was to have museum professionals share information about what they earn for the sake of galvanizing conversation around what Fisher described as “multi-vectored gaps in pay” for art and culture workers. In addition to the thousands of individuals who participated in Fisher’s document, there has also been an influx of reporting on art labor more generally in recent years, both speaking to the growing interest for this kind of inquiry. Despite all of this attention nationally and globally, there has been all but silence about art labor in Louisville. As a growing movement of unionization and skepticism about establishment practices reshapes the field, where will that leave culture workers in here, and elsewhere in the region?

Anna Louie Sussman’s popular Artsy article from 2017, “Can Only Rich Kids Afford to Work in the Art World?”, pointed out that “Many industries across the economy are making active efforts to diversify their workforces...But key segments of the art market are built upon the spending habits, philanthropy, and social networks of the ultra-wealthy.” She goes on to note that young people “aspiring to work [in] art and design are the most likely to receive financial assistance from their parents,” compared to similar groups going into other fields. Addressing issues like this, if not also beginning to correct them, seems to be a particular motivation for the formation of groups like the New Museum Union whose mission statement reads in part: “We believe that fair compensation for all workers throughout the museum is essential to ensuring its diversity: salaries, wages, and benefits at the museum must be sustainable for everyone, regardless of the privileges afforded them by race, class, or gender.”

While there are few (if any) empirical studies or reports for wages and earnings for art workers in the U.S., the informal figures submitted to Art & Museum Transparency’s spreadsheet do substantiate concern for the compensation of entry-level and mid-level positions at art spaces around the country. Institutions like the Whitney Museum of American Art, for example, have dozens of unpaid internships, visitor services roles are as low as $15.00 per hour (the minimum wage in New York City), and other full-time staff roles ranged widely with many submissions in the $28,000-$35,000 per year range. Meanwhile, the top earner at the Whitney makes $1,046,644 annually, which, while shocking is only around half of what the top earner makes at the Museum of Modern Art, and only around a third of what the top earner at the Metropolitan Museum of Art makes annually. Without a more rigid dataset, it’s impossible to make certain claims about what this information means for the state of art labor in America. It does, however, paint a worrisome initial picture of a field that prides itself on the specter of diversity and progressive thinking.

While meaningful speculation and new action about labor in New York can be made, what can be said for art labor here in Louisville? Sadly, not as much. There are a few submissions on the AMT’s spreadsheet from Louisville and the surrounding cities, but the bulk of what can be found is from art centers in the Northeast and West Coast. Of the 10 submissions that do appear from Louisville, several of the entry-level jobs make only $10-13 per hour without benefits, and most of the salaried positions represented hover close to only $30,000, with and without benefits. Considering our city’s own top earner at a museum—then director of the Speed Art Museum—made $333,481 in 2017 (according to tax forms available through ProPublica), these self-reported figures do also seem strikingly low. An anonymous staff member of a Louisville museum corroborated this picture: “I would say most of us live paycheck to paycheck. It’s almost impossible to imagine being able to work in a museum long-term, especially for anyone who wants to buy a home, support a family, or save for the future.”

Sustainable and livable wages impact the kind of representation our institutions are either inclined to pursue or able to handle at all. Low entry wages in the field, therefore, contribute to longstanding deficiencies of diversity, equity, and inclusion—frequently pointed out in citywide initiatives like Imagine Greater Louisville 2020. If we continue to prevent entry-level jobs from being financially sustainable and accessible for people from lower-income backgrounds, the applicant pool for any of our institutions (at any level) will remain largely affluent. Another current art worker in Louisville summed up the situation: “The institutions in Louisville are doing some work in broadening their diversity through the art being shown in the community. Unfortunately, rarely does that diversity go beyond the art itself and extend to the art workers in administration, curators, registrar, or art handlers.”

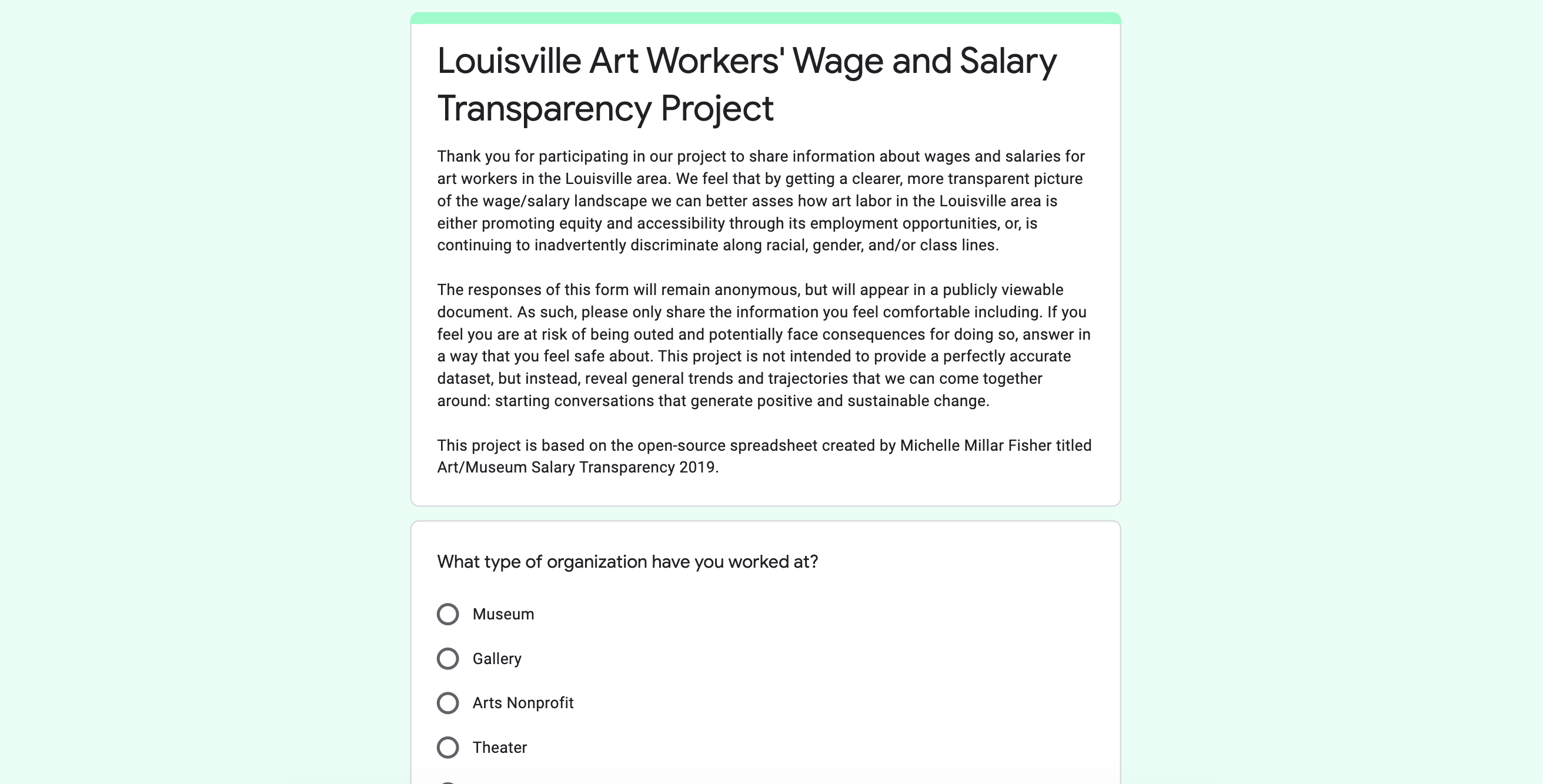

The spreadsheet was opened to global submissions, which introduces many challenges for digesting self-reported information like this. Given each represented city’s different standard of living and livable wage, analysis becomes difficult and actionable steps to improve wages or benefits for art workers become muddied. What would be more helpful is a similar spreadsheet that reflects only the region around Louisville. This way, we can generate a new dataset that can guide further conversation and change that feels appropriate to the region. To this end, I have created a new publicly accessible document, hosted by Ruckus, which will serve as both an archive and a springboard for future assessment. To anonymously contribute information to this document, follow the instructions on this form.

While self-reported measures are imperfect, ultimately, there is no other way at this time to assess wage conditions for art workers in Louisville. The highest-paid earners at our arts nonprofits are easy to find and identify as part of public record. Earnings information on most other positions, however, are not publically available, and the only way to get a sense of where employees stand is to have that information voluntarily shared.

On the subject of wage transparency more broadly, there has been an abundance of writing in the last few years (this recent New York Times piece, for example), which—depending on where you stand—substantiates this as a need and outlines its potential benefits. For one, it can be a potent tool for dismantling things like the well-documented gender wage gap which, in 2018, still puts women’s salaries in the US at 81.6% of that of men’s salaries for similar types of jobs. The thinking goes, that by continuing to keep one’s personal earnings and benefits a secret within a company or organization, there is a risk of continuing to perpetuate ignorance about such discrepancies in earnings.

If we find, predictably, that wages are too low, barriers to entry for people with diverse backgrounds are too high, and our own Louisville-centered art world remains too plutocratic for its own good, what are the solutions? Unionizing is one option, and seems to have recently redistributed power for groups like the New Museum, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Museum of Tolerance (Los Angeles), and the Frye Art Museum (Seattle). But these efforts are risky for its prospective members and do not always succeed. For instance, 28 guides from the PinchukArtCentre were fired just earlier this year after trying to form a union, and historically, it is far from an isolated instance. For many, precarity comes with the job, and a hesitation to cause trouble leads many away from organizing any kind of change. It should be acknowledged then, that just because there is a lack of action, it does not mean there is a lack of interest or need.

It would be impossible to discuss labor conditions for art workers at length and not make mention of the escalating situation in Louisville and its response to the COVID-19 pandemic. At the time of this writing, many of the city’s cultural institutions have been shut down indefinitely (or at least for some weeks), casting an uncertain light on many employees, with contractors and part-time staff most likely to be without healthcare or paid sick leave. While it may take weeks and months to fully realize the impact of this crisis, it matters all the more to talk about the nature of these roles so that they can be made more reliable forms of work.

Art critic Jerry Saltz once described the art world as being “an all-volunteer army,” meaning, that there’s not much room for complaining or for improving working conditions and compensation. At the current moment that might be true. While Saltz and others like him are resolved to placate readers to that reality, the rest of us do not have to be. After all, art workers, more often than not, require specialized training, education, certification, or all three. Whether you are a contract fabricator, an education programming facilitator, or an upper-level administrator, these qualifications cost time and money and should be appropriately compensated within their own contexts.

While writing and criticism about visual art generally benefit from sequestration from other adjacent public humanities—theatre, music, dance, etc—and vice versa, the challenges faced by these kinds of organizations and their employees are more similar than they are different. Transparency, therefore, is only mutually beneficial to learning more about the current state of our city’s art workers, and how to move forward addressing these concerns. If you consider yourself a part of this larger ecosystem, employed by an arts organization either regularly or as a contractor, you are invited to participate. Our cooperation here might be the beginning of a more sustainable, diverse, and equitable arts workforce in the city.

-

Notes:

- Contribute to the Louisville Art Workers Wage Transparency Spreadsheet.

- To see previously contributed information.

L Autumn Gnadinger

Print & Digital Content Editor, Contributor

3.14.20

Street view of the Speed Art Museum.

Screenshot of the new submission form for a Louisville-specific wage transparency spreadsheet.

Street view of the Kentucky Center for the Arts.